New Study Traces Evolution of Birds from Dinosaurs

Photo credit: Jason Brougham (University of Edinburgh)

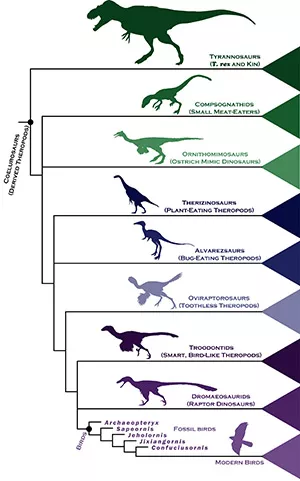

Associate Professor of Statistics Steve C. Wang is part of a team of researchers that has created the most comprehensive family tree of meat-eating dinosaurs ever, giving fresh insight into the rapid evolution of birds.

The study, which is published in the journal Current Biology, shows that the familiar anatomical features of birds – such as feathers, wings and wishbones – all first evolved piecemeal in their dinosaur ancestors over tens of millions of years.

However, once a fully functioning bird body shape was complete, an evolutionary explosion began, causing a rapid increase in the rate at which birds evolved.

Based on their findings from fossil records, researchers say the emergence of birds some 150 million years ago was a gradual process, as some dinosaurs became more bird-like over time.

“The evolution of birds from their dinosaur ancestors was a landmark in the history of life,” says Wang. “This process was so gradual that if you traveled back in time to the Jurassic, you’d find that the earliest birds looked indistinguishable from many other dinosaurs.”

Wang adds that “birds as we know them evolved over millions of years, accumulating small shifts in shape and function of the skeleton. But once all these pieces were in place to form the archetypal bird skeleton, birds then evolved rapidly, eventually leading to the great diversity of species we know today.”

The team of researchers, which was led by the University of Edinburgh (UK), examined the evolutionary links between ancient birds and their closest dinosaur relatives. They did this by analyzing the anatomical make-up of more than 850 body features in 150 extinct species, and used statistical techniques to analyze their findings and assemble a detailed family tree.

For the study, Wang invented a novel statistical method that was able to take advantage of new kinds of data from the fossil record, which reached the conclusion that early birds had a high rate of evolution.

“The fossil record is a treasure chest of clues to the evolution of life,” he says, “but how you look at the data determines what kind of patterns you can find, and if you can discover patterns that are not obvious.”

Findings from the study support a controversial theory proposed in the 1940s that the emergence of new body shapes in groups of species could result in a surge in their evolution.

The work was supported by the European Commission, National Science Foundation, the University of Edinburgh, Swarthmore College’s Research Fund, Swarthmore College’s James Michener Faculty Fellowship, Columbia University, and the American Museum of Natural History.

The study has been featured in numerous media outlets around the world, including The Telegraph (U.K.), Forbes, Scientific American, National Geographic, Discovery Channel, and Times of India.