Q&A with Professor of Linguistics Donna Jo Napoli

“The least visual person alive” just put out a graphic novel.

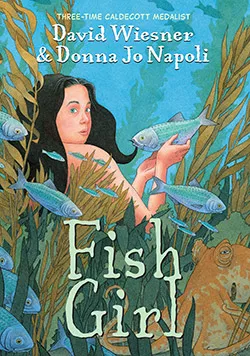

So says Professor of Linguistics Donna Jo Napoli of Fish Girl, which she co-authored with friend and writer/illustrator David Wiesner.

Napoli explains that she grew up with poor vision and, by the time that Wiesner approached her about the project, she thought she was going blind.

“And besides, I just don’t relate to the world visually all that well.”

But when Wiesner showed her a stack of drawings and asked whether she saw a novel in them, something clicked. The authors intertwined perspectives and talents to produce Fish Girl, an adaptation of the Andersen fairy tale that Kirkus Review says “transport[s] readers under the sea, introducing them to a modern-day heroine who longs to be part of their world.”

An award-winning author of more than 70 books for children and young adults, Napoli spoke at TEDxSwarthmore about why banned books are the kinds of books that children should read.

As a linguist, Napoli has authored, co-authored, edited and/or co-edited 17 books, ranging from theoretical linguistics to practical matters in language structure and use, including matters of interest to d/Deaf people. A fellow at the Linguistic Society of America (LSA), she has spearheaded several linguistics conferences and, as the first full-time linguist at Swarthmore, helped build the College’s linguistics program from “a few courses here and there” to a strong and eclectic department. A strong advocate for the deaf and hearing impaired, as well, Napoli received the LSA's 2014 Linguistics, Language, and the Public Award.

She recently sat down to describe how Fish Girl differs from her previous books, how she and Wiesner got out of their comfort zones to produce it, and the challenges of exploring complex themes in a book geared partly to children.

How did your collaboration begin?

David had been making drawings of fish swimming around in houses since he was in art school. He’d been fooling around with them for more than 20 years, but he couldn’t see a story in them. He figured it would gel someday, but it never did. And then he noticed that the graphic novel as an art form had become something that’s really interesting and garnering more respect in recent years — librarians no longer wrinkle their noses when a kid asks for a graphic novel. But to get it to where he wanted it, he came to me, because he thinks in terms of picture books whereas I'm comfortable with novels.

What was your role in the process?

I told David to leave his drawings with me and go away [laughs]. I spread them out on the floor and sat in the middle of them day after day until I started seeing the connections from one to another. I love that kind of puzzle. I had what looked like somebody’s photo album, where they had shaken it and some photos had fallen out at random. I didn't know what order of time they were and who these characters were and how they related to one another. But the puzzle came together over the course of a several months. When I handed David a draft, he said, ‘Oh, this is it.’

To which age groups were you appealing?

That was interesting for us to navigate. I write for all ages, but often fairy tales and fantasy. David writes for much younger people. But this book had some complex themes — it can be read as a tale of abuse. We both had to be comfortable with that and with her age. Portraying a mermaid, who is human and naked from the waist up, is tricky. But since she's just on the cusp of adolescence, I think you can read the story one way as an eight- or nine- or ten-year-old, and another way as a teenager. And adults will read it even more differently, because in my opinion it’s a very dark tale.

What’s your next project?

Right now I’m working on another middle-grade novel called ‘Hunger,’ which starts out in 1846, in western Ireland. So we're already a year into the potato famine, and it looks at this group of families and one girl in particular, and what happens to everyone. It's all about how horrible it is to be starving to death, but also about the injustice of the situation and about how hard it is to think of leaving your homeland to emigrate to somewhere else, and how hard it is to stay behind when there's so little hope behind. I think I got into writing that as I watched the anti-immigration talk that was going on before [the presidential election]. I often write things based on my needs and on how I emotionally respond to something, and that issue just spoke to me very powerfully.