Political Scientist Ayse Kaya Examines Who Foots the Bill for Climate Change

The. following piece is the product of collaborative, original research conducted by Professor of Political Science Ayse Kaya and Kendall Praitis-Hill '23. The pair has studied fragmentation in the current climate finance system and how it can be overcome.

You know how you go out with a friend and you really want to pay, but they do too, so you engage in a tug of war with the bill? That is the opposite of what is going on between rich countries and their less well-off counterparts when it comes to who will pay for climate change-related finance.

What is climate finance? It is funds to reduce greenhouse gas emissions – known as mitigation – and funds to help communities adjust to the negative repercussions of climate change – namely, adaptation. Mitigation funds could be, for instance, for the country to transition away from less clean energy, such as coal, to more clean energies, like solar. Building sea walls and relocating communities to less climate change-impacted areas are adaptation activities.

At the Copenhagen global summit on the climate in 2009, advanced economies promised to "mobilize" $100 billion in climate finance by the end of 2020. This bill is overdue and who will pay for the next one is unclear. When nations gathered in Glasgow for their last climate change summit (COP26), there was less disagreement on whether this $100 billion mark had been missed than by how much. While new pledges by advanced economies, such as the United States, tried to placate developing country discontent in Glasgow, the question remained: Who will pick up the tab?

Countries supply some climate finance directly to another country through bilateral funding, but multilateral financial institutions are supposed to play an important role too. These multilateral banks (MDBs) pool countries’ capital, raise some of their own, and then provide funding for economic development. The World Bank, as perhaps the best known of these multilateral banks, has touted its green credentials for decades now. Just like regular economic development assistance, climate finance is supposed to go from the relatively rich countries to the relatively poor.

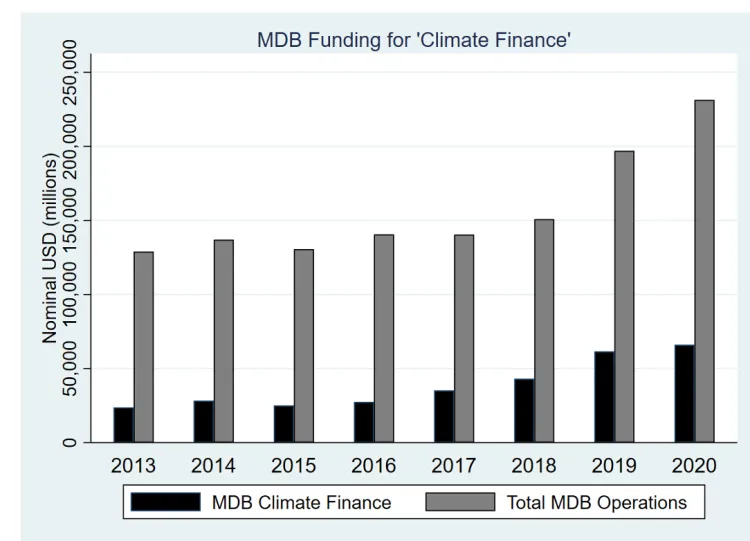

But, our research shows that MBDs’ total lending in climate finance remains lacking and is too heavily tilted toward mitigation at the expense of adaptation (Figure 1). The MDBs report a whopping 70 percent or more of their climate finance going to mitigation in recent years. This is problematic because adaptation funding is sorely needed by poorer countries.

Source: Authors’ compilation from Joint Reports on MDBs’ climate finance.

What can be done? First, MDBs need to more precisely track and count climate finance they and others provide. As is, this accounting does not differentiate different kinds of projects based on how impactful the project promises to be. To give an example, they do not differentiate funding for projects that generate new renewable energy from those that use “dirtier” energy. Counting these various types of projects as the same is akin to calling burgers and salads equally green because they both contain lettuce.

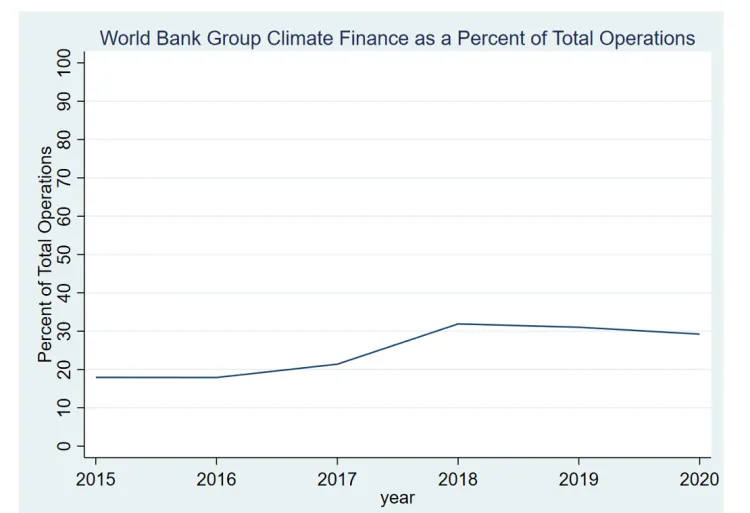

Second, Americans and their allies as dominant shareholders in the World Bank can do more than just up the pressure for climate finance. The World Bank has been the dominant multilateral development bank: it has the largest membership and a non-regional mandate. The Bank can commit itself to only lending for environmental projects for the next several years, while doing more impact evaluation on these projects (Figure 2).

This would overcome the fragmentation in the current climate finance system and focus the Bank on a worthy goal. This could do the Bank a lot of good, too, at a time when it has to increasingly compete with new multilateral banks, such as the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. A full force commitment such as this can also send a stronger signal to private markets. Before the Bank can get there, however, it should rapidly develop more rigorous methods of counting the environmental contribution of its own projects toward adaptation and mitigation.

Source: Authors’ compilation from Joint Reports on MDBs’ climate finance.

Third, the relatively well-off emerging nations, such as India and China, need to take significant steps. China committed to stop financing for the building of new coal plants abroad. But, International Energy Agency numbers indicate that in 2019, China’s reliance on coal was not much better than its reliance on it nearly three decades earlier; about 60% of its energy is supplied by it. As the world’s current largest emitter, China cannot forever ride on the coattails of “historical responsibility” of today’s rich Western economies to greenhouse gas accumulation.

There is, however, a silver lining: thanks to climate change science and scientists’ communication efforts, the ecological toll on the Earth is so apparent that the debate has shifted to tools, including climate finance, to fight the damage. Now, there is at least the recognition that it is time to pay up.