A Summer Brimming With Ingenuity

To conduct research on wind tunnels this summer, students zoomed with Professor of Engineering Carr Everbach (pictured), who sometimes had to shout over noise as he entered commands for the tunnel on a computer in another room.

Though the pandemic forced much of the world into lockdown and kept Swarthmore community members from collaborating on campus, it could not stop nearly 400 students — roughly a quarter of the student body — from participating in College-sponsored research this summer.

To do so, students enhanced their adaptability, trading travel for research conducted from home, and using Zoom to connect with teammates and advisers across the distance — and, sometimes, multiple time zones.

The result was a summer brimming with ingenuity, much of which was on full display during the annual Summer Research Showcase, hosted by the Swarthmore Libraries in July. Held virtually this year instead of as a traditional pizza lunch, the showcase succeeded in celebrating the students’ work, with nearly 60 community members attending remotely to watch the participants’ lightning presentations.

“Every single year I’m just stunned by the students,” says Science Librarian Andrea Baruzzi, who coordinated the event with Digital Scholarship Librarian Nabil Kashyap.

Below is a snapshot of four innovative projects to which students devoted their time this summer with the help of College funding:

Fouad Dakwar ’22: “In Vitro: A Rock Opera”

Fouad Dakwar ’22 had planned to stage a performance of his original rock opera at a New York theater in August, but instead he is releasing it as an album on all major streaming platforms.

In what was likely the Summer Research Showcase’s most unorthodox presentation, Fouad Dakwar ’22 played the high-energy opening song of In Vitro: A Rock Opera, the original work he is writing on a Ken Guilmartin ’67 grant from the Department of Music & Dance. The opera tells the story of a Black woman and a Palestinian man who use gene-editing technology to make their baby white, hoping to grant him white privilege and protect him from racism.

An honors music and theater special major from New York, N.Y., Dakwar had the idea for the work on a subway ride four years ago, when he read about a doctor who was sentenced to prison for performing the world’s first gene-editing operation on twins at risk of contracting HIV.

“That led me down the Black Mirror route,” says Dakwar, referring to the dystopian Netflix series. “It hit me that sci-fi shows tackling future technology are often very ‘race-neutral’ when, in reality, technological advancements are most often used by the state to extend white supremacy and xenophobia.”

Dakwar had planned to stage a performance at a New York theater in August, but as a result of COVID-19, he instead is releasing the opera as an album on all major streaming platforms. The project is also funded in part by Eat at the Table Theatre Company’s co-founder and co-executive director, Emma Morgan-Bennett ’20, with Moses Rubin ’19 producing, Max Barry ’19 serving as the production’s drummer, and Galek Yangzom '22 illustrating album cover art. With money from his stipend, Dakwar has been able to provide recording equipment and to pay the actors for their work.

The shift to an album format has had its benefits: Beyond offering an opportunity to learn the ins and outs of studio recording, Dakwar says, the digital format will also make the ideas from Black writers and race theorists that he has incorporated more accessible to a wider audience.

The pandemic changed his project in another way, too: He’s more grateful for the opportunity he has.

“I’m mainly just thankful to the music department for letting me work on it for a summer, especially one in which racial justice and solidarity work has been so significant,” he says. “I'm literally doing my dream job right now, and I don’t have to worry about funding it myself. I’m really lucky.”

Grace Sewell ’22: “Reimagining Soviet Jews: Representations of the Jewish Autonomous Region in the USSR and Abroad”

Birobidzhan, designated by the Bolshevik government as the Jewish Autonomous Region in 1934, has fascinated Grace Sewell ’22 since high school, when she learned it was a “sister city” of Beaverton, Ore., near her hometown of Salem.

You’ve heard of Israel, but you may not have heard of the world’s first Jewish state: Birobidzhan.

Sitting at the border of Russia and China, Birobidzhan was designated by the Bolshevik government as the Jewish Autonomous Region in 1934, making “Jewish” an official Soviet nationality. Many Jews resettled to the region in hopes of escaping persecution. However, despite decades of financial support from Jewish groups in the U.S., Argentina, and other countries, the region’s hostile climate and land conditions eventually forced most Jews to leave.

Birobidzhan has fascinated Grace Sewell ’22 since high school, when she learned it was a “sister city” of Beaverton, Ore., near her hometown of Salem. Now an honors Russian and Spanish double major at Swarthmore, Sewell won a Eugene M. Lang Independent Research Grant from the Humanities Division to study the region from home this summer.

“Birobidzhan is very much an imaginary place in terms of how it was constructed from the beginning,” Sewell says. “Nobody ever seemed to agree on anything that it was supposed to represent, but at the same time it continued to garner so much support, even through its failures and the terrible things that happened there.”

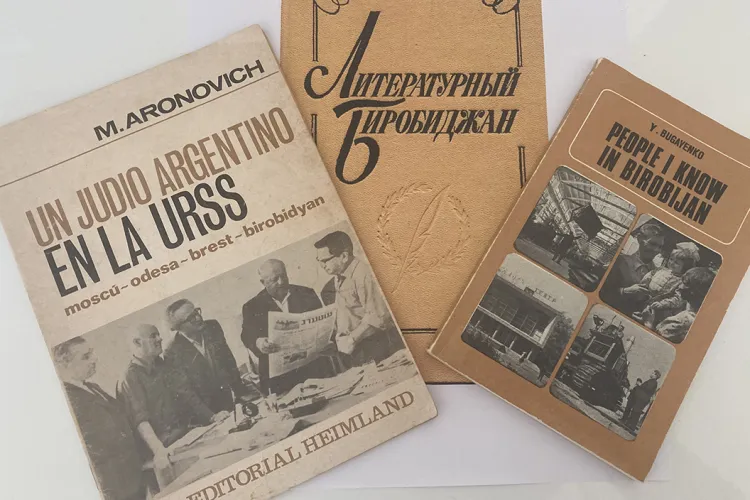

Sewell is more interested in what Birobidzhan did than what it failed to do. By studying relics as varied as Soviet propaganda posters and the memoirs of Argentinian Jews who moved to the region, Sewell has discovered the symbolic resonance that Birobidzhan had for its residents and for Jewish people around the world.

For Sewell, the project has “definitely made me have a deeper connection to and understanding of my own family's history,” she says, “as well as the histories and stories of all these people who had had so many dreams and so many disappointments related to this project.”

Josh Vandervelde ’23, Daniel Curtis ’21, and Professor Carr Everbach: “The Swarthmore Wind Tunnel”

To aid with their research, soldering equipment and other supplies were sent to Daniel Curtis ’21 in Macomb, Ill., and Josh Vandervelde ’23 in El Cerrito, Calif.

One research group calibrated the speed and measurements of a high-speed wind tunnel, constructed a pressure sensor array with a custom circuit board, 3D-printed an aerodynamic lift body, and engineered a system to track movement patterns — all without ever meeting in person.

The group, composed of Josh Vandervelde ’23, Daniel Curtis ’21, and Professor of Engineering Carr Everbach, studied Swarthmore’s new wind tunnel, a 45-foot-long tube structure in Maxine Frank Singer Hall that allows students to extrapolate how aerodynamic bodies would fare in high-altitude flight. Funded by a Richard Hurd ’48 grant, their work this summer lays the groundwork for future student projects, while also furthering the research started by Quentin Millette ’20 on kites that generate renewable energy from powerful, high-altitude winds.

Making the project work remotely wasn’t easy: Everbach would Zoom the students from the lab, sometimes having to shout over the wind’s noise as he entered commands for the tunnel on a computer in another room. In order for the group to assemble and test their tools at home, administrative coordinator Cassy Burnett mailed soldering equipment and other supplies to Curtis in Macomb, Ill., and Vandervelde in El Cerrito, Calif.

“Even though we were separated, and it wasn’t in ideal conditions, I definitely learned a lot about the processes of team engineering,” says Vandervelde, and about “how many things can go wrong in a project, and just picking yourself up and continuing to go forward.”

Adds Everbach: “Engineering is all about the habits of mind, the meta issues — when something isn't working, what do you do? How do you proceed? Those were the real important lessons learned this summer.”

Jake Chanenson ’21: “Investigating Ethical Risk in AI Literature”

“A machine-learning algorithm doesn’t create inequity, it perpetuates it,” says Jake Chanenson '21, who looked at the ethical risks that come with technology. “So to try and apply a technological fix to a social ill is not the way forward.”

For as long as he can remember, Jake Chanenson ’21, a computer science major and math and linguistics minor from Philadelphia, Pa., has been interested in the intersection of technology and the humanities — particularly issues surrounding data privacy, digital rights, and digital ethics. He cites Cory Doctorow, who spoke at the College in 2018, as a major influence on his life.

But the more Chanenson has thought about tech ethics, the more he’s also thought about tech policy — or the lack thereof. Tech companies often escape consequences for their misdeeds, he says, citing such cases as Amazon’s use of an artificial intelligence recruiting tool that discriminated against women.

Backed by a Social Impact Summer Scholarship from the Lang Center for Civic & Social Responsibility, Chanenson had planned to evaluate the ethics of autonomous vehicle algorithms this summer at McGill University’s Responsible Autonomy & Intelligent System Ethics (RAISE) Lab. The new interdisciplinary lab aims to make intelligent machines operate as responsibly as possible.

However, with COVID-19 preventing his move to Montreal, Chanenson instead dug into AI literature from home to see how researchers and industry leaders are thinking about the ethical risks that come with technology. Although many researchers are interested in issues of fairness, bias, and privacy, he says, not as many are concerned about non-malfeasance, or about the ability of AI to displace human workers.

“Figuring out what the problems are is really easy; finding good solutions is really hard,” he says. “A machine-learning algorithm doesn’t create inequity, it perpetuates it. So to try and apply a technological fix to a social ill is not the way forward.”

Perhaps someday Chanenson will be the one developing those solutions, as he’s now considering working in policy after graduate school. “What this [internship] helped me do,” he says, “is it gave me that perspective on possibilities outside of academia.”