Pioneering Women

In keeping with the tenets of their Quaker faith, Swarthmore's founders established the College as coeducational since its founding in 1864. Equality also intentionally extended to the governance of the school, where the Board of Managers consisted of an equal number of women and men. When it was discovered in 1870 that Pennsylvania law did not allow women to serve on boards, the group successfully petitioned state legislators to change the law so that women could legally continue to serve.

Featured below are some of the dedicated women who have influenced the College through the years.

Lucretia Mott

Swarthmore College founder Lucretia Mott (1793-1880), a Quaker minister and major figure in the reform movements of the 19th century, devoted her life to the abolition of slavery, women’s rights, school and prison reforms, temperance, peace, and religious tolerance. Her home in Philadelphia was a stop on the Underground Railroad and her support of women’s education also led to the founding of what became the Medical College of Pennsylvania and Moore College of Art, both in Philadelphia.

Swarthmore College was created out of a desire by Mott and other members of the liberal Hicksite branch of the Religious Society of Friends to establish a place “under the care of Friends, at which an education may be obtained equal to that of the best institutions of learning in our country.” Today, her papers, including personal correspondence, sermons, essays, anti-slavery documents, and the diary of her trip in which she led a delegation of women to the World Anti-Slavery Convention of 1840 in London, can be found in Swarthmore’s Friends Historical Library. Mott is profiled in the documentary series The Women of Philadelphia.

Martha Ellicott Tyson

(1795-1873), an abolitionist, supporter of women's rights, and elder of the Hicksite Quaker Meeting of Baltimore, had a long-standing concern for Quaker education. It was at her home in Baltimore, Md., in 1860 that a group of Quakers decided it was time to begin the campaign that would lead to the creation of Swarthmore College. When she wrote for the Friends Intelligencer about the need for a new school, she rhetorically asked how many Friends, who might have been “bright and shining lights,” had passed their days “so obscured by ignorance” that their talents were lost to the world.

Upon her death in 1873, Baltimore Yearly Meeting published a memorial of her life that included the tribute: "The improvement and development of all our faculties, and a higher standard of education in our Society, was a subject which for many years deeply interested her mind. Recognizing our responsibility to our Heavenly Father for the right use of all His gifts, and believing the cultivation of our intellectual powers renders us more useful to each other, 'in bearing one another's burdens,' and this 'fulfilling the law of Christ;' she earnestly advocated this view on all suitable occasions... The interest awakened by her and a few concerned Friends in this particular, originated the movement which culminated in the establishment of Swarthmore College."

Susan Cunningham

In 1869, Susan Cunningham (1842-1921) became one of the founders of the mathematics and astronomy departments at Swarthmore, and she headed both divisions until her retirement in 1906. At the time of her retirement, she was the only faculty member who had been at the College since its beginning. In 1888, she was awarded Swarthmore’s first honorary degree. She later became one of the first six women to be elected a member of what is now the American Mathematical Society, where she remained a member until her death. Additionally, Cunningham planned and equipped the first observatory at Swarthmore, where she lived until her retirement. Today, Cunningham House is home to the Scott Arboretum.

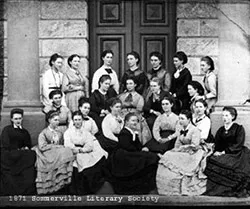

Somerville Literary Society

Barred from joining the two campus literary societies for men, members of a women’s baseball team organized their own society and opened it to all Swarthmore women students and alumnae in 1871. They chose as their namesake Mary Fairfax Somerville (1780-1872), a Quaker and an accomplished scientific writer from Scotland who supported women’s education. The purposes of the organization were to discuss literature, to strengthen the friendship between its members, and to prepare them for “the wider field of action and influence opening to women,” according to their constitution.

Members published a magazine until 1910, sponsored speakers, and raised money to award graduate fellowships named for College founders Lucretia Mott and Martha F. Tyson. They remained active on campus through the 1940s. As more women graduated, the organization grew into an ad hoc alumnae association. By the mid-20th century, the organization was primarily for Somerville alumnae and concentrated its efforts on managing the fellowships, which are still awarded today. Their records at Friends Historical Library includes their constitution, minutes, financial papers, writing, correspondence, and material concerning the Lucretia Mott and Martha F. Tyson Scholarships.

Helen Magill White, Class of 1873

As women were an integral part of the founding of Swarthmore College, so too were they equally regarded as students. Co-education, the opportunity for women to engage in college work as equals as men, was unusual and still controversial at the time of Swarthmore’s inception. "Nothing short of co-equal, co-educational advantages, and the same degrees conferred upon both sexes for equal attainments, will meet the demands of the times," wrote Edward Hicks Magill, who served as Swarthmore's president from 1872-1889. "The time will come when our posterity will read with amazement and incredulity the statement that in the City of Philadelphia, after the middle of the 19th century, the question was seriously entertained by a dignified and intelligent body of educators, in advance of their age in many things, whether women were intellectually equal to men and whether the sexes should be educated together in our higher institutions of learning."

His daughter Helen Magill (1853-1944) was a member of the first graduating class of Swarthmore College, which was comprised of five women and one man. Magill went on to earn a Ph.D. in Greek from Boston College, becoming the first woman to earn a doctorate degree in the United States. She worked as an academic and educator.

Somerville Hall

Funds to build a gymnasium for women came in large part from Mary Stevenson Wistar, who served as Swarthmore’s director of physical culture from 1893 to 1894. She was so dismayed at the lack of proper facilities for women that she returned to Swarthmore her year’s salary to start a fund for a gymnasium. Built in 1893 with additional support from the Somerville Society, the building served as a women's gym and housed gymnastics equipment on the first floor with dressing rooms, lockers, and showers on the lower level. In 1912, with a gift from Philip Sharples, a building housing the women's swimming pool was added and connected by a corridor to Somerville Hall. The building was located where McCabe Library, built in 1967, now stands. In 1981, almost a century after Hall Gym's construction, John and Marian Snyder Ware ’38 donated money to build Ware Pool. Marian was captain of the women’s swim team and wanted to give future students a chance to enjoy swimming as much as she did.

Alice Paul '05

A New Jersey Quaker and pioneer in non-violent resistance, Alice Paul (1885-1977), Class of 1905, was the leader of the militant wing of the suffrage movement from 1913 to 1920. She founded the National Woman’s Party and organized pickets of Woodrow Wilson’s White House for women’s suffrage. Later, she wrote the first version of the Equal Rights Amendment submitted to Congress.

Paul’s Swarthmore connections predated her arrival on campus. Her grandfather, William Parry, shared a spade with fellow College founder Lucretia Mott to break ground for the planting of the first trees on campus. Her mother, Tacie Parry, was in the College’s first class of students in 1878 but left before graduating when she got married.

An effort to open a women's center on campus culminated in 1975; students named their new space in Bond Hall for Alice Paul. In the next decade, the center grew in popularity, moved to larger accommodations in a former fraternity house, and even hosted some of the events held during the College's two-week celebration of the 100th anniversary of Paul's birth. In the early 1990s, the center was renamed the Women's Resource Center. In 2005, Paul's name returned to campus on an award-winning residence hall.

Jane Addams

Jane Addams (1860-1935) is recognized as one of the most prominent reformers of the Progressive Era as well as the founder of the social work profession in the United States. She was a peace activist who co-founded the Women’s Peace Party, which later became the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF). In 1931, she became the first American woman to be award the Nobel Peace Prize.

Addams had strong ties to Swarthmore. She had been invited to speak in 1918, when her popularity was at an all-time low because of her opposition to WWI. In 1930, Addams donated her papers to the College, establishing the College's Peace Collection. The next year, Swarthmore awarded Addams an honorary doctorate, the same year she became the first American woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize. In 1932, she attended the College's Founders Day and planted a tree on campus with President Frank Aydelotte, commemorating the 250th anniversary of William Penn’s landing in Pennsylvania.

Her collection at Swarthmore includes her Nobel prize medal.

Ellen Starr Brinton & the Swarthmore Peace Collection

The Swarthmore College Peace Collection (SCPC) was established as a research library and archives in 1930 when Jane Addams donated her books and papers related to peace and social justice to Swarthmore College. The Women’s Peace Party, later called the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF), also began depositing its files at the same time. From these two collections, the SCPC has grown to encompass the papers of many individuals and organizations, reflecting the spread of the peace movement in the United States and around the world. Over half of the Peace Collection documents the prominent role played by women in the peace movement.

Ellen Starr Brinton (1886-1954), Quaker, feminist, and internationalist, served as the first curator of the Peace Collection, from 1935 until her retirement in 1951. In this role, she established collection and arrangement policies for the WILPF papers and other material. Her various historical interests initiated several collections such as the peace seals and stamps and covers collection and the material pertaining to Benjamin West's painting "William Penn's Treaty With the Indians."

Before and after World War II, Brinton traveled to Europe to secure valuable peace records. During her 1937 trip to Europe, she correctly assessed the growing political turmoil, especially in Germany, where she spent time with peace activists. During this trip she also met Rosa Kulka, a member of the Czechoslovakian WILPF. Brinton's attempts to assist Kulka, her sister, and two nieces escape Nazi-occupied Europe are documented in her papers, now archived in the Peace Collection. The Brinton collection also includes personal correspondence, travel journals, address books, notes, manuscripts, and typescripts of articles. After her retirement, Brinton was one of the founders of a venture to promote interracial understanding which became the Media Fellowship House.

Odetta

Folk music legend Odetta headlined the student-organized Swarthmore Folk Festival in 1958. Past featured performers included Leadbelly in 1946, Woody Guthrie in 1949, and Pete Seeger in 1953. The festivals were held from 1945-1967 in the spring and equally featured folk singing and folk dancing.

In 1996, Odetta returned to the College to perform during the celebration of Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. That appearance generated a mutual interest between Odetta and members of the Music and Dance Department to arrange for her to become a visiting professor of music. Her class the next year, Music as Social History, blended folk music and discussion on how the genre makes connections among diverse peoples and societies.

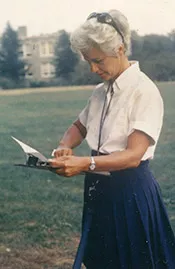

Eleanor Kay "Pete" Hess

Professor Emerita of Physical Education Eleanor Kay “Pete” Hess (1924–2011) was a fierce advocate for women’s athletics at a time when women were not provided the same opportunities as men in college sports. During her 33-year career as an administrator, Hess chaired the Department of Physical Education and Athletics for Women from 1965 to 1979, and then served as the associate chair for the Department of Physical Education and Athletics from 1979 to her retirement in 1990. As a coach, Hess guided four different sports at Swarthmore: field hockey, women’s lacrosse, badminton, and tennis. She led the lacrosse team to 121 victories, second most in program history, and led the field hockey program to 140 victories, the most by any coach in program history.

She was inducted into the Pennsylvania Lacrosse Hall of Fame in 2000 and the National Lacrosse Hall of Fame in 2002. She also served as president and treasurer of the Philadelphia Women’s Lacrosse Association.

In 2012, she was inducted into the Swarthmore Athletics Hall of Fame. In her honor, the Eleanor Hess Award is given to the sophomore woman who demonstrates a love of athletics, leadership, hard work, fairness, and objectivity.

Kathryn Morgan

In 1970, Sara Lawrence Lightfoot Professor Emerita of History Kathryn Morgan (1919-2010) became the first African American professor hired by Swarthmore as well as the College’s first folklorist. For more than 20 years, Morgan not only taught courses in history and black studies, but served as a pioneering scholar and mentor to countless students and colleagues. Despite early tensions in her department and an initial denial of tenure, Morgan became the first African American woman to receive tenure at the College. In 1991, Morgan was the first recipient of an award created by the College’s black alumni and named in honor of her contributions to the lives of African Americans at the College. In 2000, a scholarship was established in her name to support students with an interest in black studies. In 2003, in collaboration with Professor of Studio Art Syd Carpenter, who provided illustrations, her book of poetry Envisions was published. In 2009, she listened beaming, as students, faculty, and staff members read her poems at the inaugural Kathryn Morgan Poetry Festival.

Women's Resource Center

Seeing themselves as part of feminism's "second wave" and inspired by the organizing efforts of African American students in establishing the Black Cultural Center, members of Swarthmore Women's Liberation began pushing for a place of their own in the early 1970s. Their efforts were successful and in spring 1974, the College established a women's center in two rooms on Bond's second floor. Papers concerning the founding of the center are archived in Friends Historical Library.

Shortly after, the center came under attack, as chronicled by the many Phoenix editorials and articles about the bitter fights over funding between the center and the Student Budget Committee. Because of the controversy, the center's members thought naming it for a prominent alumna would help bring legitimacy to the young organization.

At a Dec. 5, 1975, dedication ceremony, the center was named for Alice Paul, Class of 1905 and a lifelong advocate for women's rights. Paul, 90 years old and living in New Jersey, was invited. Although unable to attend, she was reportedly very pleased by the news.

In the next decade, the center grew in popularity, moved to larger accommodations in a former fraternity house, increased its library of women's studies texts, and added paid interns. In 1985, the center even hosted some of the events held during the College's two-week celebration of the 100th anniversary of Paul's birth. But the name didn't last; in the early 1990s amid student debate about how to broaden the center's appeal and the role it should play on campus, Paul's name was quietly dropped and the center was renamed the Women's Resource Center.

Rebecca Chopp

Rebecca Chopp served as the 14th and first female president of Swarthmore College. As president, she promoted the "signatures" of the College—academic rigor and creativity and intentional, residential community—in order to affirm and amplify the College's tradition as a progressive leader in liberal arts education in the nation and the world. She also upheld the College's longstanding commitment to admitting the most highly qualified students without regard for their financial circumstances.

In addition to weathering the global recession of 2009 without reducing faculty, staff, or financial aid, Chopp also oversaw Swarthmore's first strategic planning process. The establishment of the Frank Aydelotte Foundation for the Advancement of the Liberal Arts is one tangible expression of the resulting plan; another is the creation of the College's first campus master plan.

Chopp is a well-known scholar of progressive religious movements in American culture and has also focused her research on changing structures and cultures of higher education and the role of liberal arts in a democratic society. She is the author or editor of six books, including Remaking College: Innovation and the Liberal Arts (2013).

Valerie Smith

, a distinguished scholar of African-American literature and culture, became the 15th president of Swarthmore College on July 1, 2015. She is the first African-American and second woman to hold the office of president at the College. She also holds tenured appointments in English Literature and Black Studies.

As president, Smith has placed a strong emphasis on ensuring that Swarthmore continues to focus its efforts on access and opportunity, diversity and inclusion, and sustainability. She has also worked to build and strengthen relationships between the College and the region and around the world.

Smith received her B.A. cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa from Bates College and her M.A. and Ph.D. from the University of Virginia. She is the author of more than 40 articles and three books on African-American literature, culture, film, and photography and is the editor or co-editor of seven volumes. Her most recent publications include Toni Morrison: Writing the Moral Imagination; The Norton Anthology of African American Literature (Third edition), edited with Henry Louis Gates Jr.; and Race and Real Estate, edited with Adrienne Brown (Oxford University Press).

Martha Ellicott Tyson

Martha Ellicott Tyson Valerie Smith

Valerie Smith