Away They Go!

Rows of graduates, relaxed and smiling; black gowns splashed with the vivid colors of roses; the cooling movement of a Japanese fan.

ALTHOUGH HOT AND HUMID, THE WEATHER WAS HARDLY AN ISSUE on the last Sunday in May when a winding black line of gown-clad seniors processed into the Scott Amphitheater on the final leg of their Swarthmore journey. Swarthmore’s 139th Commencement was under way. In a setting whose natural beauty never fails to amaze, parents, siblings, and other relatives witnessed a rite of passage that is timeless in its ability to move and excite, as their children, still seniors, ascended the rocky steps on one side of the stage, then descended a few moments later on the other side as graduates.

Fanning themselves with their programs, family members applauded and cheered proudly and often raucously as President Rebecca Chopp handed out diplomas to 366 graduates, of whom 358 received Bachelor of Arts degrees and 14 Bachelor of Science in engineering degrees. Six graduates received both.

Preceding the awarding of diplomas, Chopp presented honorary degrees to publisher and philanthropist David Bradley ’75, criminologist David Kennedy ’80, and entrepreneur and educator Iqbal Quadir ’81. Senior class members chose Natalie Bamdad, an honors English literature and psychology major, as their class speaker.

The day before, Isaac H. Clothier Professor of History and International Relations Robert DuPlessis and Howard A. Schneiderman Professor of Biology Scott Gilbert delivered the Baccalaureate and Last Collection speeches, respectively.

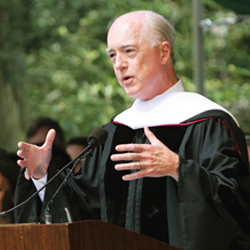

Swarthmore College President Rebecca Chopp

REBECCA CHOPP

Swarthmore passion is, in my experience, unique. Passion, in the world at large, is often about pursuing a “personal thing” and, for this reason, passion can allow emotions to govern reason (something, by the way, that our Quaker founders would find abhorrent). But Swarthmore passion, so honed by critical thinking, is almost always guided by the demands and needs of the world in all its many dimensions, whether it is to figure out a particular problem in math, to design a program to improve the lives of impoverished women and children, or to sculpt a new expression of beauty. “To find your mission in life,” author Frederic Buechner is quoted as saying, “is to discover the intersection between your heart’s deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger.” Swarthmore passion, it seems to me, is always the incredible combination of your heart’s gladness and the world’s great need.

And the world needs you, desperately. Class of 2011, as you leave this magnificent amphitheater and all that you have known and loved so well during the past four years, please carry with you your greatest discoveries, your most profound understandings, your remarkable creations, and your deepest connections. Fix your full attention to truth, beauty, goodness. May you find yourselves fueled by Swarthmore passion.

May your heart’s gladness fit our world’s needs.

NATALIE BAMDAD ’11

I keep returning to this memory from freshman year: It was after winter break and my parents were dropping me off at the bus station. As they were leaving, I said offhandedly, “Bye, I’ll call you when I get home.” And I thought, “Home? Is Swarthmore home now?” Many of us probably have some version of this story, a memory of that strange moment when you realize you now have two homes, rather than just one.

I began today by saying that there is no singular Swarthmore-graduate experience, and there isn’t. However, what makes right now so special and important is that today, in this moment, 366 uniquely different people are all looking in the same direction.

So with that in mind let’s get out there and embark on new journeys, sow seeds of intellectual curiosity, erect towers of innovative thought, and do other vaguely imperialist sounding things to make Swarthmore proud.

David Bradley, publisher and philanthropist

DAVID BRADLEY ’75

My first week at Swarthmore, I sat at a carrel in McCabe Library, trying to absorb the semester reading list for a political theory seminar. I remember tears of frustration, maybe anger, at the workload. A woman from the seminar stopped to talk: “You’re the transfer student, aren’t you?” I explained my fear that I couldn’t do all the reading on the semester syllabus. She said, “‘Semester syllabus?’ That’s this week’s reading list.’

Therein began Swarthmore’s gift to me: the invitation to enter—and eventually the confidence to occupy—the life of the mind.

The change in me that year was like a physical crossing. My mental frame was as if you could think and think and eventually hit a wall where the insights stopped. Then, Swarthmore would demand you think further. Suddenly you discover that that terminal wall is porous. And, thinking harder, you cross over—or through—and find a whole new space of original ideas. Most students crossed over more easily than I. But those moments where I did cross were transporting. They were foundational to the companies my wife and I built, and central to the privilege I’ve felt in owning The Atlantic.”

For 36 years, I’ve been grateful to Swarthmore. Now, the Board and President Chopp bring me this honor. I didn’t know I could be more grateful. But, like that first week in political theory seminar, you took me to a deeper place. I find therein nothing but gratitude.

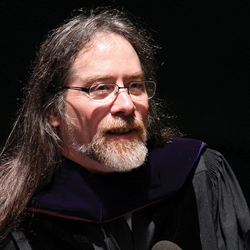

David Kennedy, criminologist

DAVID KENNEDY ’80

The morality I was raised in was one that said act responsibly, do your best, and you will have no one either to answer to or to apologize to. Do any less and you are violating your obligations to yourself as a responsible person, an adult, a citizen. I’ve come to believe that that is a pretty good gloss on what a liberal arts education—particularly at Swarthmore—seeks to produce. Over 30 years ago, I sat where you are, delighted and relieved to be graduating, with no idea of what to do with myself. A few years later, I stood in one of the worst crack markets in Los Angeles—in a professional capacity, I hasten to add—and saw the devastation around me and thought, we have to do something about this. Thirty hard years later, we have figured out what to do about the worst of the violence, fear, and racial tension that saturate America’s most distressed and oppressed communities. That path has been travelled by a growing community of extraordinary people refusing to accept that those problems could not be solved, willing to think in unexpected and often deeply unpopular ways, and honoring equally clear thinking and effective action. That community is saving lives, restoring neighborhoods, and dissolving racial animosity all over the United States.

Those habits of mind, the fundamental orientation bred into me personally at home and honed here at Swarthmore College, are central to why we have been able to make our way.

Iqbal Quadir, entrepreneur and educator

IQBAL QUADIR ’81

In addition to my formal education here, Swarthmore gave me two important things:

One, knowing that I am part of a special group of people gave me much-needed confidence in myself, allowing me to take risks, break out of the mold, and work on social problems in what might be called new ways.

Two, Swarthmore gave me a sense of community and a sense of purpose: that, whatever I do, I need to work toward improving society—exerting a tremendous influence on making me an entrepreneur determined to bring telecommunications to Bangladesh.

Entrepreneurship, you ask? Indeed, sometimes, people think of entrepreneurs as those driven to make money. This is not true.

In 1911, Joseph Schumpeter came up with the fundamental economic theory on entrepreneurship. He was in his late 20s at that time, one reason I have such faith in young people. Even to this day, Schumpeter’s The Theory of Economic Development is still the essential thesis on this phenomenon.

His point was that entrepreneurs are not necessarily driven to make money but rather to make change. They break out of the mold to innovate and to make their mark.

Swarthmore students have the confidence, the intellect, and the imagination to move away from the conventional. They are risk-takers and mold-breakers. Seen in this light, entrepreneurship is, at its heart, very much the Swarthmore way.

Mortar boards disguised as flower arrangements, all against the soft greens of the Scott Amphitheater—Swarthmore’s 139th Commencement provides a stunning show.

Friends forever.

Email This Page

Email This Page