In Honor of Professor Emeritus of Economics Larry Westphal

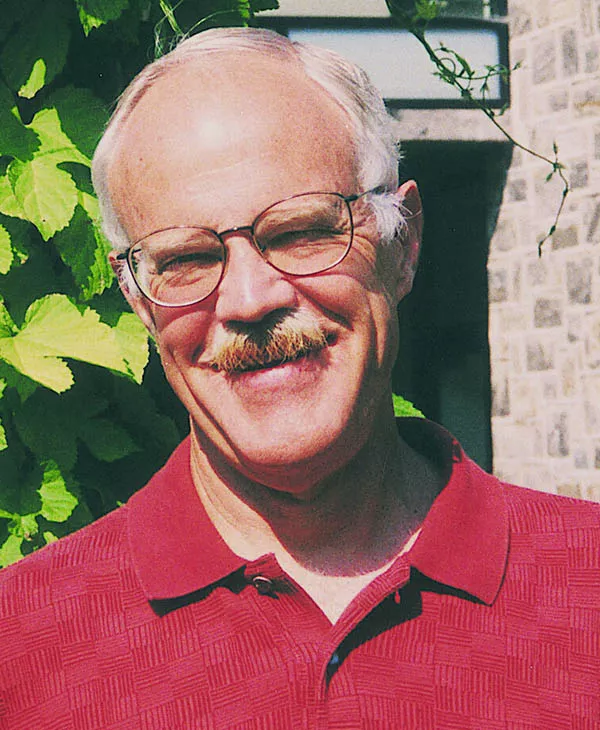

Larry E. Westphal

Dear Friends,

With deep sadness, I write to share the news that Larry E. Westphal, the J. Archer and Helen C. Turner Professor Emeritus of Economics, died of pneumonia in his adopted home of Missoula, Mont., on Wednesday, Nov. 11. He was 78.

Larry is remembered for bringing the rigorous and exacting standards he developed as a leading researcher at the World Bank to his more than 20 years of teaching in the Economics Department and the Environmental Studies Program, which he helped establish. His long-lasting influence extends both to the countries whose governments he advised as well as to the generations of future economists he educated.

Larry is survived by Myrt Westphal, his wife of 56 years and a longtime dean at the College who retired in 2013, daughter and son-in-law Michelle and Carl Thornblade, and two grandsons. He was predeceased by daughter Meredith Alexander, who died at age 42 of an aneurysm in 2018. While COVID-19 prevents a public gathering, his family plans to scatter his ashes in Montana when there is warm sunshine. Any gifts may be directed to the Larry E. and Myrt C. Westphal Scholarship, c/o Swarthmore College, or to the Ocean Conservancy, a lifelong interest.

I invite you to read more below about Larry and his many contributions to our community.

Sincerely,

Val Smith

President

In Honor of Professor Emeritus of Economics Larry Westphal

An influential adviser to East Asian governments as well as to generations of students, Larry Edward Westphal, the J. Archer and Helen C. Turner Professor Emeritus of Economics, died Wednesday, Nov. 11, at age 78. With his passing, Swarthmore has lost an eminent, innovative scholar and a nurturing mentor who left an indelible imprint on his colleagues and the College.

“Larry’s pedagogical and intellectual postures were dedicated to seriousness,” says Philip Jefferson, an economist and Swarthmore colleague who last year became vice president for academic affairs and dean of faculty at Davidson College. “The enduring respect paid to his work on Korea redounded to the Economics Department, his intellectual home.”

“As a departmental colleague, Larry always focused on maintaining our excellence,” says Professor of Economics Ellen Magenheim. “Every subsequent department chair owes him a great deal of appreciation and gratitude for setting up the systems and structures that keep our department running.”

“He brought knowledge of quantitative analytical tools with him that he shared freely with faculty colleagues and students,” says Art McGarity, the Henry C. and J. Archer Turner Professor of Engineering. “My courses benefited dramatically from what he shared with me.”

“Larry was my adviser when I was a student here and has been an important mentor throughout my undergraduate and post-grad career,” says Assistant Professor of Economics Jennifer Peck ’06. “Over the years, I’ve been so grateful for his kindness and wisdom.”

Born and raised in California, Westphal earned his B.A. summa cum laude from Occidental College in 1964 and pursued graduate studies at Harvard University under Hollis Chenery, a leading authority on development economics. Westphal’s thesis, which he researched under the auspices of the U.S. Agency for International Development and concerned two industrial ventures in South Korea, pioneered the incorporation of economies of scale into the development planning models then in vogue.

After receiving his Ph.D in 1969, he joined the Princeton University faculty as an assistant professor of economics and international affairs. He also became a consultant to the World Bank’s special research unit and served as the foreign adviser to the formulation of South Korea’s Second Five-Year Plan, which sought to make the country more competitive in the world market. It was a heady opportunity for a young economist to engage in policy advising to a successfully developing economy.

Westphal left Princeton in 1972 to become an associate professor at Northwestern University, where he continued writing on Korean economic development.

Long a student of East Asian industrialization, Westphal ultimately spent more than 27 months between 1967 and 1974 as a senior adviser to the Republic of Korea’s Economic Planning Board. He considered himself fortunate to work in South Korea because, as a member of the “Gang of Four” along with Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan, it became the model of successful industrialization based on policies that subsidized exports and selectively promoted chosen industries.

In 1974, Westphal joined the World Bank, as the youngest division chief in the Bank’s history, to direct its research division on industrial development. It became the leading center of research on industrial development in the world.

In his 11 years at the World Bank, Westphal focused on the economic engines of emerging Asian economies. During one memorable research trip, he documented Taiwan’s use of the same promotional measures as South Korea, something that was then not known outside of Taiwan due to the country’s secrecy around its industrial policies.

In the 1980s, Westphal became disillusioned with the World Bank’s shift in direction. He believed the Bank’s researchers were entitled to investigate important issues without having their work driven by political ideology. So he returned to academia.

“He bore the professional scars that come from being both unorthodox and, arguably, correct,” Jefferson says.

After intentionally seeking a more intimate environment than he had experienced previously, Westphal came to Swarthmore in 1985 with “no plans to go back into bureaucratic life.” His arrival added significantly to the department’s stature.

“Larry was the eminent presence three doors down our hallway in Kohlberg, and he was a generous intellectual mentor,” says Stephen O’Connell, the Gil and Frank Mustin Professor and Chair of Economics. “His 1990 Journal of Economic Perspectives paper on Korea, ‘Industrial Policy in an Export-Propelled Economy,’ is a true classic. My seminar students read it a week before he died.”

While at Swarthmore, Westphal continued what he considered the important work of consulting on economic development.

In 1986, he worked with the Thailand Development Research Institute’s Science and Technology Program under the auspices of Harvard’s Institute for International Development. He later said this work, to determine how well key industries in Thailand use technology, as well as what policy changes would encourage Thai firms to make better use of technology, took “12 months to plan and 18 months and 20 Ph.D.-level experts to complete.”

Westphal also advised the governments of the Philippines and Indonesia on industrial policy and planning, and served as the principal research fellow at the United Nations University Institute for New Technology in the Netherlands. Additionally, he was a consultant to the U.N. Industrial Development Organization, co-writing and co-editing its first Industrial Development Report.

Despite these high-profile forays, at Swarthmore, Westphal was perhaps best and most infamously known among students for teaching Intermediate Microeconomics, a departmental institution in which, during weekly recitations, the 70 or more students were graded on solving problems in front of the class.

“In that legendary course, he introduced cohorts of students to the rigor necessary to think about economics and the world clearly and precisely,” Jefferson says. “Larry knew what was ahead for Swarthmore graduates. He did not underestimate the importance of his role in preparing them for the future.”

“He took great pride,” says O’Connell, “in having taught at least two decades of economics majors the basics of optimization by households and firms — the core concepts of modern economics.”

Despite the course’s demanding and unabashedly rigorous nature, many students nevertheless embraced it, almost as a rite of passage.

“It was probably the most important class that I took at Swarthmore,” says Peck, “not only because it convinced me to be an economics major, but because it made me feel like I suddenly had this whole new framework I could use to understand the world. Larry’s enthusiasm for micro theory and mastery of its teaching brought a real joy and energy to the subject that highlighted its importance and broad relevance.”

One year, students even made T-shirts, for him and themselves, that read “Team Micro” on the front and stated popular “Westphalisms” on the back, including “No Free Lunch,” “Veritable Conundrum,” and “De Juro Not De Facto” [sic]. The back of his own shirt read “A La Westphal.”

Westphal’s high standards fed his hard-driving reputation, especially among those who could find him rigid and rule-oriented, although “I think he would say ‘deeply principled,’” says John Caskey, the Joseph Wharton Professor of Economics. Yet those who worked most closely with him knew not to define him solely in those terms.

“As I grew to know Larry, I learned that just below the layers of seriousness were wells of warmth, compassion, and care that belied his seemingly stern manner,” Jefferson says.

“He was thoughtful and strived to be fair to others,” Caskey says. “It was not unusual for him to change, or soften, his initial position after some reflection. Larry had a wonderful laugh, and he could laugh at himself as well as anyone could.”

Peck describes stopping by Westphal’s office every week as one of her best college memories. “He treasured his relationships with his former students,” she says, “and would talk proudly of their achievements and postgraduation careers.”

Westphal influenced life on campus beyond the classroom. His “energy and rigor made him the go-to faculty member” for committees tasked with tackling challenging issues, says Magenheim. Indeed, he made significant contributions to the College policies on free speech and intellectual property, and was Economics Department chair from 1987 to 1990. He also served for several years as chair of the Phi Beta Kappa selection committee. And his frequent public talks covered such varied topics as the Third World debt crisis, East Asia’s development success, and the economic challenges involved with protecting the environment.

Westphal’s concern for the environment ran deep, and his passion proved integral to the formation of the College’s Environmental Studies Program in 1992.

“While not originally a specialist in the field, he delved into it early and offered Environmental Economics for over two decades,” says Professor of Engineering Carr Everbach, who served with Westphal on the Environmental Studies committee.

Westphal also loved underwater diving and, from 1994 to 1999, administered and championed the College’s scuba program. The curriculum consisted of three for-credit courses: basic, advanced, and rescue.

“His belief in the economic and geophysical importance of the world’s oceans made him take on this topic as a labor of love,” Everbach says.

Indeed, when Westphal taught the environmental studies capstone seminar on the oceans and the earth beneath the sea, he later described it as his most rewarding teaching experience.

“The devastation he witnessed diving, and that his students documented in detail because of global climate change, helped make several students as passionate as he about the necessity of saving coral reefs and sea life,” says Hans Oberdiek, the Henry C. and Charlotte Turner Professor Emeritus of Philosophy.

In 2000, Westphal was elected a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in the social, economic, and political sciences area “for important contributions to understanding the process of economic growth in developing countries.”

Illness forced Westphal from the classroom in 2006, and he retired from Swarthmore in 2012. The Westphals ultimately resettled in Montana to be closer to their grandchildren.

For a couple who had first met in college and together served as stalwart pillars of the Swarthmore community, it is fitting that a scholarship established in 2011 and awarded annually on the basis of academic merit and financial need honors them equally. The Larry E. and Myrt C. Westphal Scholarship honors Larry Westphal’s teaching excellence and the impact of his microeconomics, economic development, Asian economies, and environmental studies classes, as well as Myrt Westphal’s dedication and work in housing, disabilities, the Lang Scholar program, and personal advising.

“He always joked, ‘When you get rich on Wall Street, buy a gold chair for me,’” Karan Madan ’91, one of three former students who spearheaded the effort, told the Bulletin in 2018. “I was proud to do something even better.”

Westphal — a principled scholar whose seminal publications on a new way of understanding technological development and the economies of Asia continue to be frequently referenced — cared deeply about economic and political injustices and the absolute necessity of fighting global climate change.

“When he judged that something was wrong or someone was wronged, Larry was unyielding,” says Oberdiek, a longtime friend. “But I found that he laughed heartily at life’s absurdities and loved engaging with what makes life worth living, most especially his family.”