In Honor of Swarthmore’s 11th President Theodore Friend

President Valerie Smith shared the following message with the campus community on November 12, 2020:

Dear Friends,

With deep sadness, I write to share the news that Theodore “Dorie” Friend, who served as Swarthmore’s 11th president from 1973-82, died of cancer at his home in Villanova, Pa., on Wednesday, Nov. 4. He was 89.

An award-winning historian who pursued his scholarly interests with passion and conviction, Dorie came to Swarthmore with the goal of rebuilding trust and a sense of community on campus after the challenges of the late 1960s and early 1970s. I was fortunate to spend time with him on numerous occasions and enjoyed his warmth, candor, wisdom, good humor, keen insights into the history and culture of the College, and wide-ranging intellectual curiosity.

Dorie is survived by sons Tad and Pier, daughter Timmie Friend Haskins, five grandchildren, and his companion Mary French. He is predeceased by Elizabeth Pierson Friend, his wife of 43 years, who died in 2003. A private service has taken place, and plans for a public memorial will be shared when they are available. In lieu of flowers, please direct any gifts to the Theodore Friend and Elizabeth Pierson Friend Scholarship c/o Swarthmore College, the Eisenhower Exchange Fellowship Foundation, and the voting rights organization Fair Fight.

I invite you to read more below about Dorie and his many lasting contributions to our community.

Sincerely,

Val Smith

President

In Honor of Swarthmore College’s 11th President Theodore Friend

A prodigious scholar and former Swarthmore president, Theodore Wood Friend, III, known by all as “Dorie,” died Wednesday, Nov. 4, at age 89. With his passing, Swarthmore has lost a widely-respected repository of institutional memory and one of its most engaging and enthusiastic advocates — known for his gracious leadership style and his ability to balance a wide range of competing institutional interests and priorities.

“Dorie was a man of great knowledge and wisdom who carried himself with such grace and kindness,” says Rebecca Chopp, who served as Swarthmore’s president from 2009 to 2014. “He was a friend and mentor, helping me learn about Swarthmore’s history as only a former president and historian could.”

David Fraser, who succeeded Friend, describes him as “a talented and eloquent historian who proved to be a formidable fundraiser.”

“I had the good fortune to meet him often over the succeeding years, which was a blessing because he was warm, wise, and generous,” says former College Vice President Maurice Eldridge ’61, who returned to Swarthmore three years after Friend’s term as president had ended. “He was always positive when our paths crossed and ready to share his wisdom.”

A native of Pittsburgh and a lifelong Pirates fan, Friend attended St. Paul’s School in Concord, N.H. In 1953, he earned a B.A. from Williams College, where he won a contest to name Ephelia, the school’s ubiquitous purple cow mascot. He later received a Ph.D. from Yale University and pursued his studies as a Fulbright Scholar in the Philippines, where his work formed the basis for his first book, Between Two Empires: The Ordeal of the Philippines, 1929–1946 (1965). It won the prestigious Bancroft Prize in American History, Foreign Policy, and Diplomacy.

In 1959, Friend joined the history faculty of the State University of New York at Buffalo, where he taught for 14 years before being selected as Swarthmore’s 11th president — with perhaps the most Quaker-like of names in College history. In his inaugural address, in 1973, he said:

“Swarthmore is one small center trying to educate the necessary humane feeling, rigorous thinking, and social responsibility to ensure that we do not prove to be, as a species, our own conclusive enemy. … We must set ourselves, construct our curriculum, and inform our teaching to ensure that those who graduate from Swarthmore will bring to the world a spirit that does not shrink at the apparently insurmountable.”

“The Board somehow had faith in me,” Friend told the Phoenix many years later, “even though I had never administered anything!”

Friend faced a number of challenges at Swarthmore. Just a few years before, one predecessor had died in office, and another had held the position only briefly. Within a year of his taking office, the value of the College’s endowment dropped more than 50%. The country was also in the midst of the Vietnam War and the Watergate crisis, and confidence in the nation’s leadership was at a low ebb. Six weeks after he began work in Parrish Hall, Friend found that his office had been trashed by students who were protesting America’s engagement in Vietnam — a war that he had long publicly opposed.

Although he acknowledged that his years in office were difficult, Friend accomplished a lot during his tenure. He reinvigorated the Honors Program, successfully completed the College’s $30 million Program for Swarthmore campaign, and oversaw a significant increase in admissions applications, which ran counter to national trends.

Priorities for the Program for Swarthmore campaign included new scholarships, professorships, and curriculum development. The Program also supported construction of Cornell Science Library, Ware Pool, and Mertz Hall, as well as improvements to several academic buildings. Upon the campaign’s conclusion in 1981, the Board of Managers honored Friend and his wife, a vital presence on campus, by creating the Theodore and Elizabeth Friend Scholarship. It is awarded annually on the basis of financial need to a worthy student.

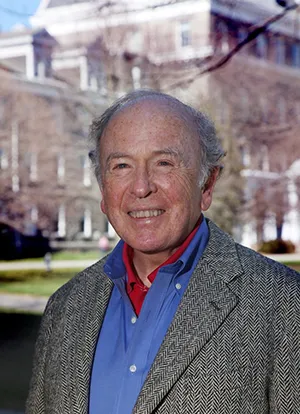

Dorie Friend, 2011

Also during Friend’s tenure, the faculty gained a greater voice in setting College policy.

“I just assumed that it was the way colleges work,” says Barry Schwartz, the Dorwin P. Cartwright Professor Emeritus of Social Theory and Social Action, who was a young faculty member at the time. “I came to realize only in retrospect how unusual it was to feel heard and respected no matter what your role at the College was. These were challenging times for colleges and universities, but Dorie managed to keep the ship afloat. He helped set a tone that I think has persisted to this day.”

In the mid-1970s, one of those challenges at Swarthmore was a class-action gender discrimination suit alleging unfair treatment of female faculty members. Although the suit was ultimately decided in the College’s favor, it exposed some concerning practices. In response, Friend established a new, part-time position for an equal opportunity officer. The College also adopted a nondiscrimination employment policy.

Friend threw himself, sometimes literally, into the work of connecting with students and the campus community. In his first year at Swarthmore, he played pickup soccer with the men’s team in a match against the football team — and got run over by a football player. The collision severed his ACL.

“I remember he was on crutches during my interview,” says Constance Hungerford, the Mari S. Michener Professor Emerita of Art History and Provost Emerita, who served as interim president in 2014-15 and retired from the College this spring. “I also remember how reassuringly enthusiastic he was about what I would bring to the campus.”

On another occasion, during the College’s 1976 Oktoberfest celebration, a tug of war took place across the Crum Creek — students vs. the provost, the registrar, two faculty members, and Friend. The more senior team was dragged, amid cheers and catcalls, into the creek.

Friend held open office hours for students and took an active interest in student concerns. Late in his tenure, he also co-taught a class on Southeast Asia with religion professor Don Swearer, something he wished he had done sooner.

The Friends regularly hosted salons in their home for members of the community, to connect people they thought would enjoy talking with one another. Elizabeth Friend kept records of the seating arrangements and menus so that when guests returned, they would sit next to someone new and were never served the same meal twice.

“He and Elizabeth delighted in sharing their own very rich experiences to build connections throughout the community,” Hungerford says, “and I valued his personal interest even after he moved on from Swarthmore.”

Friend was also a devoted squash player; for a single week in 1965, he was the top-ranked player in Buffalo. At Swarthmore, he often joined members of the men’s team on the College’s frigid courts. When a women’s team was established in 1976, he offered his help — ultimately coaching each of the club’s nine members, most of whom had never played before, by playing with them twice a week. He also attended their matches, watching with characteristic restraint but following their every stroke with pride and concern. The following season, the team sent four players to a national women’s intercollegiate tournament.

“He was always able to take up a position in the middle of the court, and getting around him was like getting around a mountain,” remembers J. Lawrence Shane ’56, who joined the Board of Managers shortly before Friend’s arrival. “Needless to say, he beat me every time.”

Squash continued to be one of Friend’s main pursuits, and in 2007, he was a finalist in the U.S. Open Championship’s 75+ division.

Throughout his tenure as president, Friend steadfastly upheld the College’s mission. “There is something really quite extraordinary about the learning atmosphere here,” Friend said, “and that is really where my satisfactions ultimately are.”

In 1982, the Phoenix ran an op-ed in the last issue of Friend’s presidency that concluded he left a legacy “far greater” than the actions he carried out during his formal duties as president:

“He has been a sensitive and articulate educator, bringing a strong academic vision to this rigorous intellectual community. Most of all, he is a warm and caring person whose personal presence we will all miss.”

During that year’s Alumni Day, the Friends were given honorary memberships to the Swarthmore College Alumni Association. “We’ll always be attached by heartstrings to the College,” Friend said.

After Swarthmore, Friend served as president of the Philadelphia-based Eisenhower Exchange Fellowships Foundation (EEF) from 1984 to 1996. He had joined the board two years prior with the help of Tom McCabe, a member of Swarthmore’s Class of 1915 and the organization’s founding chairman. The foundation brings emerging world leaders to the U.S. for a program in their field and sends American professionals abroad.

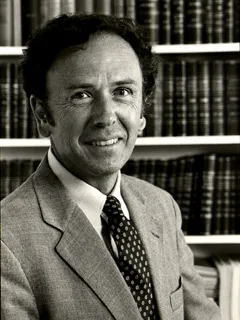

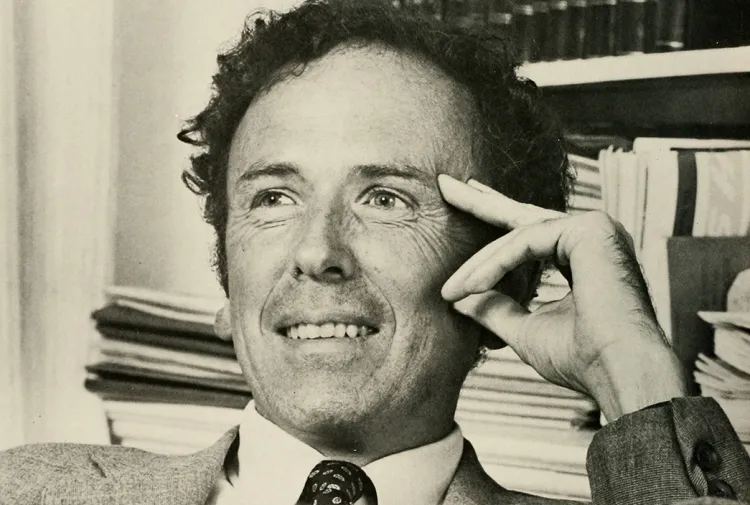

Dorie Friend in the 1982 Halcyon

As president, Friend built the organization’s endowment and brought to the U.S. the first fellows from China, El Salvador, Mozambique, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. In addition, Guatemala and Iraq participated in the program after a 25-year hiatus. His fundraising prowess at both Swarthmore and EEF led him to call himself a “not-for-profiteer.”

Leading the fellowship program allowed Friend more time for his writing. He published a novel, Family Laundry (1986), in which The New York Times said he “conducted a difficult inquiry” into an upper-middle-class Anglo-Saxon family and its intentions and failures “with energy, sensitivity, and determination.” The following year, he published The Blue-Eyed Enemy: Japan Against the West in Java and Luzon (1988), a comparative history of Indonesia and the Philippines under Japanese rule. Work on the latter was supported by a Guggenheim Fellowship.

Friend left EEF in 1996, though he remained a trustee. He also served for many years as a senior fellow in the Asia Program at the Foreign Policy Research Institute. In 2004, he served as the C.V. Starr Distinguished Visiting Professor of Southeast Asia Studies at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies.

Friend went on to publish three more works of history and analysis. In Indonesian Destinies (2003), he examined the Indonesian nation state from revolution against the Dutch through the solving of the 2002 terrorist bombings in Bali. The book received the best reviews of his career, and was considered a landmark in studies of the country. He also edited a collection of essays, Religion and Religiosity in the Philippines and Indonesia (2006). And in 2011, he published Woman, Man, and God in Modern Islam, a comparative study of the life of women in Indonesia, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Turkey.

Yet Friend, who lived in Villanova, was never far from campus for long. In 2005, he established the Theodore Friend and Elizabeth Pierson Friend Scholarship for a student from an Islamic country or a student engaged in Islamic studies. He attended the presidential inaugurations of Rebecca Chopp in 2010 and Valerie Smith in 2015. He also spoke on campus in 2012 about his journeys across Asia and the Middle East.

In his inaugural address, Friend said he eschewed the “well-rounded person” as an educational but empty ideal, noting that “ball bearings are well-rounded, well-tooled, and useful, but they supply neither motive power nor direction.” An “intellectual person” was not a satisfactory ideal either, because he said it stresses “only a part” of being human.

Instead, in articulating his aspirations for the College, Friend shared his own lived ideals when he concluded: “In any summary phrase there is the danger of saying both too little and too much. I knowingly risk that danger in saying that we will do well to think of educating moral persons. To me this means whole persons, aspiring to excellence in chosen fields and pursuits and putting thought, word, and act to the tests of integrity.”