Assessing Peace Studies

A Framework for the Swarthmore College Department of Peace and Conflict Studies

Figure 1. Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS) is an interplay between research, education, and action.

What is Peace and Conflict Studies?

- An fully-transnational, centuries-old applied field of inquiry that attempts to understand, mitigate, and ultimately prevent large-scale violent conflict.

- An interdisciplinary field representing diverse perspectives on power, justice, and the causes of conflicts. Our department aspires to actively cultivate links with many areas of the arts, humanities, and social sciences, as well as engineering and other STEM fields.

- A dynamic interplay between research, education, and action (Figure 1) in which the findings of research influence action, often through education; while what happens in action sets the new agenda for research and education.

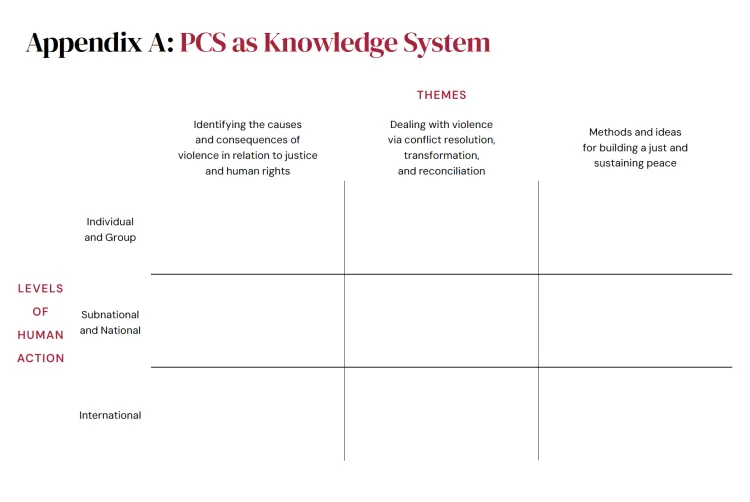

- A knowledge system (Appendix A) that organizes the activities of research, education, and action by themes of concern and levels of human action.

- A systematic inquiry into multiple modalities of violence, including:

- Direct violence: overt, physical violence of perpetrators and victims.

- Structural violence: in which unjust social institutions and practices deny certain groups the ability to meet a variety of their basic human needs.

- Cultural violence: the deeply ingrained attitudes, norms, symbols, and practices that legitimize direct and structural violence.

- Dynamically interactive with historical injustices and ongoing, complex problems of society that often generate or correlate with violence.

- Intentionally normative and transparent in its baseline values: conflict is natural to the human experience, but violence need not be integral to human interactions for dealing with conflict.

- Continually engaged with contested rationales and various ethical quandaries that legitimize violence as an acceptable political or social means for handling conflicts.

- Diverse, as manifest by the names operative in the 100+ programs in U.S. Colleges and Universities: Peace and Conflict Studies, Peace and Justice Studies, Institute for International Peace Studies, Peace and Global Studies, Program on the Analysis and Resolution of Conflicts (PARC).

- At the academic and pedagogical crossroads of significant trends and contending perspectives of U.S. higher education regarding:

- an inward, self-critical interrogation of the field’s complicity with imperialism and white supremacy;

- expanding understandings of violence, resistance, and nonviolence;

- deconstructing and decolonizing a once standard knowledge hierarchy;

- addressing issues of identity, class, race, and gender as discrete yet interlocking systems of oppression underpinned by global capitalism and settler colonialism.

What are the shared epistemologies of peace scholars and researchers?

- Consideration of violence as inherent or natural to human behavior in debate with violence as learned and legitimated. Anthropology, sociobiology, psychology, education, and now neuroscience engage these issues.

- Theories, ethics, strategies, and outcomes of non-violence. Includes several disciplines ranging from personal philosophies and agency, through organized collective non-violence, and now empirical studies of campaigns of strategic civil resistance against corrupt regimes and dictators.

- Theories, ethics, strategies, and outcomes of organized group violence operating with a national government as target. Social science study of rebellion, revolution, civil war, terrorism, and more recently the political economy of militia violence.

- Considerations of how “outsider” and “insider” actors develop enduring peace after periods of large-scale violence/war.

- Peace as authentic in “human security,” defined by empirically measuring the life experience of citizens in their society following their reintegration into a working social, political and economic system that sustains peace among former enemies.

- Conceptualizing and testing conditions for practical, critical, and radical forms of peace.

- Considerations of the transnational norms and institutions existent and yet required to create sustainable peace.

- Consideration of the links between peace and justice in theory and practice. This entails drawing connections across human rights, transitional justice, reparative justice, restorative justice, redistribution, and reconciliation, while intentionally casting a wide net to avoid reproducing Eurocentric and liberal systems of knowledge and power.

- “Epistemologies of resistance” employs philosophical perspectives to highlight the connections between knowledge social injustice. It argues for an intersectional view that emphasizes consideration of race, class, and gender.

- The contemporary and fast-moving epistemological crises of disruptive information technologies, disinformation, and the emergence of AI as they relate to peace research, the competing knowledge bases accessed by students in peace studies courses, and praxis/policy advocacy work in the field.

What are the shared approaches to pedagogy of peace studies teachers and educators?

- Engaging in classroom discussions, assignments and activities that reflect the meeting ground of peace pedagogy and critical learning theory.

- Creating practical and experiential opportunities for students and faculty to engage with particular issues both at home and abroad, mirroring the relationship sketched in Figure 1.

- Teaching the varied dimensions of non-violence—from the development of a personal position on violence through the histories of applied non-violent direct actions, to the more recent social justice and civil resistance campaigns (e.g., through their participation in the Global Nonviolent Action Database).

- Training to provide conflict analysis skills, followed by building competencies in conflict resolution techniques and strategies of conflict transformation.

- Training to develop—through critical inquiry, background research, and empathetic listening to conflicting parties—opportunities for conflict transformation and the building of a new relationship between the parties, in preparation for a full peacebuilding plan.

- Providing varied experiences and learning opportunities to study, observe, and facilitate the three key strategies of conflict transformation that comprise the TAS system:

- Transactional changes: maximizing the insider-outsider linkages that our era permits us for peacebuilding within our communities and beyond our locale.

- Attitudinal changes: influencing leaders, relational and identity-based groups, education and religious organizations to change the way they see the “other.”

- Structural changes: creating the new institutions, policies, and big patterns of communal life that help the transformation of violence to durable peace.

- Greater engagement with groups or ideas that are marginalized by the absence of a peace paradigm that considers race, class, and gender.

- Cultivating “The Moral Imagination”. This involves reading Lederach’s book of the same title, and then examines a real-world justice crisis or an intractable conflict in group-based exercises.

- Declaring peace education as the new citizen education of our era.

- Utilizing the Pathways to Peacebuilding Wheel as a deeper dive into career opportunities.i Our department has internalized a few central principles that have fundamentally shaped our alumni, such as the notion of “radical humanization.”

PCS as Knowledge System. Themes and Levels of Human Action