For the Love of Frogs: Itzue Caviedes Solis, Trailblazer in the Field of Herpetology

Assistant Professor of Biology Itzue Caviedes Solis is leading the way for more women to enter the field of herpetology, the study of reptiles and amphibians. Caviedes Solis, from Iztapalapa, Mexico City, was raised to prioritize education, bravery, compassion, and advocacy for women and underrepresented minorities.

Through her teaching, fieldwork, and writing, Caviedes Solis shares her love of tree frogs, and hopes to inspire others to pursue a life of continuous curiosity. This past year, Caviedes Solis had two books published and completed two field research trips, including a trip with Swarthmore students.

“I write not just for other scientists in scientific journals, but for everyone, using my scientific background to promote equity and not to perpetuate elitism,” says Caviedes Solis. “I hope all of us, kids, adults, elderly — see frogs and scientists, especially underrepresented minorities like myself, in a different light, with curiosity and awe instead of fear and judgment. My way to change the world is, I hope, one frog lover at the time.”

Caviedes Solis’ children's book, Frogs (A Day in the Life): What Do Frogs, Toads, and Tadpoles Get Up to All Day?, is an illustrated journey into the world of frogs, following their lives as they dance, hunt, and fight. Her second book, Women in Herpetology: 50 Stories from Around the World, showcases the inspiring journeys of 50 women from 50 countries and regions, sharing stories from their fields of specialization.

The herpetologists profiled in the book range from 20-80 years old, and work in fields such as conservation, ecotoxicology, and education. Themes in the book include the challenges that women face in herpetology, from limited resources and mentorship opportunities, to the profound joys they’ve found through their work. Seventeen women artists from around the globe illustrated the book with whimsical portraits of each herpetologist.

Illustrations from Women in Herpetology. (From left: Itzue Caviedes Solis by Ximena Cuenca, Norhayati Ahmad by Vernnie Chong, and Nunia Thomas by Annabelle Hale)

The book was a three-year project, created with herpetologists from The Global Women in Herpetology Project: Sinlan Poo, curator of research scientist at the Memphis Zoo and adjunct assistant professor at Arkansas State University, from Taiwan; and Umilaela Arifin, Marie Curie Research Fellow at the Center of Natural History in Hamburg, from Indonesia.

“Being an author of these books is opening a door to a world that was closed, or open only for a select group of people when I was younger,” says Caviedes Solis. “Behind that door there is a world full of herpetology wonders, and passionate people around the world working with them. I want everyone to be able to enjoy it and be part of it.”

In Tiputini, the Ecuadorian Amazon Rainforest, Caviedes Solis is washing a frog before swabbing it. (Brian Katona)

Women in Herpetology doesn’t seek to simply inspire future female herpetologists, but to also financially support them on that journey. All profits from book sales will be used to establish a scholarship for students in underrepresented regions to attend the World Congress of Herpetology to present their research.

“We strongly believe that every voice counts and every story matters,” says Caviedes Solis. “We aim to help create a world where we are all welcome, where we all feel like we belong. A world where a herpetologist looks like any of us, looks like any of you."

Bryn Mawr student N’Diaye ’24, and Swarthmore's Kim ’25, Holmes ’25, Caviedes Solis, and Wyatt ’25 doing outreach at Swarthmore Public Library. (Brian Katona)

Caviedes Solis enjoys the hands-on nature of field work, and brings her students right along. During the 2022-23 academic year, Caviedes Solis and her students Aimi Holmes ’25, Stephanie Kim ’25, Isabella Wyatt ’25 and Bryn Mawr student Leila N’Diaye ’24 studied amphibians in the Crum Woods and did outreach at the Swarthmore Public Library, teaching children about local wildlife.

This past summer, they ventured to a tropical climate with much greater amphibian diversity.

Caviedes Solis and students in the Crum Woods (left), and photographed by Brian Katona in Mexico (right).

Before meeting with Swarthmore students in Mexico for field work, Caviedes Solis’ amphibian-centric summer began in the Ecuadorian Amazon. She worked in the Tiputini Field Station located in the Yasuní National Park.

Yasuní is considered one of the last remaining wilderness areas on the planet with large areas of intact forest. The park hosts extraordinary amphibian diversity: Of the 150 species recorded through the park, 141 are frogs. That's more than the total number of frog species native to the U.S. and Canada combined.

Yasuní and its amphibian population face multiple threats including oil extraction, mining, logging, oil palm plantations, and large-scale transportation projects. Due to the permeability of their skin and their dependency on water, amphibians are important bioindicators, which means their presence and health reveal the quality of the environment. Anthropogenic, or human-induced, disturbances in ecosystems expose amphibians to pollutants that weaken their immune system and alter the composition of microbial communities on their skin. These microbial communities consist of microorganisms that are vital to amphibian populations.

In collaboration with Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador Professor Santiago Ron, Caviedes Solis’ research project in Yasuní National Park aims to characterize the microbial communities of amphibians.

After Ecuador, Caviedes Solis traveled to the Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve in Jalisco, Mexico, to begin six weeks of studying frogs with Holmes, Kim, and Wyatt. Caviedes Solis’ lab fosters teamwork: Each student conducted their own research project while also collaborating to collect each other's data.

Stephanie Kim ‘25 holding a frog in Jalisco, Mexico. (Brian Katona)

Kim focused on comparing the oral and gut microbiome of toads. The comparison will allow scientists to understand if the oral microbiome assists with digestion of certain foods and how the oral microbiome changes after passing through the gastrointestinal tract.

In her field study reflections, Kim wrote, “While I’ve seen dense forests before, actually walking through them is such a unique experience. Sometimes, I can’t even see the path! We saw many types of animals. We’ve seen frogs, snakes, tarantulas, deer, and more. The way the false coral snake stuck its head above the grass to search for lizards was so amazing to watch. We even saw a scorpion eating a lizard! While here, it’s fun to think about all of the scientists that walked the same paths, ate at the same cafeteria, and used the same classroom during their stay at this field station. I wonder what research they did and how that research expanded their career.”

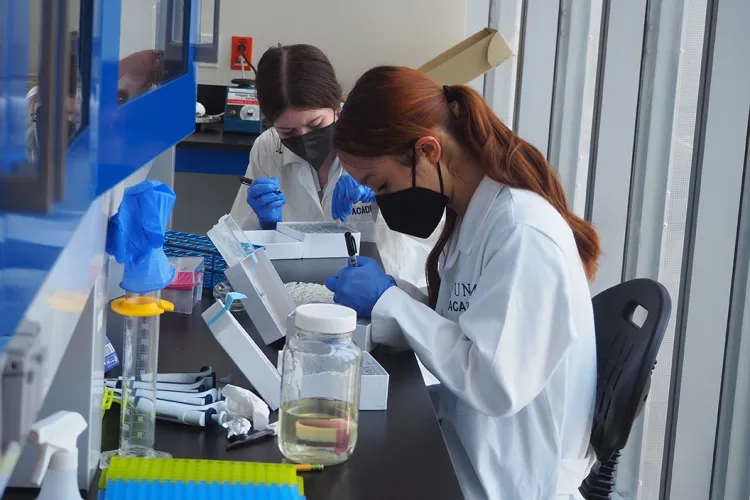

Following their field work, Caviedes Solis and her students began work at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) laboratories in Mexico City.

Aimi Holmes ’25 (seated in foreground), working in the UNAM lab. (Brian Katona)

Holmes, whose project focused on understanding the relationship between microbial communities in the GI tract and diet composition, reflects on the gratification of lab work.

“The attention to detail, precision, and satisfaction of extracting DNA has definitely been one of my favorite parts of research,” says Holmes. “Working in the labs at UNAM and spending time exploring Mexico City have been very rewarding as I’ve found that I truly enjoy doing lab work. Additionally, being able to do lab work on such a beautiful campus and being surrounded by such hard-working women was an incredible experience and I really hope I get to work in an environment like that in the future.”

“I would like to thank my faculty supervisor, Dr. Itzue Caviedes Solis, as she provided immense amounts of support and continuously encouraged us to all be confident in our abilities. I couldn't have asked for a better experience, thanks to her.”

Isabella Wyatt ’25 holding a frog in the UNAM lab. (Brian Katona)

Wyatt aimed to assess the effectiveness of frog skin-swabbing protocols. She compared swabbing in situ (in the field) and ex situ (in the lab), as well as the importance of the body region that is being swabbed (dorsal versus ventral). As the group’s time in Mexico City drew to a conclusion, Wyatt wrote about how this experience reaffirmed her decision to pursue a career as a scientist.

“I am extraordinarily grateful to have had the opportunity to have had this research experience in both extraordinary (and extraordinarily different) locations, and truly hope to return to both someday. I think that perhaps my favorite thing about this type of science is seeing that people are in their fields out of a love and passion for the creatures they study, and knowing that there are scientists out there who deeply love creatures I have never given a second thought to. I look forward to joining them [as a scientist] someday."