In Honor of Emeritus Economics Professor Rob Hollister

President Valerie Smith shared the following message with the campus community on September 21, 2021:

Dear Friends,

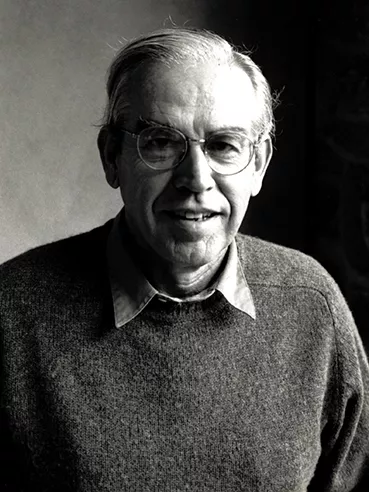

With deep sadness, I write to share the news that Robinson Gill Hollister Jr., the Joseph Wharton Professor Emeritus of Economics, died Tuesday, Sept. 14, in Needham, Mass., from complications from a fall. He was 86.

Rob, a member of Swarthmore’s faculty for 44 years, is remembered for balancing a distinguished research and teaching career with his pioneering work as a policy adviser to agencies and governments around the world. His outstanding contributions to scholarship and public policy have been a model of the impact the academy can have on the wider society.

Rob is survived by the artist Valerie Hollister, his wife of 57 years; his daughters Matissa and Arusha; and two grandchildren. A memorial will take place on Zoom on Saturday, Oct. 23, at 10 a.m; please contact m73hollis@yahoo.com for information. In lieu of flowers, please direct any gifts to the Robinson G. Hollister Summer Opportunity fund at gift.swarthmore.edu by choosing “other” and entering the fund name.

I invite you to read more below about Rob and his many contributions to our community.

Sincerely,

Val Smith

President

In Honor of Emeritus Economics Professor Rob Hollister

Robinson Gill Hollister Jr., the Joseph Wharton Professor Emeritus of Economics, died Tuesday, Sept. 14, at age 86. With his passing, Swarthmore has lost one of its most respected and influential community members. During a career devoted to the evaluation of public policies, his pioneering use and advocacy of randomized control trials created what is considered the gold standard for estimating the causal impact of social policy innovations.

“Rob Hollister was an institution in the Swarthmore Economics Department,” says Professor and Chair of Economics Amanda Bayer. “His colleagues and students will always remember him for his brilliant mind, quick wit, and big heart. He provided a wonderful model of how to use expertise in economics to help people.”

“For me, Rob will always be the exemplar of the liberal arts college professor,” says Professor of Economics Mark Kuperberg. “His wide-ranging interests and abilities set the standard for a well-rounded person.”

“For Rob, economics was not about theory but about using insights from economics to inform public policy so that it could improve people’s lives,” says Professor of Economics Ellen Magenheim. “This commitment was at the core of his teaching and all other aspects of his professional life.”

Hollister grew up in Glen Ridge, N.J., the only son of his parents’ four children. While he was in high school, he wrote an essay on agricultural subsidies that won a newspaper-sponsored contest. This experience sparked his interest in economics, which he chose as his major at Amherst College.

After graduating cum laude from Amherst in 1956, he taught briefly at Deerfield Academy in Massachusetts before pursuing graduate studies in economics at Stanford University. While a Fulbright Scholar at the University of London in 1961, he got his first exposure to economics applied to public policy. Although he then taught at Williams College for two years, his work and connections in London led to consultant assignments in Paris and Geneva. By the time Hollister earned his Ph.D. from Stanford in 1965, his international career in economics and public policy was already underway.

In 1966, Hollister joined the War on Poverty effort as a staff economist in the U.S. Office of Economic Opportunity, later becoming its chief of research and plans. Hollister headed the effort to design, implement, and analyze the New Jersey Negative Income Tax — the first large-scale social experiment using random assignment.

Random-assignment experiments are designed much like clinical drug trials in which some people get a new treatment and others get a placebo. In economics, a job-training program might be tested by randomly selecting some people to participate in the training while others do not, then tracking them over time to judge the efficacy of the program.

Although regarded warily in social policy circles decades ago, the random-assignment evaluation method has spread across many social science disciplines thanks in large part to Hollister’s use of the technique in a range of areas. He worked with the Ford Foundation in the 1970s, for example, on developing the National Supported Work Demonstration to test a direct-employment program for ex-addicts, ex-offenders, women on welfare, and low-income youth in 15 U.S. cities, including Philadelphia. Hollister served as co-principal investigator and said it was “one of the first realizations in social policy in which impact evaluation using random assignment produced results that were unexpected, and that underscored the value of rigorous evaluation for our learning about what works.”

“Rob was doing this work and advocating this methodology long before it was well-accepted in the profession,” says John Caskey, the Joseph Wharton Professor of Economics. “His persistence and logic won out.”

“To this day, every researcher who conducts a randomized control trial study in the social sciences owes a small debt to Rob Hollister whether they know it or not,” says longtime colleague Philip Jefferson, now vice president for academic affairs and dean of faculty at Davidson College.

Hollister once described randomized control trials as the “nectar of the gods — once you’ve had a taste of the pure stuff, it’s hard to settle for the flawed alternatives.”

Hollister joined Swarthmore’s faculty in 1971. For 44 years, he taught labor and social economics and econometrics, among other classes, to generations of students.

In 1977, Hollister co-founded the College’s public policy program, which for nearly 40 years provided students with internships and a senior thesis opportunity.

“His love of teaching wedded him to the College while his research accomplishments with studies of the negative income tax and urban poverty brought him national recognition,” says Raymond Hopkins, the Richter Professor Emeritus of Political Science. “If the College offered awards for ‘Renaissance Person,’ he would be the top contender.”

Kuperberg distinctly remembers an exchange he had with Hollister soon after his own arrival on campus in 1977. “Rob said to me that regression analysis was flawed in comparison to random experiments, and I had no idea what he was talking about because I had learned absolutely nothing about random experiments in graduate school,” he says. “To say that Rob was ahead of his time in terms of microeconometrics would be a severe understatement; he basically anticipated where the entire field was going.”

In 1977, Hollister co-founded the College’s public policy program, which for nearly 40 years provided students with internships and a senior thesis opportunity. “He viewed economic analysis as an instrument for the public good,” says Stephen O’Connell, the Gil and Frank Mustin Professor of Economics, “and helped to build a department that embodied that vision.”

“Rob had hundreds of valuable contacts in public policy research organizations and government agencies,” Caskey says. “He counseled students who shared his interest in policy issues, and he arranged post-Swarthmore jobs for so many I could not begin to count them. Many of these students went on to graduate studies in economics and public policy.”

As a rising junior, Assistant Professor of Economics Jennifer Peck ’05 got her first experience with economic and policy research after taking Hollister’s advice about a summer internship at Mathematica Policy Research, where he served as a senior fellow from 1971 to 1984 and whose first president was a former student. “I was so grateful for his generosity in making this connection,” she says. “It was a wonderful window into the impact research could have on policy.”

Hollister’s interests were capacious. “Over the years he supported diverse students' work, including efforts by majors in sociology, political science, and environmental studies, especially,” Hopkins says. “He encouraged innovative thought while grounding students in basic economics and statistics — skills that served public policy study extraordinarily well.”

Jefferson says Hollister’s mentorship of junior colleagues was just as meaningful. “As my research interests evolved towards economic poverty and income inequality, it was his encouragement, guidance, and endorsement of my work that gave me the support that I needed to have my voice heard,” he says. “I will always be grateful to him.”

“Rob was happiest when he could help people,” says Professor Emeritus of Physical Education and Sociology Michael Mullan, a longtime friend. “He was a man of considerable judgment, intellect, and warmth.”

Hollister also contributed vital perspectives to pressing issues on campus. Early in his tenure he studied the salary variance among male and female faculty members. During a strategic planning process in the 1990s when the student body stood at 1,450, he produced what came to be known as the Hollister Report, in which he concluded an increase of 200 students would be financially feasible. The College increased its enrollment in the 2010s and is currently at 1,650.

Hollister used his Swarthmore sabbaticals to travel and consult on a range of projects, ultimately working in more than 40 countries throughout his career.

Among his U.S. projects: From 1983 to 1985, he chaired the committee on youth employment programs of the National Academy of Sciences. He worked for the Rockefeller Foundation from 1984 to 1993 on an employment-training effort for minority single mothers. He chaired the advisory board for the evaluation of the Health Link Project, an intervention that attempted to help women and youth prisoners exiting the Rikers Island jail in New York City. He testified before Congress and was a member of the advisory boards of two U.S. Department of Labor programs — Youth Fair Chance and U.S. Job Corps. He wrote widely about the latter and said the evidence showed it was an effective program that provided social benefits that substantially exceeded the costs.

Among several dozen books and articles, Hollister is co-author of Labor Markets in Countries of the Near East: Operation Under Economic Restructuring (1994) and Labour Market Policy and Unemployment Insurance (1991).

While a self-described “random assignment fanatic,” Hollister also produced non- experimental work. In 1995, he and Caskey began a collaboration to assess the effects of a major community-development financial institution that required five years of extensive travel in the Mississippi Delta region. Together they built a database on the employment, wage, and benefit packages of firms in the institution’s loan portfolio and how they evolved over time; from that they made alternative estimates of jobs gained, retained, or lost.

For 44 years, Hollister taught labor and social economics and econometrics, among other classes, to generations of students.

“Rob’s research was never driven by ideology,” Caskey says. “He believed deeply in using empirical methods to assess the effect of various government programs or initiatives and letting the results speak for themselves.”

In 2006, Hollister became the second recipient of the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management’s Peter H. Rossi Award, which recognizes contributions to the theory and practice of program evaluation. Hollister was praised for his major contributions in the field: “In all cases, Rob’s work has been at the scientific frontier. It is also balanced and reflects his good judgment about where it is appropriate to devote substantial resources to program evaluation and where it is not.”

Hollister met his wife, Valerie, while they were students at Stanford. They regularly hosted salons in their Whittier Place home on campus.

“These events often ended with entertainment featuring songs with Rob on the piano and in full voice,” Jefferson says. “He was a person of many talents.”

“Rob loved to bring people together, both for dinner parties with friends from across the College on their iconic screened porch, and for fostering research collaborations within and outside the College with potential funders for research and between former students and current faculty,” Magenheim says. “He was really good at it, too. And he had a good intuition about what might help someone.”

In retirement, Hollister continued to share his love of music. He was well-known for his singing and harmonica playing and for participating with his grandchildren in an intergenerational community chorus.

When asked recently why he stayed at the College as long as he did, Hollister cited his colleagues and Swarthmore’s generous sabbaticals. But the main reason, he said, was the students: “We, the faculty, had a saying that the first rule was to ‘do no harm.’ We didn’t want to mess too much with the students and get them off track because they were good enough already.”

“It’s very hard to lose Rob,” O’Connell says, “but his legacy of rigorous economic analysis for the public good will remain at the center of our departmental aspirations and identity. He’s very much with us."