Theologian Mark Wallace Explores Christian Animism in Recent Book

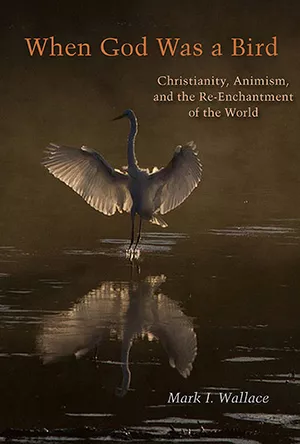

In his recent book, When God Was a Bird, Professor of Religion Mark Wallace introduces himself as a Christian animist — viewing the Earth as a living soul with a spiritual life force.

“All of creation and its many inhabitants are God in a variety of forms and disguises,” Wallace writes in the book, which earned the prestigious Nautilus Gold Award for best book in the category of Religion/Spirituality of Western Thought for 2019.

“It’s a very different take on the Christian religion,” Wallace says, perhaps even heretical for those steeped in a more traditional view of Christianity. But Wallace suggests that Christianity is an Earth-based spirituality — including holy plants, sacred animals, and hallowed landscapes — not an otherworldly, heaven-bound religion.

“There, you’ll see a rich environmental ethic, not a religion about a God who is distant and abstract and invisible, up there in the sky somewhere,” Wallace says. “It’s a way of rethinking Christianity as a way of life, consistent with the cultures and spiritualities of Indigenous peoples.”

Wallace points to the animistic understanding of the world embedded within Christianity, and sounds an urgent call for society to rediscover it. A more human-centric view of the religion has set the stage for our planetary ecological crisis, he told the progressive Christian magazine Broadview, and only by recognizing the spirit of God in nature can we begin to fix it.

Wallace considers his Christian animism a “baseline sensibility,” one he judiciously applies to some of his teaching at Swarthmore. In his Radical Jesus course this fall, he leads sessions on Jesus as an animist, alongside examinations of Jesus as a political revolutionary and nonbinary in a gender sense.

“A huge component of the class is, ‘Hey, everyone, Jesus was Jewish, and there’s a lot of African influence in the formation of the New Testament,’ and that the one thing he wasn’t is a white person,” Wallace says.

“Which raises the question, ‘Why did Jesus become white? What happened?’” Wallace adds. “That’s not really an animist concern, but it has to do with what scholars, particularly in the humanities and social sciences, call critical race theory.”

Understanding subject matter in terms of racial concerns can open up new perspectives on the material that students might not have seen otherwise, Wallace says. To the Radical Jesus course, Wallace invites the believers and unbelievers, evangelicals and atheists.

That spirit of open-mindedness attracted students like Brandon Daniel-Morales ’24, of Quarryville, Pa.

“The description of the course as a level playing field for people of all backgrounds and beliefs to come together and discuss Jesus seemed like something I really wanted to be a part of,” he says.