Linguist K. David Harrison Continues to Grow a Repository for the World’s Endangered Languages

K. David Harrison works with Anselon Seru on Futuna Island, Vanuatu, in 2018. Photo by R. Sean Thackurdeen ’12.

More than 2,500 languages are at risk of extinction, as speakers face pressure to abandon their native tongue in favor of dominant dialects. The preservation of these minority languages has a clear social impact, by advancing indigenous rights and keeping cultural connections alive.

But there’s an environmental element to their conservation, as well: With the loss of a language also comes the loss of a knowledge base — especially as related to local flora and fauna that has yet to be catalogued by the scientific community.

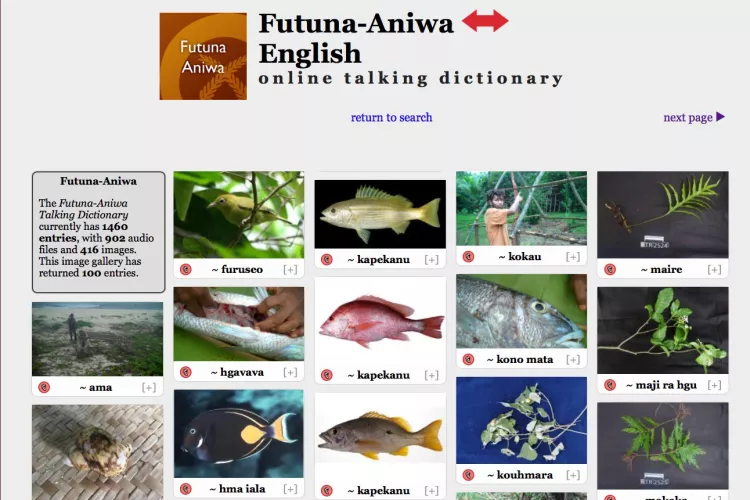

This summer, despite the challenges presented by COVID-19, a team of linguists from the Tri-College Consortium helped preserve nine of these endangered languages — and expand on research related to six others — through their work on Talking Dictionaries, a collaborative platform created by Swarthmore Professor of Linguistics K. David Harrison and Kit LaTouche '08 in 2005. Unlike a typical printed dictionary, these online collections of minority languages feature photos, videos, tweets, and audio recordings of words and phrases, enabling even languages without a writing system to be preserved. The platform, hosted at Swarthmore, encourages exploration of both a language and its culture.

In many cases, a Talking Dictionary is an indigenous language’s first presence on the internet, Harrison says, providing affirmation for speakers in these communities that their language is not only valid, but also valued.

“They’re getting negative messages from all sides saying your language is backwards and obsolete and useless,” says Harrison, an “old-fashioned field linguist” and advocate for the revitalization of endangered languages. “We’re helping with the pushback, saying your language is just as suited for the internet as any other language. And here’s proof of it.”

Over the past 15 years, the Talking Dictionaries project has grown to include 200+ languages and attracted more than $1.2 million in grant money from the National Science Foundation, National Geographic, all three Tri-Co colleges, and private donors. Harrison believes that the eight Tri-Co faculty members contributing to the work — including himself, Ted Fernald, Emily Gasser, Rikker Dockum, and Jeremy Fahringer at Swarthmore, and Brook Lillehaugen, Felipe Lopez, and Kate Riestenberg at Haverford — may constitute the largest digital lexicography faculty cohort anywhere in the world. The project has also brought indigenous experts to speak at Swarthmore, most recently last fall in a visit supported by the Lang Center for Civic & Social Responsibility.

This summer’s research, which involved remote, global partnerships to record and process the endangered languages, resulted in new Talking Dictionaries for languages of Indonesia, Myanmar, Vanuatu, Russia, and the Crimean Peninsula, as well as a highly endangered Native American language.

To create a dictionary, the linguists might start by working with local cultural consultants to identify and photograph common tangible objects — broom, cooking pot, teapot, etc.; the photos are then paired with audio recordings of the words provided by native speakers. The project later expands to include simple verbs, with videos of people acting things out, before moving on to more abstract ideas, such as feelings or metaphors.

Over the course of his research, Harrison noticed that the speakers of these endangered languages were especially eager to discuss their environment — particularly the plants, fish, and domesticated animals that were key to their culture. This realization added a layer of importance to the project, in that saving languages also enables the saving of the environment.

To create a dictionary like the one above, linguists might start by working with local cultural consultants to identify and photograph common tangible objects, then the photos are then paired with audio recordings of the words provided by native speakers.

“Most plants, for example, that exist in the world are not known to botanists,” Harrison says. “They haven’t been named or catalogued or indexed yet, but they’re very well-known to local people. And they not only have names in all these languages, but people know about their medicinal properties and their uses. That knowledge base is vast, but it only exists in the minds of the people who speak these endangered languages.

“By cataloging and collecting that knowledge,” Harrison adds, “we’re cataloging basic knowledge that’s new to science. That’s very important for saving the planet and being good stewards of the Earth.”

As a result, Harrison has collaborated with scientists from the New York Botanical Garden — including, at one time, R. Sean Thackurdeen ’12 — to document languages and plants in the island nation of Vanuatu, a biodiversity and language hotspot with 113 languages in a population of just 280,000 residents. That research has yielded six Talking Dictionaries of Vanuatu languages so far, with botanists expecting to identify about 500 plants that are new to science.

Dozens of students have taken part in the Talking Dictionaries project, as well, including through onsite fieldwork. For Ceci Williamson ’22, who in summer 2019 worked on Zapotec language documentation and revitalization in Oaxaca, Mexico, the experience was so impactful that she changed her course of study, from engineering to a double major in linguistics and biology.

“While I enjoy linguistics classes and studies on campus, the ability to experience firsthand the ties that the Zapotec languages have to the culture and environment was eye-opening for me, and it really showed me how broad of a discipline linguistics is,” says Williamson, of Madison, Wis. “Language documentation through a project like the Talking Dictionaries is more than just generating a corpus of data, or putting soundbites on a website — it's one way of preserving living traditions and supporting language activists.”

Harrison’s hope is for the project to continue to grow: Although 200 Talking Dictionaries may seem like a lot, he says, out of the world’s 7,000 languages, “it’s a drop in the bucket.” Another goal is to transfer the intellectual property to Swarthmore, and to recognize and celebrate the support that the College has provided for the project.

“Swarthmore has unwittingly become a repository for the world’s endangered languages — but a living repository, not somebody stored some data away somewhere under lock and key,” Harrison says. “We put the data, publicly facing, on a free platform that supports indigenous rights and indigenous languages.

“I'd like the College to get credit for this,” he adds, “because it has great global impact. And it's doing something to advance and support cultural diversity and language diversity — which are the same thing.”