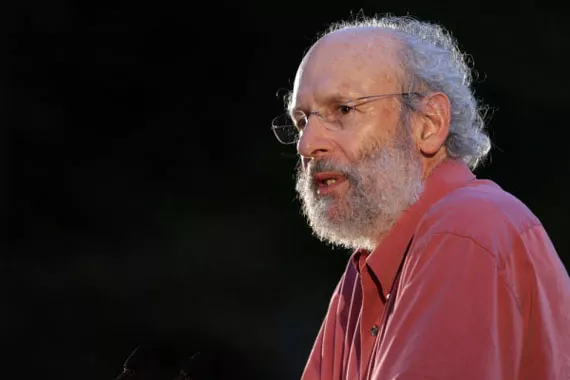

Kenneth Sharpe: Last Collection

Audio Transcript

Swarthmore 101: "On Bringing Out the Good in Others"

Being asked by the Class of 2012 to speak on the eve of your commencement weekend warms my heart. That is because being taught by you and teaching you makes me flourish. Eudaimonia - Happiness - Aristotle called it. So it is an honor to be here.

You know that giving lectures is not the way I teach. I would much prefer to be sitting and dialoguing with you. Until the early morning hours. But I'm hoping to make some observations that will encourage you to reflect and dialogue with each other. I want to observe something most of you already know. And more importantly do. It is something that Swarthmore helps encourage. But next week, the world you walk into will actively discourage it. Unless you do something about it.

This something is the bringing out of the good in each other. It's not something you talk about a lot. When you talk about "doing good," you usually talk about doing good for the world; doing good for others less fortunate than you. Despite the pressing concerns of getting into graduate programs and getting jobs and making enough to live on, you're committed to preserving the air we breathe and the water we drink and preventing the ravages of rising temperatures. To fostering social and economic justice. To creating better urban schools and more equitable work places. To protecting the rights of minorities, of immigrants, of gays and lesbians.

But in talking about doing good for others you talk less abut this other thing you practice daily: helping to bring out the good in your friends and classmates - and sometimes even in your teachers.

How should we approach this subject? Well - this being Swarthmore - we could design a course: "On Bringing Out the Good in Others." Somebody is bound to take it - after all, where else would anyone sign up for a course on "Greed," or "Creativity in Economics," or "Writing Revenge," or "Subverting Verses," or the "Meaning of Life," or, for that matter, "Practical Wisdom"?

Swarthmore 101: The Course

So what would it look like? First we would have to establish that there was a good in others that could be brought out. Then we would have to look at the institutional arrangements that might do the trick.

We could start by giving credence to the opposite position. General George C. Marshall Jr., most well known today as Truman's Secretary of State and author of the Marshall Plan, captured this in his reflections on the brutal treatment of Filipino civilians by American troops in the early 1900s. He told a fellow officer, "Once an army is involved in a war, there is a beast in every fighting man which begins tugging at its chains." We saw that beast come out in My Lai in Vietnam, and more recently in places like Abu Ghraib in Iraq. Philosopher Thomas Hobbes knew that beast well. The natural state of man, he wrote in his book Leviathan, is a state of war. The desire for gain and glory and power, coupled with radical personal insecurity - psychological as well as physical - create distrust, uncertainty, and a logic to be the first to attack. Violent competition - not cooperation - is our human nature. And this makes necessary strong, authoritarian political institutions: rules, laws, and fear of punishment were the chains to restrain the beast.

We could then look at what Hobbes missed: the beauty that sits beside the beast in man. The dove, the angel, the kinder soul, the cooperative spirit, the compassionate being: it, too, is often chained, discouraged from flourishing by the very system of punishments and external rewards that the heirs to Hobbes have designed to tame the beast.

That would then raise the question: can institutions be built not simply to contain the darkness that lurks in the heart of every man, but to bring out the light? Yes, said philosophers like Aristotle, Rousseau, Tocqueville, and John Stuart Mill. Human nature, they argued, contained both possibilities. It was the task of our social and political institutions to bring out the good in man while restraining the evil. And that's what good statesmen try to do. My long time friend and colleague Doug Bennett (until recently president of Earlham) argues that this is exactly what statesmen like Washington, Madison, Benjamin Rush, and Jefferson were trying to do when they founded the U.S. Constitution on the republican tradition initiated by Aristotle. Yes: interests had to check interests. But they also wanted to create institutions that "extracted virtue from people" instead of extracting Hobbesian self-interest. They set up political institutions to encourage public reflection and deliberation; they believed that if people were forced to publicly defend their ideas, and do so in terms of universal ideas and principles, this very process would create the possibility for people to bring out their better selves. The possibility: it doesn't always work.

We could then turn to what modern science and social science teach us. On the one hand we have the work of ethologists who claim, from their studies of primates, that aggression is an essential part of the nature of the animals from whom we descend - particularly males. Ethologists like Franz de Waal make this picture more complex: common chimpanzees do demonstrate aggression and scheming in power struggles - he compares these to human politicians, but bonobos (the small, pygmy chimps) are capable of empathy, kindness, compassion, patience, and reconciliation. We have the research in neuroscience that Patricia Churchland talked to us about last year: how evolution and natural selection didn't simply create an aggressive struggle for survival - didn't simply prepare us for "fight or flight" - but also encouraged the development of neuro receptors and neurochemicals in the brain, like the peptide oxytocin. These give us pleasure in caring for our offspring and, eventually, for our kith and kin. Compounds like oxytocin ground our capacity for empathy and care.

In psychology, we could look at the rich field of "moral development." This research educates for character and wisdom - and what discourages it. We now have some scientific backing for Aristotle's ancient claim that people by nature were meant to be social animals, with the logos - the speech and reason - that enabled them to discourse about ethics, social animals who become fully human in and through others, whose passions and emotions can be educated into an emotional intelligence that is an ally - not an enemy - of reason. We know that people can learn to love their friends and families; that people have the potential for loyalty and commitment to their communities; they have the potential to be fair and just; to be caring; to be patient; to be good listeners; to be empathetic. These capabilities are just as innate as greed, selfishness, the lust for gain, the desire to dominate.

Finally, I think, we would need to look at which capabilities are encouraged by which institutions. For example, we would need to look at how regimes shape character - both the dark side and the bright side. Aristotle's arguments that bad regimes - tyrannies and oligarchies and unrestrained democracies - corrupt the character of the citizenry. Marx's arguments (in his early writings) that capitalism alienates human beings from each other - and from their real selves. We could turn to historical cases. We could look at how fascist and authoritarian regimes encouraged the routine exercise of inhuman acts. Or, less dramatically, we could look at how a legal system in the United States, which fails to restrict the impact of wealth in politics and campaigning, helps encourage vitriol in politics. We could look at the institutions that encouraged the hatred of blacks and gays and lesbians in the U.S.; we could look at the effects that apartheid in South Africa and brutal military regimes in Central America had on their people. But then there is the flip side: the positive effects of the new institutions built in the aftermath of the civil rights movement, of the anti-apartheid struggles, of Latin America's civil wars; the effects of the new institutions now being built by gay and lesbian supporters. We can look at how these structures can slowly, often very slowly, encourage the beginnings of reconciliation, of decency, of tolerance and respect. We could invite in my colleague Keith Reeves to talk about what kinds of rehabilitation programs in prisons can help bring out the good in people; he and about a dozen Swarthmore students just came out of a term in prison - an academic term that is - where they joined a group of inmates who took the same class. We can ask everyone in that class about bringing out the good in Swarthmore students and prisoners alike.

And then: we could take a short break for snack...

Swarthmore 101: The Real Course

This would be a great course to teach, but right now, you - and your friends and family, and my father, Irwin, who is joining us tonight - don't need such a course. Life experiences have already taught you the central point: that it is both possible and urgent to bring out the good in other people.

How do we parents know the importance of bringing out the good in others? Because it is what we have been trying to do for years. Child rearing is not simply pushing you to get good grades so you can get a good college pedigree and a good job. It is also about bringing out the best in you. And this turns out to be a very tricky thing to do. It is tricky because the best in you may not be what was best in us, or the best in our other children. It is tricky because it demands knowing when and how to be angry; when and how to listen; when to talk, and when we've said enough. It's tricky to teach you how to ride a bike because it demands knowing when and how to let go. It's tricky teaching you how to deal with pain and failure because the temptation is to try to prevent it from happening. But preventing you from falling off the bike will discourage you from learning grit, self-confidence, and courage. And what makes all this even trickier is that we parents start out with little or no experience - until we make mistakes and you teach us.

You know yourselves the importance of bringing out the good in others because of your life experiences. You do it all the time with your best friends. In fact, what you and your best friends have going is a kind of mutual mentoring. You learn from and teach each other. You learn how to be responsible and trustworthy and loyal: to be there to advise and console over the breakup even though you have an exam the next day; to help her figure out an assignment even though you don't know how you're going to get through your own. You learn when and how to listen and be empathetic - even when you can't believe he really did that -because you've figured out that being good friends demands understanding how the other thinks and feels. You learn these things the way we parents to: by getting them wrong. You stumble. You reflect. You learn. Trial and error. Will Roger's famously said: "The way you learn good judgment is experience. And most of that experience is bad judgment."

Your experience being a student at Swarthmore has also taught you the importance of bringing out the good in other students. Why? Because it's part of what makes your classes and organizations and dorm life work. Think of the pre-writing sessions some of you have with your roommates or classmates: sitting around the first floor of the library or some lounge or some floor giving each other feedback, challenging each other's arguments. What does it take to have discussions like this? Not just raw academic knowledge, but patience and care; an ability to be open and to open up; the skill and will to balance criticism and support. Tearing apart and helping put back together. Your experiences in the classroom have taught you that you can't have the dialogue you want if a handful of students are monopolizing the conversation; if they are not inquisitive about what you think, concerned about why you are confused or silent.

Those of you who have been Resident Assistants or Writing Associates or Student Academic Mentors know from your experiences the importance of bringing out the good in others. You encourage the students in your care to be more reflective - to recognize their strengths weaknesses. To think about others before they blast music at 2 a.m. To be brave enough to confront personal conflicts. Courageous enough to write a paper in a new way.

So without any course "on bringing out the good in others," your experiences and mine have taught us the importance of bringing out the capacities we all have for empathy, caring, good listening, loyalty, courage, humility, grit, reflectiveness, and love. We don't do this because there is an Eleventh Commandment "Thou Shalt Bring Out the Good in Others." We do it because it is necessary to do this in order to have friends, in order to learn as students, in order to be a successful parent or teacher.

Institutional Design and System Builders: the Hidden Secret

It would be nice, on the eve of your graduation, to say: "now go forth and continue to bring out the good in others." But, alas, it is not going to be easy. That's because the institutional environment that we often take for granted at Swarthmore will not be there. Worse, the institutions that you work in may actively discourage you from nurturing the good in yourselves and others.

It is not that your work places will force you to do bad things - although that may happen. In fact, many of you will work for organizations that aim to do some good. But there is still a danger that these institutions will try to control your behavior using external rules and incentives - and these rules and incentives may inadvertently start squeezing the good out of you and your colleagues. Unless you do something about it.

There are lots of psychology experiments which show this effect. James Heyman and Dan Ariely had group of college students pose with a moving van parked near a busy sidewalk on which they placed a big couch. The students asked passersby for assistance putting it in. Most were willing to help. Then they changed the scenario: they offered to pay a small fee to passersby to help them load the couch. Far fewer were willing. Why? What was first construed as a social transaction - doing a favor - was reframed as a market transaction and the passersby thought about the size of the fee, not how to be helpful. Of course, there was a price which would make it worth their while to load the couch but the fact is that the very incentivizing of the activity changed its moral meaning.

That was a experimental situation. But there are real cases, like the Israeli day care center that was having a problem with the parents. A handful of parents were frequently coming late to pick up their kids and that meant the day care providers couldn't close up and go home. So the administrators came up with a brilliant idea: let's fine the tardy parents for each lateness. So how did it work? Not so well: more parents failed to show up on time. What happened? The fine for doing wrong changed the activity into a market transaction: being late had a price, and if you were willing to pay that price, then why not? Responsibility to the children's caretakers? Consideration that they too had lives? A sense of fairness and decency? All undermined. The incentives didn't bring out the best in the parents; it demoralized their relationship with the care providers. When the school realized its mistake six months later, it abandoned the fines. And what happened? Parent lateness increased yet again. Now lateness was free.

We can find examples of this close to home. Writing Associates at Swarthmore - better known as WAs - have long been paid a stipend for the term, not an hourly wage. Nobody thought much about that piece of the institutional structure until the College, for complicated reasons, changed the system of payment to an hourly wage. The effect on many of the WAs was dramatic. Previously, most of them had only roughly calculated the hours spent with the student peers they tutored. What was supposed to be a half hour session might extend longer if they felt a student needed more help. Sure: the stipend for the semester was useful, but it was not their central aim. Mentoring was. But the new system encouraged them to think about their work as a job, not a vocation; the hours they put in began to become a central concern. Conflicts arose that never existed before: if a Writing Associate had a 45 minute conference with a student instead of the standard 30 minutes should she be paid more? If she spent more time, would she be accused of needlessly padding her hours? And how about the mentoring that the WAs gave each other: were they to keep track of the time spent helping each other and charge for that? Notice that no one who changed the system had given a second thought to how monetizing the hours worked would transform the commitment and caring that the system had been encouraging in the WAs - the good it was bringing out of them. But there it was: a small change in something that no one even thought about turned out to be an important part of the program's institutional design. Luckily all was not lost: This being Swarthmore, the WAs quickly recognized what this new system was doing to them and their commitments. They talked with the faculty, who then worked with the administration to craft an innovate alternative which largely restored the best of the old system. The story had a happy ending because people were willing act to preserve the design of an institution that was bringing out the best in the WAs.

But the story could have ended differently. And in the years to come, you will have many chances to write the endings to such stories.

How hard will it be to write good endings? Hard, but often not impossible. In fact, the research that Barry Schwartz and I have done about institution builders and designers - statesmen Aristotle might have called them - demonstrates that small but important advances are often made by people who do not think of themselves as statesmen or system builders, let alone as heroic or special. They're just doin' what needs to be done.

* * * * * * * *

Why was history teacher Susan Szachowicz spending hours every Saturday in 1999 meeting with a handful of her fellow teachers at Brockton High School in Massachusetts? Because the school was an educational disaster zone. Because a quarter of the students were unable to pass statewide exams. Because the state was threatening to block the graduation of 750 students a year. And because the state would likely impose a standard solution that would prevent Szachowicz and her colleagues from helping the students flourish: a lock-step, highly scripted curriculum, backed by a set of monthly tests. Teachers call it "drill and kill."

But what would be a better alternative for their 4100 students - 64% of whom were quite poor; two thirds of whom were black and Hispanic; and included Pakistanis, Brazilians, Haitians, Asians, Cape Verdeans, Africans, Guatemalans? The most important skills to teach, they decided, were reading, writing, speaking, and reasoning. Drill and kill wouldn't do it. Their plan was a required writing program in every class - math, science, even gym.

They came up with their own rubric for teaching writing - one that made sense for their students and for their teachers and for each subject matter. They then convinced the other teachers that this would work. They met great reluctance: How do we teach writing in science and math and gym? Let us help you said the Committee. They organized teachers into small groups and started training. They knew that they could bring out the best in their colleagues and in their students and this gave them the passion and energy and commitment to do all this work.

When the first state test scores came in (Spring 2001) they rose sharply. This galvanized the dubious teachers. Scores of them signed on. By 2009 and 2010 Brockton High was outperforming 90 percent of Massachusetts high schools - and all without a lockstep, highly scripted, "drill and kill" curriculum.

* * * * * *

In a courtroom in Buffalo, Gary Pettengill stepped before Judge Russell. "Hi, Gary," said the Judge. "Nice to see you, and why not give me an update."

"My family and I moved into a new home," said Mr. Pettengill.

"That's good news," said the judge. "How do you like it?"

"It's pretty nice," said Pettengill. "Different neighborhood. Pretty quiet. A lot bigger, though, than before. More room for the kids to play inside."

Why is a judge having this conversation with a drug offender like Pettengill? That's because Judge Russell is a judge in a special court, a veteran's court. It's a court that aims to balance retribution and rehabilitation - which is what criminal justice is supposed to be about.

Pettengill was a 23-year-old veteran who had planned to make the army a career until a severe back injury in Iraq forced him to take a medical discharge. Married, a third kid on the way, Pettengill suffered from post traumatic stress disorder and nightmares and started using marijuana to ease the symptoms. Only able to get part-time work because of his back, unable to put food on the table or buy baby formula at $21 a can, he started selling marijuana, too. He was busted in a drug sweep. A New York Judge, in a normal court, following the normal mandatory sentencing requirements, would have had to sentence Gary Pettengill to serious prison time as a drug felon. Pettengill's family would have been kicked out of their apartment and the welfare system might have taken his kids away from him.

But Pettengill was in a veterans court. The first of its kind in the U.S. A court that Judge Russell had designed. To build the new system, he got support of local prosecutors, the Veterans Administration, social workers, other vets. All of them agreed: non-violent offenders like Pettengill shouldn't be thrown into prison because they didn't have the work to support their families and get medical assistance. That would resolve nothing: they would just revolve in and out of prison for the rest of their lives. To prevent such revolving door justice, all agreed with Judge Russell: they needed a court that could both punish and bring out the good. Russell's court became a national model - 22 other cities created such courts by late 2009. And the 108 vets who had completed the program in Russell's court by February 2010, the number who came back through the revolving door? Zero.

* * * * * *

Why is Michael Morse, a third-year Harvard medical student (and Swarthmore '03), trying to figure out how to help Alex lower his blood sugar levels? Alex is a diabetic who lives at a men's residence hall in the poorest area of Cambridge. His dosage of insulin is not bringing down his levels, and Michael is trying to figure out what do. But most other third-year med students across the country are not learning medicine by carefully following patients like Alex. Instead, they are following more senior residents and attending physicians around busy hospital wards, simply watching doctors who pepper them with tough questions. Doctors who model a brisk technical efficiency. Doctors who present the patients as helpful teaching cases. Doctors who spend little time at the bedside and less time doing a follow-up. Michael, too, spends time doing such rounds, but he spends every morning working in a clinic where he has a one-to-one and year-long-relationship with a doctor. After Michael finishes his examination of Alex, internist Pieter Cohen, who has been mentoring Michael every Monday, joins them. Michael repeats to Dr. Cohen the diagnosis he has given Alex and the treatment plan he is recommending. Dr. Cohen signs off or makes revisions. Later, they sit down and review the session. The issues Michael faces are complex: not simply figuring out the correct insulin level, but how to get Alex to change his behavior, to stop eating the free doughnuts and cookies that are always lying around his men's residence. To do this, Michael needs more than technical skills; he needs to learn how to understand what Alex is thinking and feeling. He needs to learn how to balance this empathy with detachment. He needs to learn how to listen. He needs to learn how to gain Alex's trust and how to be patient. Michael knows the value of patient choice and autonomy, but he needs to temper this with the need to nudge Alex toward changing his behavior, toward choosing the right thing.

Now, the reason that Michael is learning these things - and most other third year medical students aren't - is not just because Michael is a Swarthmore grad; and its not just because Dr. Cohen is a fantastic mentor and role model. It is because they are both part of a relatively new program at the Cambridge Health Alliance Hospital, a local community hospital. It was designed specifically to develop the good character traits that doctors need - not just their scientific knowledge and technical skills. And the two Harvard medical school doctors that designed this program - Drs. Dave Hirsh and Barbara Ogur - designed it exactly because the standard institutional design was discouraging exactly the good qualities that doctors needed. For example, their research, confirmed by similar studies, showed a decline in empathy among medical students after their third year. And that was particularly troubling because it is the third year that the students leave their academic classrooms and begin to do hands on care in hospital wards. The first- and second-year students were highly empathetic, highly motivated to care, so how could their actual contact with patients corrode this? And why did the erosion of empathy continue in later years of medical school? Ogur and Hirsh figured out that it was the very structure of the standard training - the bad mentoring by busy residents and physicians in hospital wards who had to examine patients quickly, would only see them once or twice, had little time to talk to them - and less to talk with the third-year students. So Ogur and Hirsh designed a new program. It put students like Michael into clinics each morning with doctors who would mentor them for the whole year. It assigned each student 15 patients for whom they would be responsible for the whole year. The result? The students ability and motivation to be empathetic increased - and they did at least as well on their medical boards as the other third-year students.

Conclusion

Few people set out after graduation with the life goal of bringing out the good in others. Nor should you. But achieving your life goals will demand you pay some attention to this. Just like you paid attention to it at Swarthmore: bringing out the good in order for you be a real friend and to have friends, to love and be loved, to surround yourselves with the kind of students that enabled you to be a good student.

The administrators and deans and staff and faculty at Swarthmore have worked with you to sustain an institutional environment which encourages you to be the kind of people you are. But you can't take this kind of institutional design for granted after you walk off this podium with your diplomas on Sunday. The "real world," as many of you call it, will urge you to sweep aside concerns about developing character and practical wisdom as quaint, unscientific, unrealistic, impractical. The well-oiled machinery of modern organization abhors the uncertainties and dangers of learning through trial and error. Giving you discretion to exercise judgment will often be considered dangerous and unreliable in a world where the primary concern of managers is figuring out how to control your behavior with smart rules and incentives.

But it doesn't have to be this way. Institutions can be designed to help bring out the good in those that work in them. That's one of the hidden secrets you have learned at Swarthmore.

People can be motivated by the real aims of doctoring, of teaching, of judging, of policing, of banking, of law, of politics - instead of relying on external incentives like money or glory or power. People can be given the discretion to learn wisdom through trial and error, and reflection. Mentors and coaches can model what good practice looks like and show novices how to be fair-minded as well as merciful, courageous as well as humble, empathetic as well as detached.

But for that to happen, all of us need to be soul crafters, designers, and protectors of institutions which enable the good in others to flourish. And ultimately, that's what will enable us to flourish too.

Thank you.