Student Projects

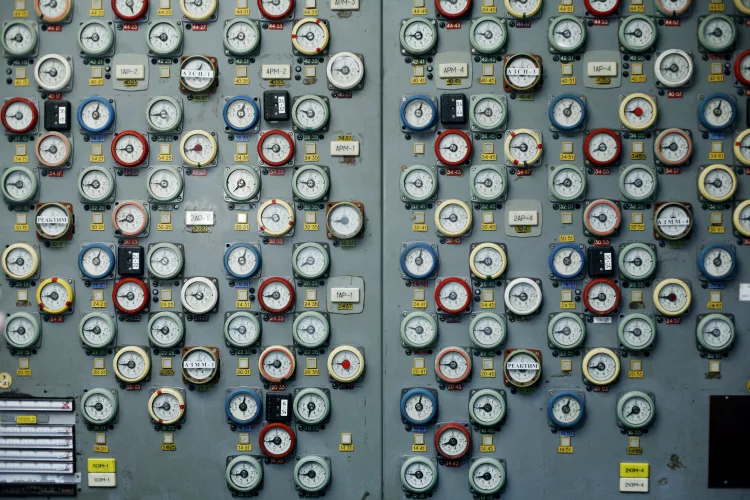

Chernobyl: Nuclear Narratives and the Environment

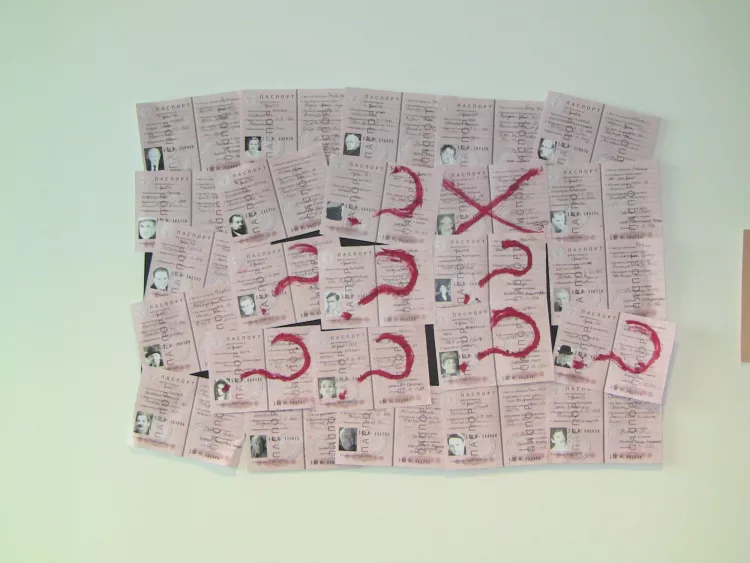

Crime or Punishment: Russian Narratives of Captivity and Incarceration Story Map

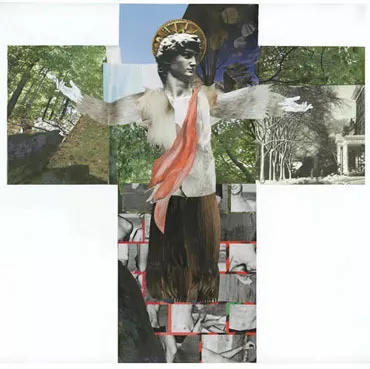

Rachel Lee's Interpretive Dostoevsky collage

Found Poems in Russian Prison Literature

_________________

The Reactor Room is a digital installation featuring the work of students in Professor José Vergara’s course Chernobyl: Nuclear Narratives and the Environment (Spring 2020) at Swarthmore College. This interactive exhibition seeks to facilitate public engagement with the Chernobyl catastrophe and its associated mythology.

_________________

As part of our efforts to understand the collection of texts that makes up Russia’s long tradition of prison narratives, students in Swarthmore College's Russian 037: Narratives of Incarceration and Captivity have designed this StoryMap. We hope that this project will allow readers to understand this tradition through both space and time.

Russian writers have responded to the experience of incarceration in multifarious ways. Alexander Solzhenitsyn, for example, viewed his time in the Gulag labor camps as an ultimately positive experience, going so far as to “bless prison for being in [his] life.” Others, such as Varlam Shalamov, would go on to describe the depravities of prison life in harrowing detail, while simultaneously maintaining that neither writers nor readers should concern themselves with such overwhelmingly negative tales.

The Nobel Prize-winning poet Joseph Brodsky once wrote, “A prison or concentration camp is society’s extension.” With its broad historical perspective, this course in turn illuminated numerous aspects of Russian culture through an examination of its prisons, of its narratives of individual and collective captivity, and of related social conflicts from the medieval ages to the post-Soviet era.

With the exception of some editorial revisions, all commentary on this page has been produced by students in RUSS037 (Spring 2019). They were tasked with selecting one text from the syllabus and one to be read on their own. Click on the map on each slide to zoom in.

For more information, please contact José Vergara (jvergar1@swarthmore.edu).

_________________

_________________

Beards, Braids and Beatings. The final project for Russian Fairy Tales, Spring 2010. Students were tasked with creating skits around their favorite Russian Fairy Tales using different story telling props, and then performing them live in accordance with oral tradition.

_________________

Bulgakov Museum. The final project for Bulgakov, Spring 2011. Each student prepared an exhibit highlighting a certain aspect of Bulgakov's worldview as put forth in his plays and novels. Exhibits highlighted fanciful items such as Margarita's flight over Moscow and the ubiquity of gourmet food, as well as the more sinister, such as missing persons and an overcrowded morgue.

_________________

Chekhov in the Courtyard. As the culminating project of a course on Revolutionary Theatre (Spring 2013), students gave a live reading of two of Chekhov's early farces, The Bear and The Proposal, in the Cosby Courtyard.

_________________

Rachel Lee

RUSS 21

Johnson

5-13-10

Analysis of Interpretive Project

I had originally planned to create both Rogozhin's and Myshkin's crosses in the style of Russian icons, but decided to make one large cross instead. This large cross would better illustrate the ways in which Myshkin and Rogozhin combine to form the original ‘perfectly beautiful human being' that Dostoevsky envisioned.

The cross is divided horizontally and vertically, into what could be called Rogozhin and Myshkin territories. The lower half of the cross displays the brickwork of black-and-white bodies with green and red ‘mortars' visible through the cracks. The fragmentation of bodies ties back to Dostoevsky's descriptions of Nastasya. The orderliness of the brickwork pattern refers to Rogozhin's ability to scheme and calculate. Beneath this orderly façade, lies the suggestion of an unquenchable, fiery passion, his physical desire for Nastasya. The small amount of green visible between the bricks alludes to another of Rogozhin's greed, his desire to possess everything he wants.

The upper half of the cross, Myshkin territory, represents the spiritual half of the Dostoevsky's original idea. In this portion of the cross, there is a noticeable lack of artifice and of people. Myshkin cares deeply for the suffering of others. The emotional connections he establishes with those around him, along with the inexplicable attraction that others feel toward him, cast Myshkin as more of a spiritual than a secular being. Movement up the cross shows the transition from the passionate Rogozhin half of the cross, to nature scenes and then finally to the images of the sky that crowd around Christ's head. These images of heaven appear to rest on Christ's shoulders and concentrate around his halo.

This curious portrayal of Christ merits explanation. His head is the head of Michelangelo's David, reportedly the most beautiful man ever to have lived. The positioning of his hands is not the customary placement. They express longing, not suffering, and seem to beckon to something the spectator is unable to see. The richness of Christ's garments connect him to Rogozhin, while his slight build alludes to Myshkin's body, which at first sight indicates that he suffers from falling sickness. The small red toga lying across Christ's chest again refers to Rogozhin's passionate nature. What appears to be a skirt is intended to be the lower half of a robe, much like the robes the figures in religious icons wear. This robe is constructed from human hair, making it all the more expensive and bizarre.

Finally, the stones at the two left bottom corners serve as counterpoints to the direction in which Christ is looking. They demonstrate the opposition between the weight of sin and lightness of God's good graces. Christ looks away from the stones, which resonates with the novel's conclusion. Prince Christ could not endure the world. Thus the world will have lost its savior.