Quakers and Slavery

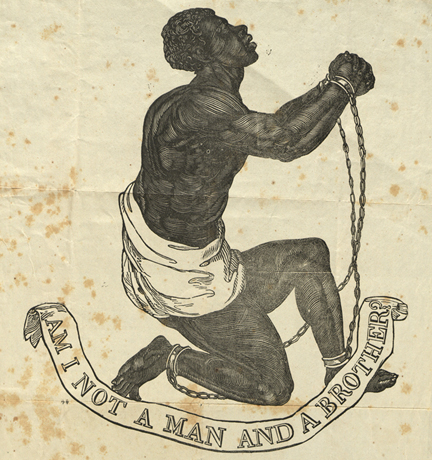

This 1835 depiction of a slave in shackles—which served as the heading of a broadside on which appeared John Greenleaf Whittier's poem "My Countrymen in Chains!"—was one of the items included on the collaborative website compiled from artifacts housed in Haverford College’s Quaker Collection and Swarthmore College’s Friends Historical Library.

In November 2010, Swarthmore College with the support of the Cooper Foundation, hosted one day of the international conference “Quakers and Slavery.” The event was held over three days, with one day each at the University of Pennsylvania, Swarthmore College, and Haverford College. More than 30 scholars from the United States, Britain, and , France delivered papers, including Associate Professor of Religion Ellen Ross, who spoke on “The Radical Reformation of Joshua Evans”; and Curator of the Friends Historical Library Christopher Densmore on “African-American and Quaker Parallel Communities.” Howard M. and Charles F. Jenkins Professor Emeritus of Quaker History and Research Jerry Frost, the keynote speaker for the sessions at Swarthmore, spoke on “Why Quakers and Slavery?” (Read: Professor Frost’s papers.)

Friends Historical Library is a major depository for papers and manuscripts with substantial collections concerning slavery and abolition, and many of the speakers at the conference made extensive use of these collections in their research. Particularly relevant to Swarthmore College is a new biography of Swarthmore founder Lucretia Mott, titled Lucretia Mott: Beloved Heretic, which was written by Carol Faulkner of Syracuse University and will be published by the University of Pennsylvania Press in 2011.

In conjunction with the conference, the Quaker Collection at Haverford College and Friends Historical Library at Swarthmore collaborated on a website on Quakers and Slavery containing original documents and images from their collections. These documents include letters by Lucretia Mott and a recently discovered anti-slavery manuscript from 1805 written by John Parrish, the great uncle of Swarthmore’s first President, Edward Parrish.

Email This Page

Email This Page

February 9th, 2011 3:33 pm

I was pleased to read about the recent symposium on Quakers and Slavery. Friends have often played a vital role in promoting social justice, often in the vanguard of important movements like the abolition of slavery. Yet historically, they have also reflected the viewpoints of the society and time in which they lived. Thus, while certain Friends were leading lights in abolition, others actually held slaves–including native Americans as well as African Americans. Many Quakers who didn't own slaves apparently chose not to "rock the boat" by opposing slavery.

As an institution founded by and exemplifying the values of Quakers, Swarthmore College itself has sometimes been rather behind the times. My father's class (1941) had NO African Americans, yet the College subscribed to egalitarian principles. In rectrospect, this is both astonishing and profoundly disturbing–raising the question: "What could they have been thinking?"

By the time my class matriculated (1967), there were a few African American students, but no black faculty members. The most common positions held by African Americans at the College were menial ones–e.g.., maids and janitors–and they were seriously underpaid. It took an act by a group of African American students–the Admissions Office occupation of January 1969–to jolt the College out of the rut of minimal accommodationism into which it had settled at that time.

While I am certainly inspired by Swarthmore's "Quaker Tradition," and believe that it has played a major role in influecing my own life and values, it has not always played a role in racial progress that many of us might have wanted. To say this is not to deny the inherent values of Quakerism, but to recognize that like any social institution, the Society of Friends is not without its imperfections.