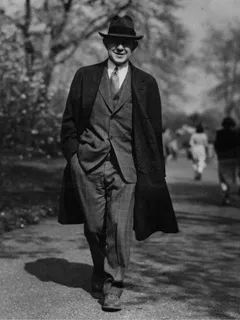

Frank Aydelotte

1921–1940

Frank Aydelotte's nearly 20-year tenure as president is best remembered for the Honors Program he introduced in 1922. At its inception, it provided an experience that was otherwise unknown in American undergraduate education: a rigorous intellectual experience in which qualified upperclassmen studied subjects in small groups, without grades, for two years until evaluated by outside scholars in a series of written and oral examinations.

Aydelotte (1880–1956) had benefited from similar training as one of the first Rhodes Scholars. Believing that the Oxford University honors system could be applied to a small college in the U.S., he saw Swarthmore as the perfect place to do so. The program’s success was due in large part to his emphasis on raising the intellectual level of the College as a whole—hiring faculty who were experts in their field, reducing the student-faculty ratio, and making admission to the College more competitive. His cooperative administrative style and the mutual respect he shared with the faculty were also critical to his success in implementing such sweeping curricular changes.

The Honors Program brought increased expenses for the College, but the national attention it received was more than sufficient to bring in grants and donations. The General Education Board (GEB) was a particularly strong supporter, seeing Swarthmore as a “sponsored laboratory.” According to the GEB, “The Swarthmore experiment has already had a perceptible influence in raising the standard and ideals of undergraduate work in the country at large.” Over the years, the details of the program have been revised many times, but the core features of the program have remained unchanged since President Aydelotte first introduced it, including the focus on independent learning, absence of grades, and external examinations.

Aydelotte also foresaw the benefits that would result from close interaction and joint research projects between faculty and students, decades before it was a key feature of the country’s top undergraduate science programs. In 1927, he brought the Bartol Research Foundation to campus with the expectation that a “great research laboratory” would further add to the College’s “intellectual life.” Although the relationship between Bartol and Swarthmore ended in 1977, for 50 years Bartol scientists employed Swarthmore students in various capacities, taught classes at the College, and collaborated with faculty members.

In addition to the curriculum, Aydelotte also brought significant changes to the more social aspects of campus life. He gradually de-emphasized the role of football on campus, shifted responsibility of the College’s athletics program from the alumni to the administration, and added the coaching staff to the faculty. Aydelotte also banned fraternity hazing and reduced the number of fraternity dances. To the dismay of many alumnae at the time, Aydelotte also supported the women students’ decision to disband all sororities.

In 1939, Aydelotte left Swarthmore to become the second director of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, which he helped to found. He maintained his commitment to the Rhodes Scholar Program, which he administered from 1917 to 1953. Aydelotte also joined the Board of Managers in 1945 and became a member of the Joint Anglo-American Commission on Palestine. The year after his retirement, the College’s faculty anonymously published the tribute An Adventure in Education: Swarthmore College Under Frank Aydelotte, which described the successful “experiment” that was the Honors Program.