In Honor of Emeritus History Professor Bernard Smith

President Valerie Smith shared the following message with the campus community on February 11, 2021:

Dear Friends,

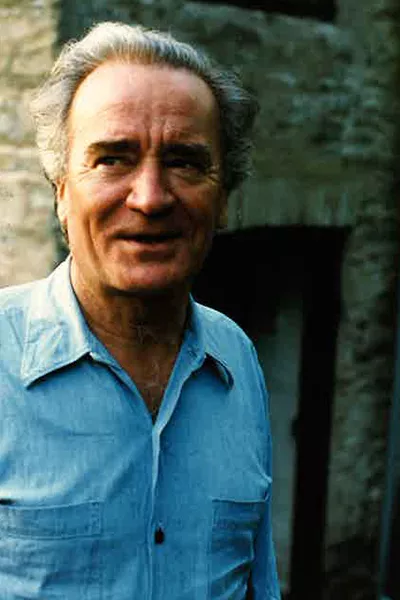

With deep sadness, I write to share the news that Professor Emeritus of History Bernard Sidney Smith died in Wales on Sunday, Jan. 31. He was 95.

Bernard, who served on the faculty for 18 years, is remembered as a passionate medievalist and erudite scholar with an understated, dry wit, as well as a key inspiration to the College’s Medieval Studies Program.

Bernard was married to Nancy Smith, who worked at Swarthmore for several years as an editor of the Bulletin, the College’s alumni magazine; they divorced in 1980. She survives him, as do their children Jessica, Matthew, Daniel, and Hugh, and two grandchildren. While COVID-19 prevents a public gathering at this time, any gifts in his name may be directed to the Royal Oak Foundation, the U.S. branch of the National Trust (U.K.), of which he was a devoted member.

I invite you to read more below about Bernard and his many contributions to our community.

Sincerely,

Val Smith

President

In Honor of Emeritus History Professor Bernard Smith

Professor Emeritus of History Bernard Sidney Smith died Sunday, Jan. 31, at age 95. With his passing, Swarthmore has lost a learned and staunch defender of academic ideals who was instrumental in shaping the College’s Medieval Studies Program.

“Bernard was a brilliant medieval historian who knew early British and European history intimately and taught it with a keen intellect and wry wit,” says Craig Williamson, the Alfred H. and Peggi Bloom Professor of English Literature. “He was a mentor to me and to other medievalists who came to Swarthmore and was a good friend and guiding light to many of us.”

Bob DuPlessis, the Isaac H. Clothier Professor Emeritus of History and International Relations, also remembers Smith as a thoughtful, careful scholar and helpful mentor.

“We taught a combined medieval and early modern Europe survey my first semester,” DuPlessis says, “during which he gave me, both explicitly and by his practice, a number of useful pointers about teaching.”

“Bernard Smith, as anyone will tell you, did not suffer fools gladly, leaving the rest of us to wonder what banality we may have committed,” says Bob Bannister, the Scheuer Professor Emeritus of History. “Among his many charms was a solid-gold Oxbridge accent that allowed him to take command of any room he happened to occupy. When Bernard spoke, people listened.”

Smith came by his accent honestly. Born in London, he left his undergraduate studies at Trinity College, the University of Oxford, in 1946 to join the British Army, serving in India during partition. After returning to Oxford, he roomed with J.R.R. Tolkien’s son Christopher, forging a decades-long relationship between their families.

Smith earned a B.A. in 1950 and an M.A. in 1952 from Oxford, then joined the British Foreign Office. Over the next six years, he received a certificate in Russian from the University of Cambridge and spent two years in Berlin working for the BBC; he ultimately learned seven languages. Smith took the Official Secrets Act seriously and never discussed his foreign service work.

In 1959, Smith came to the U.S. to teach at the University of Florida, then pursued a Ph.D. in history at Harvard University, completing his dissertation on the life and work of Rupert of Deutz, an influential Benedictine theologian in the 12th century. He then taught at the University of Delaware before joining Swarthmore's history faculty as an assistant professor in 1967.

A medievalist with a reputation as a demanding yet inspiring teacher, Smith centered his research and courses on 11th- and 12th-century monasticism, medieval intellectual history, German medieval history, and late-medieval Europe. The Medieval Studies Program, drawing from history as well as classics, art history, and religion, among other subjects, offered its first major in the 1971–72 academic year.

In 1970, Smith received a fellowship from the American Council of Learned Societies to spend a year in England editing a collection of official documents, dated 1130 to 1216, including royal and papal letters, rent rolls, and other papers from the county record office in Winchester. The material appeared as a volume in a series produced by the Hampshire (England) Records Society.

In addition to reviews and essays, Smith edited and translated The Orders and Callings of the Church (1972) with his Harvard colleague Giles Constable, and translated Early Medieval Germany (1978) by historian Josef Fleckenstein.

Smith’s service to Swarthmore included membership on the Council for Educational Priorities and the Committee on Faculty Procedures, as well as a student-faculty committee on admissions and scholarship. He also took principled stands that sometimes ran counter to College positions. In 1970, when the College signed an agreement, albeit “under protest,” with a Pennsylvania agency that sought to tie state financial aid to students’ criminal history, Smith objected on principle, warning of the “ominous precedent” for further encroachment on academic freedom the agreement would cause.

Smith was also a director of the College’s first study abroad program, in Grenoble, France. Lisa Smulyan ’76 attended in her junior spring and remembers that Smith had brought his family with him.

“He opened his tiny home to us, and we regularly congregated there for dinner, advice, and the experience of being part of the extended Smith family,” says Smulyan, the Henry C. and Charlotte Turner Professor of Educational Studies. “He would never tell you what to do, but his wry humor would help us see any complications of coping with a new culture in a different light. His friendship, warmth, and open-door policy continued when we returned to Swarthmore.”

Smith, who maintained an active correspondence with The Phoenix, was just as likely to submit an open letter to its pages as receive one in them, from faculty colleagues and students alike. He once penned a sonnet in which he equated the then-provost and president to two rival branches of the same royal family in 15th-century England: “Our York and Lancaster, as one enthroned, / Blest diarchy so doughty to defend / Gainst falling markets and the foe within …”

“Bernard could be pointed in his criticism but always attentive and often droll,” says Connie Hungerford, the Mari S. Michener Professor Emerita of Art History and Provost Emerita. “When he deemed a proposed general salary increase insufficient, he stood in a faculty meeting to quote from Oliver Twist: ‘Please sir, I want some more.’ Even the president cracked up.”

Smith retired in 1985 and returned to the U.K., where he settled in the tiny hamlet of Glascwm in a sparsely populated river valley in central Wales. The rural environment suited his non-21st-century sensibilities: He renovated an old coach house and sang in the local choir, gardened, traveled, and made furniture.

“He was a Renaissance man,” says Hungerford, one of many friends and former colleagues who trekked to Smith’s home for a must-see visit. “He loved sharing good food and wine; he delighted in music. He pursued research projects both in modern politics and on memorials in English churches to servicemen who had died in India, where he himself had been assigned.”

Indeed, Smith’s experience in India as a young man never left him. “There, he witnessed enough atrocity to permanently align his political thinking thereafter with reason, compromise, and unsentimental good sense,” says Phil Weinstein, the Alexander Griswold Cummins Professor Emeritus of English Literature.

In retirement, Smith also continued his translations and editions of treatises on 12th-century monastic life, issuing a revised edition of his first collaboration with Constable in 2003, and collaborating with him again on Three Treatises from Bec on the Nature of Monastic Life (2008). And he is the only emeritus faculty member to complete an additional B.A., while in his 80s, in classics, at the University of Wales.

“He understood the monks but was far from monkish,” Weinstein says. “Decades of Swarthmore students were marked by Bernard’s acerbic wit and penetrating asides; he all but bristled with a sense — at once playful and shrewd — of the complexity of things.”

In 1997, Smith spoke succinctly of his approach to life after Swarthmore: “The essential element of a happy retirement is to see it as a new life, not an epilogue.”

Twenty years earlier in The Phoenix, Smith expounded on life, both in and beyond the academy.

“If you don’t have fun, you can’t work,” he said. “You can’t spend all your time reading. Even the most devoted intellectual can’t do that,” lest they forget what they’re “being an intellectual for. ... We are committed to the intellectual life; this is what we do best. … But that doesn’t mean we have to be intellectuals 100% of the time. …

“Books are not an end to themselves. The study of history … is not an end to itself. The study of history ultimately ties in with the quest for self-knowledge or with an understanding of society. Whatever one may say the ends of education are, the ends of education are not education. Education always points to something beyond itself.”