Linguist K. David Harrison Helps Endangered Languages Re-emerge

Of the more than 7,000 languages in the world, it is estimated nearly half are in danger of becoming extinct by the end of this century. This month's Smithsonian Folklife Festival program, "One World, Many Voices: Endangered Languages and Cultural Heritage," focused attention on this urgent issue of global language loss by bringing together communities from around the world that are fighting to save their native tongues and cultural traditions.

"Language diversity is part of the bigger picture of sustainability and survival on the planet," says K. David Harrison, co-curator of the program and associate professor of linguistics. "If we care about intellectual diversity, we should also care about language diversity."

The free festival featured participants representing 15 cultures working to preserve their languages. Musicians, storytellers, singers, dancers, poets, culinary experts, and craftspeople shared how language embodies cultural knowledge, identity, values, technologies, and arts. The program included performances, craft demonstrations, interactive discussion sessions, community celebrations and hands-on family activities. This is the first time the festival has featured language preservation as one of its themes.

Harrison hopes that events like the annual Folklife Festival propel people to take back their own ancestral languages and stem the tide of their disappearance. "Everyone can play a part in safeguarding language diversity, by showing interest and respect in other languages, and by realizing that as English speakers we do not have a monopoly on ideas," he tells National Geographic. "Every language contributes its unique genius and singular world view, which can be applied to the solution of common human problems. If people have a heritage language in their family, can work to learn more about it. If they have a Native American heritage language, they can participate in a Breath of Life workshop."

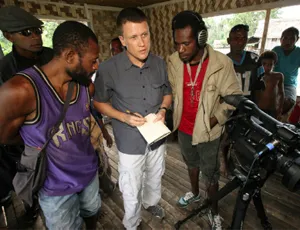

The main challenge in organizing the event, Harrison says, was to take something abstract like language revitalization and put it on at a festival. "Our strategy has been to bring cultural experts - I call them 'language warriors' - from 20 communities from around world who are also experts in material or performative culture," he says. "So, for example, an epic tale teller, basket weaver, or someone who is performing music or dance in a ritual ceremony can also explain why their art would not be possible without their language."

"Language warriors" from the 2013 Folklife Festival include Siletz Dee-ni speakers (top left); Los Masis, performers of Quechua Music from Bolivia (top middle); Lola Palluca de Quispe, a Kallawaya textile weaver from the Upinguaya community of the Bautista Saavedra Province in Bolivia (below Los Masis); Ayana Mongush, a virtuoso Tuvan musician and composer (below de Quispe); Koro craftspeople from India (bottom right), and the Dimen Dong Folk Chorus from Guizhou Province in southwest China (top right).

Harrison's involvement with the festival began three years ago when he was contacted by the Smithsonian about the talking dictionaries he developed as a result of his work with the National Geographic's Enduring Voices Project. The dictionaries - some of which represent the first time that a language has been recorded or written down anywhere - contain more than 32,000 word entries in eight endangered languages, more than 24,000 audio recordings of native speakers pronouncing words and sentences, and photographs of objects from the cultures represented. Read more about his efforts to document endangered languages in The Bulletin.

The Folklife Festival marked the first time that some select languages had ever been spoken in the United States, like Koro (India), and Kallawaya (Bolivia). Other languages, like Penobscot (Maine) and Siletz Dee-ni (Oregon) have been spoken in North American since ancient times.

The highlight for Harrison, he told National Geographic, was a performance by the Kalmyks, a Mongolian people who reside in European Russia on the Caspian Sea. The Kalmyks posess "music, dance, and epic story-telling skills," passed down by "the Kalmyk diaspora community of New Jersey," he says, "which has managed to keep the language and Buddhist traditions alive in this country."

"This is a Swarthmore College project"

Harrison, who joined the Swarthmore faculty in 2001, counts numerous students and alums who have contributed to this work over the years and has recruited several, including Jennifer Johnson '12, as festival volunteers. Johnson worked with Harrison to produce a talking dictionary for the Native American language known as Siletz Dee-ni, spoken in Oregon. Now a graduate student at Georgetown University's Center for Language Education and Development, she helped to "interface" between the Siletz speakers on the Mall, Harrison says, "and to continue her work that she started here in my lab."

The Swarthmore connections even extend to Wren Elhai '08, who first got to know Harrison during his Watson Fellowship year when he was travelling in Russia. Now working for the State Department in Moscow, he met members of the Folklife delegation during a return trip to Tuva in May and saw them off in Moscow. He also connected the Tuvan delegation with friends in Washington, D.C.

For Harrison, his involvement with the festival has been nothing short of amazing. "Ten years ago, I worked as a presenter at the festival on the Silk Road, as part of small delegation from Siberia," he says. "To be invited to be a guest curator is a big honor."

Read more about this year's Folklife Festival in National Geographic, the Huffington Post, and Associated Press.