Answering the Call

Engineering students Jerry Gu '19, Kira Emmons '20, and Jasmine Charles '20 worked together over the summer to develop a hands-free system for Joshua Lorber.

It all started with a simple question.

Carr Everbach, chair of the engineering department, had been getting to know Joshua Lorber, an artist’s model with disabilities who longed for a way to get in touch with his family.

“When you want to talk to your dad,” Everbach asked, “what do you do?”

“I say ‘Dad,’” Joshua replied. “‘Call Dad.’”

So began a three-year process to develop a hands-free system with which Lorber could connect to his family with a single word. A student-led Swarthmore engineering team — later joined by a surprise member — intertwined the technical and the personal to make Joshua’s hope a reality.

“The ultimate satisfaction for an engineer is to get something to work and to get it into the hands of someone it can help,” says Everbach. “That’s our purpose, and it’s a great satisfaction to see that.”

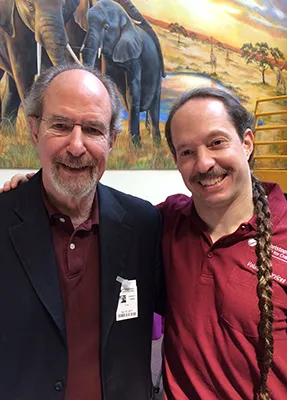

The system allows Joshua (right) to reach his father, Bennett Lorber '64 (left), with just a single word.

“This was a wonderful thing,” says Joshua’s dad, Bennett Lorber ’64, a renowned infectious disease expert who recently spent time with students in a chemistry seminar.

“I can’t tell you how comforting it’s been to know I can be out of the house and if Joshua needs me, he can call, and I can see how he’s doing,” says Lorber. “It’s been great. A brilliant thing.”

This story traces back 30 years. When he was 12, Joshua inexplicably started suffering from blindness, numbness in his hands, and short-term memory loss. Today, Joshua can’t use his hands to grip or squeeze things, and his family had worried for his safety when he was alone in their Cheltenham, Pa., home. They tested voice-activated technologies like Siri and Alexa, but none quite fit.

Then Lorber had the idea that customizing a system could be an interesting summer project for Swarthmore’s engineering students. That piqued Everbach’s interest.

The goal: a hands-free system with which Joshua could contact his mom, dad, or brother by name. The family member would get a text and call Joshua back on a special line connected to the home wifi, and their voice “would just magically appear in the room,” says Everbach.

Achieving that, though, was arduous — “a process of continual refinement of the design,” he says. The team’s Raspberry Pi computer was hacked, and the system hardware failed the first time they tried installing it, says Jerry Gu ’19, an engineering student from Ellicott City, Md., who joined the project unsure of his technical prowess, but who ultimately developed the first circuit to work after several attempts by students over the years.

“There were definitely weeks where I felt I wasn’t making the type of progress I wanted to,” adds Jasmine Charles ’20, of Princeton, N.J.

The technology could have even wider application for people with dementia or those with particular disabilities.

But there were also moments of fortuitousness. Pierce Forte, now a senior at Blair Academy in Chester, N.J., emailed Everbach to express interest in an engineering project and became a critical component of the team. He wrote the base code for the system and solved the quandary over how to sync it to the microphone.

“He really got the project going,” says Everbach. “It’s an example of how the more perspectives you have, the more people contributing in different ways, the more likely you are to succeed.”

Kira Emmons ’20, a computer science and engineering major from Fairfax, Va., helped put the finishing touches on the voice recognition system, known as Snowboy. She viewed the project as an opportunity to build on her classwork while making a difference.

“As students we go into summer research just hoping we can gain new skills,” she says. “But it’s extra nice to be able to turn out a finished product that someone can actually use.”

Despite the hiccups, fits, and starts, the students remained confident that their hard work would pay off. Their reward came when they went to the Lorbers’ home to install it last spring.

“I’ll never forget how excited Joshua was,” remembers Gu. “He laughed when we played back his voice, and when we finally got the system to work, he gave me this tremendous hug.”

“Working with the students and [Everbach] was a great experience for Joshua,” adds Lorber. “They really stuck with this, always excited and animated about the project and just wonderful with Joshua.”

“The ultimate satisfaction for an engineer is to get something to work and to get it into the hands of someone it can help,” says Everbach.

The system sits on a shelf outside Joshua’s room, in a small cardboard box filled with electronic equipment. It connects to the microphone and a wire reaching to a device in the ceiling. There’s still the occasional glitch, Lorber says, but the system is working well, offering invaluable peace of mind.

“It’s great for Joshua to be able to reach me when he wants to talk, and vice versa, which is now more important than ever,” Lorber says, with the recent loss of his wife, Carol Finneburgh Lorber '63.

For Everbach, this was a project in which students gained hands-on experience while providing a service to the community.

“There’s a happy customer, and we all get to feel good about what we accomplished,” he says.

But he also takes a longer view. What if there was a wearable version of the system that Joshua could use outside the house? What if the team could become a developer for Amazon’s Alexa technology, providing them with programming tools “to allow us to go under the hood” and tailor it to individual clients?

“This could be useful for a much wider range of people, whether it’s people with dementia or those with particular disabilities,” Everbach says. “I don’t know that this story ends with Joshua.”