A Life of the Mind

“I blame Swarthmore for ruining my dream of being a corporate lawyer making lots of money, and sometimes for not being able to sleep at night,” says St. Julian-Varnon. “But I wouldn’t want it any other way.”

Earlier this year, the teacher one classroom over called out to Kimberly St. Julian-Varnon ’12: “Hey, will you come talk to this kid?”

The student wanted to drop out because he was making $25 per hour and his family needed every bit of it.

“I get that,” she told him, “but when you’re 25 with no diploma, things will look different. If you finish, you can get a small-business loan, maybe start your own company.”

After mulling it over, he decided to enroll in night school.

“That child no longer has to decide between a future and a paycheck,” says St. Julian-Varnon, a scholar of Slavic studies with a bachelor’s from Swarthmore and a master’s from Harvard who returned to her high school alma mater in Dayton, Texas—population 7,734—to teach history.

Then there’s the dyslexic boy whose parents told him he’d be lucky to work at McDonald’s, for whom St. Julian-Varnon built a college plan and found scholarships. And the AP student with the photographic memory who was going to settle for a job at the plant but, after St. Julian-Varnon’s encouragement, applied and was accepted to Texas A&M for mechanical engineering. And the Latino kids who came up to St. Julian-Varnon the day after the 2016 presidential election, one with puffy eyes, afraid they would be deported.

“Episodes like that,” she says, “are why I do this.”

She knows these kids because she was that kid. Literally. St. Julian-Varnon sees students sitting in the same desks she did, reading from the same books, and, just as she once did, struggling to fill in the blanks of their future.

She will eventually return to the academy for her Ph.D. But not, as she once aspired, to write the most acclaimed books in her field. Now, she wants to educate lower-income communities to enrich and empower them.

“I’m living the life of the mind, learning every day,” she says. “But if I’m not teaching other people how to do it, not living in service of others, I’ve not only betrayed myself, I feel like I’ve let down my Swarthmore community. And I’ve worked entirely too hard for that.”

...

St. Julian-Varnon went on to earn a master’s from Harvard in Russian, Eastern European, and Central Asian studies. A Ph.D. program and tenure-track position beckoned, but she felt pulled in another direction.

She wanted to clear her head, and also to be on the ground, sharing her passion for history with the type of student she had been.

“I’m living the life of the mind, learning every day,” she says. “But if I’m not teaching other people how to do it, not living in service of others, I’ve not only betrayed myself, I feel like I’ve let down my Swarthmore community. And I’ve worked entirely too hard for that.

So, four years ago, she returned to Dayton to teach seventh- to 12th-grade history. Some things had changed; with a weaker local economy, students had more anxiety and responsibility. But most had not; there remained that milieu of I’m from Dayton, don’t expect much from me.

“It’s my job to change that line of thinking,” she says.

St. Julian-Varnon teaches students whose parents are in prison, or going through rehab. At her other job, teaching history at Lee College in nearby Baytown, she has students who bring toddlers to class as well as students in their 60s. But her message doesn’t waver.

“These doubts you might have, these negative things you might be hearing from others, well, I thought and heard the same things,” she says. “But you can transcend them.”

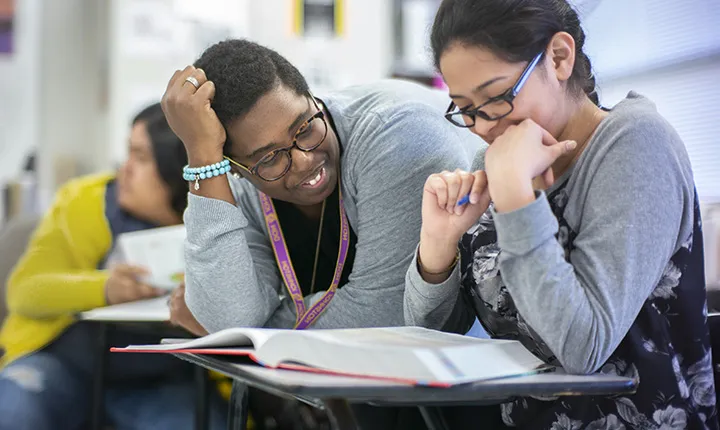

St. Julian-Varnon runs a laid-back classroom, but she doesn’t take excuses—especially from her advanced high schoolers, most of whom are used to coasting to A’s.

“Then they get to me and they’re getting pushed and they want to quit,” she says. “But I won’t have it. They have to put their all into it with me.”

Almost every day, a student asks St. Julian-Varnon why she came back to Dayton. At first, she wasn’t sure how to respond.

“Well, I think you deserve a good education,” she says. “Why don’t you think you deserve a good teacher?”

On good days, her students are locked in, making connections between lessons and subjects. They’re calling each other out for not backing arguments with evidence.

“You can actually see the learning happening,” St. Julian-Varnon says. “The brains firing off.”

And every once in a while, she gets to see the impact she’s making on someone’s future.

She returned to Swarthmore in the fall as one of the Aydelotte Foundation’s inaugural Frank 5 Fellows and shared stories from the classroom. Among them, the boy with the lucrative job who decided to stay for the diploma.

A few weeks later, the boy watched a video of the speech in his Dayton classroom. His teacher, Bret Alldredge—the one who had asked St. Julian-Varnon to speak to the young man, and the one she had gone to as a student for guidance—had put it on.

She peeked into the classroom and saw tears in the boy’s eyes.

“Then the bell rang, and he came up to me and just said, ‘Thank you,’” she says. “I told him, ‘You owe me a diploma,’ and he looked up at me and said, ‘You’re gonna get it.’”

Read more "A Life of the Mind" in The Bulletin.