Interview with emeritus Professor Robinson Hollister

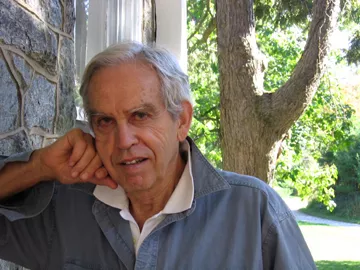

Emeritus Professor Robinson Hollister

Rob Hollister was a distinguished professor of economics at Swarthmore College for more than 40 years, from 1971 until his retirement in 2015. He balanced his time at Swarthmore with a successful career in public policy work. Hollister was a leader in his field, and a pioneer in the use of random assignment studies with his work on the New Jersey Negative Income Tax as part of the Economic Development Office’s War on Poverty. The random assignment study (often referred to as a randomized controlled trial or RCT) has since become a standard tool in applied economics --- the recipients of the 2019 Nobel Prize in Economics used it extensively in their research. In the spring of 2020, Eleanor Miller (Swarthmore ’22) interviewed Professor Hollister about the trajectory of his long career in economics. Below is the lightly edited transcript from her interview.

Miller: How did you initially become interested in the field of economics?

Hollister: When I was in high school, I used to go to the library all the time in the summer. [One summer] the biggest newspaper in New Jersey, The Newark News, had an essay contest. I had become interested in public policy, in particular agricultural policy, so I submitted an essay to this contest on agricultural subsidies. Now this was a pretty unlikely subject for a high school kid which probably contributed to me winning the prize for the best essay. I guess writing that essay got me going in the economics realm, which I continued as my major at Amherst College.

Miller: Is that one of the reasons you ended up choosing to attend Amherst?

Hollister: No, actually I chose Amherst because I was a huge swimmer and it had the best swimming pool in New England. I came to Amherst as an undeclared major and actually wanted to try to study English literature because the English literature department at Amherst was the best in the country, but I guess I didn’t make the cut for that subject. So I focused on economics and really found myself excelling, and I decided to continue pursuing it at Stanford.

Miller: Did you go directly from Amherst to Stanford?

Hollister: No, after I graduated from Amherst, my first job was at Deerfield Academy, a well-known private high school nearby in Massachusetts. I taught there for a year. When I went there, I was really interested in teaching English literature. When I got there they said, “Oh, well, we had to change things around, you’re going to be teaching geometry.” So I did that for a year. However, I got a notice from my draft board that my number was coming up, and this was [a time of serious Cold War tensions], so there was real concern that if I got drafted, I would get sent to a conflict zone. I found out however, that there was an option called the National Guard where you go for the first six months of active duty training, and after that you had to go to a local meeting every week but could otherwise remain living a civilian life. I took that option and went to Fort Dix in New Jersey for military training. While at Fort Dix I learned that I had gotten into Stanford, so I went there in the fall.

Miller: What was your experience like at Stanford?

Hollister: Stanford had a fabulous economics department, so I was definitely able to learn a lot. I was also able to take some English classes, and I really enjoyed that opportunity. While I was at Stanford, I decided to pursue a Fulbright in England. That was really my first exposure to economics applied to public policy. I had a mentor who was a young professor at Oxford. At some point he decided to go to the US and marry his American girlfriend, and he offered me his apartment in London under the condition that I write a draft paper for a study he was doing for the Prime Minister. The paper was a success. A little later, my mentor was asked to start up a unit on the economics of education for the United Nations Cultural Institution in Paris. He had too much on his plate at the time, so he sent me instead. So, there I was in Paris working to head up this unit on education. Then, about three months later, this same mentor asked me to write another paper, this time for the International Labor Office in Geneva. I wrote this paper, which really kick started my international career in public policy and economics. After that I just kept going with the flow and ended up having these incredible opportunities all around the world. I was able to travel and work in over 40 countries throughout my career.

Hollister became involved in evaluating the OECD’s (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) Mediterranean Regional Project which was a major educational planning effort involving countries such as Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Turkey, and Yugoslavia.

Miller: It seems like you had a successful career abroad. What made you decide to come back to the United States and become a professor at Williams College?

Hollister: I was working in London for my Fulbright when my father died. I decided I had to come back to the US and try to enter the economics job market. I interviewed at a bunch of schools, and I got offers from Yale and from Williams. I chose Williams primarily because I had been an undergraduate at Amherst, which was Williams’ rival and a very similar school. I figured I would be happier in the small school setting.

Miller: What was your experience teaching there as your first academic job? What classes did you teach?

Hollister: When I was there, I taught three different courses. Everyone in the economics department at Williams had to teach the basic Introduction to Economics course. Additionally, I taught Microeconomics, which was something I had done as a graduate student at Stanford so it seemed natural for me. Finally, I taught Developmental Economics, which focused on countries that were not very advanced economically. I enjoyed this because it was a relatively new, hot field at the time. Also, Williams had a special program at the time that brought in civil servants from developing countries to train them in economics.

Miller: After being at Williams you went to work as part of the “War on Poverty” at the Office of Economic Opportunity. What was it like working for the Poverty Program?

Hollister: The Poverty Program had just been created, and I went there as a researcher. I was there for about 6 months when I was asked to head the research division. Around this time, President Lyndon Johnson passed a bill in Congress which mandated that every division of the federal government write a plan describing their objectives and how they were going to meet these objectives. At the Poverty Program, one of our main objectives was to reform the welfare system. This was where we had the idea of using random assignment studies. [In the social sciences] a large-scale random assignment had not been done before; it had been done only on small scales. We decided [to employ this methodology in an assessment of] the Negative Income Tax project in New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

The Negative Income Tax (NIT) has long been proposed as an alternative or supplement to traditional anti-poverty programs. The NIT transfers cash assistance to households with incomes below a specified threshold. The amount of assistance phases out as the household’s income rises. One of the major questions about the NIT is whether it would reduce work incentives among recipients. The NIT experimental study was designed to assess the extent to which the NIT would have this effect.

Miller: How did you determine that a random assignment was the proper method for this study?

Hollister: With the Negative Income Tax program, we were considering creating a new [anti-poverty] program for the federal government. The question was how to properly evaluate [a pilot version of] this program. Normally, that was simple, you run the experiment and take a look at the results. But in this program the objective was to measure the work effort of the families that got the negative income tax grant. That it is difficult to measure using traditional statistical methods. We had determined the population we wanted to study, families receiving the cash grants under the Negative Income Tax. But you had to have a comparison group, and that is when we decided to use random assignment. The families getting the grants and the families in the comparison group would be, on average, exactly the same composition except for the fact that some were receiving the grants and some were not. Using random assignment allowed us to compare the two otherwise identical groups and isolate the impact the grant had [on work incentives], so that is why we used that method.

Miller: And was the random assignment experiment successful?

Hollister: [The random assignment methodology] was proclaimed to be a success by people in Washington, and people began to imitate it. We (the Poverty Program) subsequently participated in several other such experiments. Then other divisions of the government started implementing random assignment experiments and it became the thing to do.

The success of the random assignment methodology led Hollister to help design and conduct experimental public policy studies around the country. These projects took place in Indiana, Iowa, North Carolina, Washington, Colorado and Wisconsin among others. In a move back to academics, Hollister became a faculty member in the Department of Economics at the University of Wisconsin from 1966-1970. He then came to Swarthmore College in 1971.

Miller: Why did you decide to transition to working at Swarthmore College?

Hollister: That’s a good question. When I had been at Stanford, there was a fellow [Lewis Gaty] there who had been an undergraduate at Swarthmore and then returned to the College as a professor after Stanford. He left the College on a sabbatical leave and asked me to fill in for him. I accepted and we [my family] went off to Swarthmore. But that was only a temporary job. When it was over, I went back to working on the New Jersey NIT project, which had an office in Princeton. While working on the project, I taught in the Woodrow Wilson School at Princeton University, but I ended up coming back to Swarthmore when that project had concluded.

Miller: Throughout your career you were consistently switching and/or working simultaneously in the fields of academia and public policy. What did you enjoy about that crossover? Was it ever difficult to switch back and forth?

Hollister: None of it was difficult, and I enjoyed most of it. The experience was always very interesting ---going to all these cities, looking at these different organizations, examining different kinds of questions, using quantitative methods. I just kept getting invited to do something else and I always found it enjoyable and interesting, so I had no reason to stop.

For this part of the interview we were joined by current Swarthmore Professor of Economics, John Caskey, who had worked with Hollister on an assessment of a Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) in the Mississippi Delta between 1995-2004.

Miller: What inspired you to start working on the CDFI assessment?

Hollister: It started because of other consulting work. In particular I had done some consulting work with the Pew Foundation in Philadelphia. Pew had made a grant to an organization in the Mississippi Delta to help develop local firms, especially firms headed by blacks or women. Pew had appreciated the work I had already done with them and asked me to help with this project.

Caskey: This project was very interesting as it had three parts to it, but I’ll describe two of them. One was a newly created not-for profit “bank” that could provide financing to help businesses in the Mississippi Delta, especially locally-owned firms that were not involved in agriculture, to expand and create new job opportunities in the region. The second part of the initiative was a job training component called the Workforce Alliance. The idea was that the bank would provide the firms with financing and technical assistance. The businesses would start expanding and employing people and this job training program would train people to get the jobs with these businesses. Our (Hollister and Caskey) job was to evaluate the success of this initiative.

Miller: You decided not to use a random assignment to evaluate this study, why was that?

Hollister: As I recall, the study didn’t lend itself to the random assignment design because it had so many actors in it. It would have been difficult to really implement it effectively.

Caskey: I clearly remember Rob thinking about how to evaluate this. He decided that we couldn’t do a random assignment because it was a community-wide development effort. You could not say we’re going to do this in 100 communities and not in these other 100 communities and then sit back and watch them over time and see what happens. What Rob did, which I found very interesting to watch, was to educate them (Pew) about what could realistically be done in terms of an evaluation so they would have reasonable expectations. Rob warned Pew that one could not look at raw data, say 20,000 jobs added in the Delta, and assume that the intervention had anything to do with that. There were so many other factors, such as the end of a recession or shifts in demand across industrial sectors, that affect employment in a region and have nothing to do with your intervention.

Hollister: That became part of my toolkit. When I went around to places, I was always saying, ‘Look, the first thing is do not over promise on what you can do in terms of evaluation. Just be realistic and then deliver.’

Miller: What was the outcome of the project? Was this regional development strategy generally successful?

Caskey: Yes, but not in the way the project was initially envisioned. The initial project design was simplistic and flawed. But the loan fund that was started as a result of this project still exists today. That is because of some very committed people in Mississippi who, when something didn’t work out, kept trying different ideas. So they ended up making something out of the loan fund that was never initially envisioned. The fund has now become a large credit union that has offices throughout the Delta and provides financial assistance and banking services to low income people and regional businesses.

Miller: When have you found random assignment studies to be most effective? What are their limitations; when can you not use them?

Hollister (jokingly): We don’t ask ourselves that because everything we touch is successful.

Caskey: Rob has written papers noting that random assignment studies won’t work for assessments of community initiatives. In these cases, the evaluation has to be more observational and judgmental. I think random assignment is most effective when one can create a clear control group and experimental group and observe and measure the differences between those two groups over time.

Miller: Shifting gears a little, describe your research work with Swarthmore students. What did you most enjoy about working with them?

Hollister: Well, they were very competent. I’ve had several young students come work with me and we ended up publishing articles together. They were all great students, and some are now working as professors at Columbia, NYU, Princeton, University of Chicago, Berkeley, etc.

Caskey: I’ll say this; an awful lot of Swarthmore students got their first job after college because of Rob. Rob has done plenty of consulting work over the years and he used that as a pipeline for a lot of Swarthmore students. Over the years, hundreds of Swarthmore students walked into Rob’s office and said, “You know, I’m graduating and need a job” and Rob would pick up the phone and get them a job at Mathematica or the Urban Institute or a number of other places in economics or public policy work.

Miller: What advice would you give to an economics student at Swarthmore?

Hollister: I think what I would say is to think seriously about a career in public policy because you can really make a big contribution. I think, particularly now, there is a huge void in the field of public policy. The Trump Administration has fired or driven out so many capable people and really emptied out key parts of the administration. I think, when his term is over, there is going to be an opportunity to start something new and make a real impact.

Miller: Why did you decide to stay at Swarthmore for 40 plus years?

Hollister: The major element I would say, was that the students were so good. In fact, we (the faculty) had a saying that the first rule was to do no harm. We didn’t want to mess too much with the students and get them off track because they were good enough already. Another reason for staying at Swarthmore were my colleagues in the economic department. There was one guy in particular, Bernie Saffran, who was quite the character and really my best friend at Swarthmore. Another big factor was the sabbatical. At most colleges, you teach for 7 years and get a one-year sabbatical. But at Swarthmore you teach for 3 years and get a sabbatical. That meant I got freed up much more frequently to go work on all these projects.

Miller: Out of everything you accomplished in your career, is there any study or experiment that you are most proud of?

Hollister: It would have to be the New Jersey Negative Income Tax. It was part of the Poverty Program, which I felt was an important and impactful program. And it certainly had a lot of adventure to it. It also started me on this long career of combining economics and public policy work.