From Theater to Thriller: The Evolution of Horror Television

Essay by Ellie Tsapatsaris '24 for Television Studies Course

Audiences have always been drawn to the horrific. However, despite this natural pull, what is deemed “scary” is constantly evolving. The medium of television is no exception to this evolution. As time has gone on and TV has become an increasingly important mode of communication, shows within the medium have adapted in response to its increasing prevalence. In the following pages, I plan to exact a close analysis of two television shows within the broader horror genre. Specifically, I will focus on how horror television has evolved over time while noting how elements of the national climate during those time periods might have contributed to the shift. Through an analysis of form and narrative, and using the shows The Twilight Zone (CBS 1959-1964) and Severance (Apple TV+ 2022- ) as examples, I hope to indicate and explain key differences between horror TV in different time periods.

The Twilight Zone is a notable cult classic, especially within the realm of horror television. Each episode of the anthology series presents a new, horrific narrative complete with unique actors, characters, and settings. Spanning five seasons with a total of 156 episodes, the show at large has made an immeasurable impact on popular culture to this day. Countless pieces of horror media allude to The Twilight Zone episodes, and the show has garnered a number of spinoffs, including Jordan Peele’s The Twilight Zone (CBS 2019-2020). Formally, many horror series follow The Twilight Zone’s discrete episodic format: Black Mirror (Netflix 2011- ) tells a different narrative every episode, while American Horror Story (FX 2011- ) delves into a new story each season. Outside of film, television, and the horror games that followed, The Twilight Zone has thrilled fans in physical ways as well: for example, Disney’s Hollywood Studios features a ride called “The Twilight Zone Tower of Terror.” Clearly, the show has maintained importance in the minds of horror creators, fans, and critics, even 60 years after it first aired.

Severance, created for Apple TV, aired in 2022. It puts a chilling spin on the concept of work-life balance. The show follows a major tech company called Lumon Industries and highlights its unique business model. This model relies on a neurological procedure called “severance” which causes the subject being “severed” to gain split consciousness. Each severed employee has an “innie” persona and an “outie” persona, which corresponds to themselves at work and at home, respectively. As a show, Severance deals with issues of ethics, grief, and labor. Despite its recent release, it has already been greenlit for a second season and is the topic of scholarly articles that dig into the psychological considerations brought forth by the show’s form and implied messages.

To aid in the historical positioning of both of the shows to be analyzed, it is important to consult film scholars and their works. Jon Kraszewski’s 2008 publication titled “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Twilight” considers The Twilight Zone creator Rod Serling as an auteur, and outlines how his writing and subsequent practices went against what was typical of TV production in 1960s America. Kaszewski cites historians in their agreement that The Twilight Zone defines Serling’s switch from relatively literal plotlines to the more metaphorical narratives which define modern horror (Kraszewski 2008, 343). Additionally, he argues that each of the show’s episodes reacted to pertinent historical trauma contemporary to their release. These issues included, but were not limited to, McCarthyism, civil rights struggles, fame, prejudice, and corporate culture (Kraszewski 2008, 343). Because of its discrete anthology format, The Twilight Zone could tackle a plethora of socially relevant themes each season.

In his explanation of anthology scripts, Kaszewski maintains that although they allow for experimentation and variation within the series, they can also constrain the genre in some ways (Kraszewski 2008, 347). One reason for this constraint might be lack of significant development. Most episodes in The Twilight Zone feature a runtime of approximately 25 minutes – by today’s horror standards, this feels entirely too short to foster a fully realized and thrilling plot. Kraszewski brings attention to this issue by noting that unlike modern horror, and because of their discrete format, many episodes from The Twilight Zone seem to favor character development over action (Kraszewski 2008, 350). Contemporary anthology shows such as American Horror Story and Black Mirror remedy this in some way, with American Horror Story taking a full season to develop a plotline, and Black Mirror featuring significantly longer episodes which average a bit over an hour.

It is also notable to mention that horror television began as a much more theatrical and straightforward genre than it now is. In fact, the discrete anthology approach to television was actually modeled on theatrical writing. Historically, this artistic crossover makes sense: after the second World War, the theater industry tanked, causing its personnel to scramble for new jobs (Kraszewski 2008, 345). As television was an up and coming industry, it felt natural for displaced theater makers to settle within that realm, bringing a theatrical approach to storytelling with them into the TV industry (Kraszewski 2008, 346).

Returning to The Twilight Zone and Severance as case studies, one way that viewers can clearly see theater’s influence on older horror and its relative irrelevance in modern horror is through episodic segmentation. In focusing on the second episode of each show’s first season, it is immediately clear through the scene breakdown (See Appendix) that Severance features a lot more scenes (34, not including title sequence/credits), with less happening narratively per scene, whereas The Twilight Zone has far fewer scenes (7, not including title sequence/credits) with more happening per scene. Not at all dissimilar to a play and its formatted acts, The Twilight Zone is limited in its set and remains stationary in one, proscenium-coded frame while the narrative rushes to unfold within it.

Another way that The Twilight Zone alludes to its theatrical roots is through its pointed reflexivity. Each episode starts with director Rod Serling himself explaining to the viewers what they are about to see: in a way, he acts as a one-man Greek chorus. At the end, he reappears to convince them to tune in next week. These scenes, which bookend the episode, are a clear acknowledgement of TV as a medium as well as the mechanics of it. They add an air of reality that echoes that of live performance. More specifically, during the exposition of “Mr. Denton on Doomsday,” Serling narrates the following: “This is the third principal character of our story. Its function, perhaps to give Al Denton his second chance” (03:48-03:56). Again, the show is aware of its own medium and the audience’s proximity–in that way, it is not unlike theater. The Twilight Zone is also often observational. Every week, as the camera in the title sequence descends to the diegetic world and the fog clears, the viewer is invited to peek into the seemingly isolated social experiment that is “The Twilight Zone.” While the screen acts as a barrier between viewer and viewed, the show’s realistic aspects remind the audience that horror is closer–or, in terms of theater, more live–than we might initially think.

Similarly to Kraszewski’s article, George Gerbner and Larry Gross’s “The Scary World of TV's Heavy Viewer” from the book Popular Culture: Mirror of American Life also offers insight into The Twilight Zone’s effect on modern horror: this time, in a more temporal way. Written in 1977, the article reflects scholarly sentiments on the series just 13 years after its conclusion. Taken as a primary source of evidence outlining the sentiment of media scholars in the 1970s and their views towards horror, it is clear that these authors view violent horror as a threat to society. Broadly, Gerbner and Gross’s chapter outlines the dangers of violent television. The authors urge viewers to be wary of violence in media not only because it “stimulates viewers to violent or aggressive acts” (Gerbner & Gross 1977, 123), but primarily because it depicts harmful power dynamics as a social reality that we have no choice but to live with. Focusing on the universality of fear, the authors note its exploitability and state that TV violence promotes exaggerated assumptions about the real world. Gerbner and Gross even go so far as to suggest that, because violent media often takes place in urban settings, it could lead to an emigration of middle class citizens from cities (Gerbner & Gross 1977, 123-124).

Gerbner and Gross repeatedly emphasize the rapidly growing influence of TV on American society–with a specific focus on American youth–in an attempt to prove just how dangerous of a tool TV can be. In their words, the average 1977 viewer is different from their older counterparts in that they have grown up with TV and are thus innately dependent on it (Gerbner & Gross 1977, 124). The initial distrust of TV by Gerbner, Gross, and other scholars contemporary to The Twilight Zone could explain why early horror TV was relatively tame in comparison to the psychologically and physically chilling genre that we are used to in 2023.

Another article that offers scholarly input on the evolution of horror as it pertains to the two analyzed shows is Bethan Ackerley’s “Work-Life Balance?,” published in 2022 by New Scientist. This contemporary article argues that Severance acts as a portrait of the working world. Coming off of a time riddled with war, fantastical television shows of the 1960s often challenged postwar notions of families by creating “critical distance” (Kraszewski 2008, 350)–by mixing social verisimilitude with the incredible, viewers are able to confront important social conventions in a non-invasive, personally removed manner. Similarly to Kraszewski, Ackerley also cites viewer relationship to the text. She states: “Even the devil’s bargain of severance is just an extreme version of what many employees already do: leave your personal life at the door, do what you are told to and, above all, be grateful” (Ackerley 2022, 32). Again, especially because of TV’s ever-increasing pertinence, an argument is made for viewers seeing themselves within the fantastical and being able to interact with personal issues in a supernatural way.

Ackerley also makes sure to specify that Severance is not without allusions to classic horror. She notes that the Lumon Industries building resembles “a corporate version of the Overlook Hotel from The Shining” (Ackerley 2022, 32). Even as the genre of horror has evolved, it still refers back to itself: The Twilight Zone, The Shining, and other horrific classics will continue to inform the new generation of horror throughout its evolution.

Finally, Ackerley expresses disdain over the fact that Severance does not explore the pandemic’s effect on work, despite it being filmed in 2020 and 2021. Spearheaded by influential shows like The Twilight Zone, this outlines not only the wish, but the expectation that contemporary film scholars have for horror media to attack socially relevant issues as part of their horror.

As the medium of TV became less novel and horror as a genre started to gain more traction, TV producers gained more trust in the viewer to be able to decode important and timely narrative themes without the need for overt theatricality. As an example of viewer distrust amidst the medium’s early stages, The Twilight Zone’s “The Sixteen-Millimeter Shrine” follows aging movie star Barbara (Ida Lupino) as she spends her days drinking, skipping sleep, and nostalgically watching the movies she had once starred in. This episode is interesting in that it begins with a picture-in-picture as we, the audience, watch one of Barbara’s old films along with her. The unconventional shot, however, doesn’t linger for long–it soon switches to an establishing shot of Barbara watching the tape, complete with Rod Serling’s narration to make what we are viewing abundantly clear. In fact, Serling literally narrates the following: “picture of a woman looking at a picture” (01:07-01:10). The rest of the episode features continuity editing, over the shoulder shots, shot-reaction shots, and establishing full body shots when characters enter rooms. In a glaringly conventional way, the camera follows whoever is speaking. The episode follows a single-camera mode of editing, and overall, is very typical of classic Hollywood. Serling leaves almost no room for the viewer to misinterpret his vision, and everything about the composition of the episode is straightforward.

Severance, on the other hand, doesn’t quite hold the viewer’s hand in the same way. Modern development of technology certainly helps with this, especially when considering the phenomenon of transmedia viewer interaction. Severance fans can easily interact with the text through sources beyond TV: they can tweet about their favorite episode, interact with actors’ profiles online, or even consult a Severance Subreddit thread to share analytical space with other fans. For example, the map of Lumon Headquarters that shows up in Severance episode “The You You Are” notably appeared on Reddit following the episode’s release as it “quickly became the object of intense fan speculation” (Collier). This viewer interaction, which is unique to modern media, implies a closeness that is specifically noteworthy in its relationship to horror texts. Here, the horrific other can exist in the viewer’s phone: something that they carry with them everywhere and rarely ever escape.

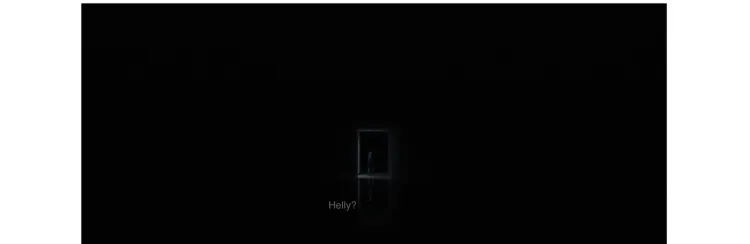

The development from the more theatrical performances present in The Twilight Zone to the increasingly abstract and socially conscious narratives in Severance is also aided by formal elements that both support and invite psychological analysis. Again, Severance’s “The You You Are” begins with a trigger warning and a flashing light sensitivity warning. Then, we only hear audio before cutting to a slow pan out of a reflection. Soon, the camera begins to focus on small but crucial details: the bloody gauze on “innie” Helly’s (Britt Lower) wrist, a clock to show the passing time, Helly’s eyes to indicate exhaustion, etc. The framing of these shots is uncomfortably close–just as Helly is stuck in her severed state, we are trapped along with her. There is no establishing shot here. Albeit different from classic Hollywood editing, the absence of an establishing shot makes sense: unlike The Twilight Zone’s discrete format, and given the sequential nature of the show (and its bingeability as is almost encouraged via its streamable format) the audience doesn’t actually need assistance reintegrating into Severance’s diegetic world.

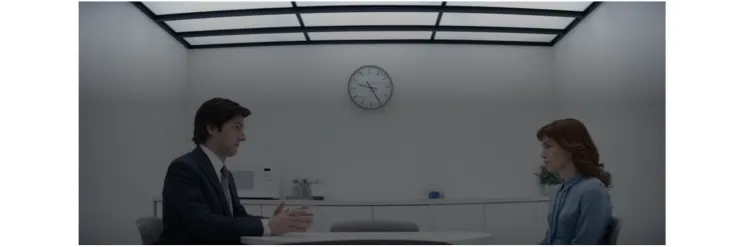

Additionally, throughout the episode, there is a recurrence of focused, panning shots as various characters walk through sterile hallways. However, in these many walking sequences, the editing is not necessarily continuous–a character will turn one way and the next cut will show them emerging from the opposite direction. In Severance’s dystopian world, this editing helps reinforce a feeling of disorientation. In terms of portraying conversations and interactions between characters, the cinematographer uses long shots to create distance and closeups to build tension. This indicates that while there is clearly a distance between the “innies” and “outies,” the two worlds are closer than what they and we might initially think. Additionally, shots of conversations are usually flat on, with all two or three characters speaking towards the camera, on the same plane. This two-dimensionality paints Lumon’s severed floor as a stripped-down reality.

When scenes take place outside of Lumon’s “severed” floor, however, the editing is much more continuous and conventional. These scenes often start with an establishing shot. Shots follow the 180 degree rule, are relatively continuous, and are overall more conventional. As viewers, we recognize parallel editing to build tension. The clear difference in editing style and continuity between the two worlds is an indication of the diegetic divide between the locations.

Another notable aspect of form that encourages viewer analysis is the mise-en-scène of Lumon’s severed floor workspace. A constant across all Severance episodes, it is clear that there is something unrealistic and uncanny about this space. Lumon’s stark, white walls are sterile, and the smartly dressed employees stand out consciously against the glaring background. There is a distinct disconnect between the color palette of the people and the place, just as there is a disparity in access to information between the Lumon employees and their employers.

Still from Severance S1 E5: “The Grim Barbarity of Optics and Design”

However, in a scene from “The Grim Barbarity of Optics and Design” where Mark (Adam Scott) and Helly begin to question the ethics of Lumon’s agenda, this relatively stagnant mise-en-scène is challenged: the employees are instead set against a darker background. In the context of Mark and Helly’s newfound information, this shift serves to indicate a closing gap between employee and employer knowledge.

Still from Severance S1 E5: “The Grim Barbarity of Optics and Design”

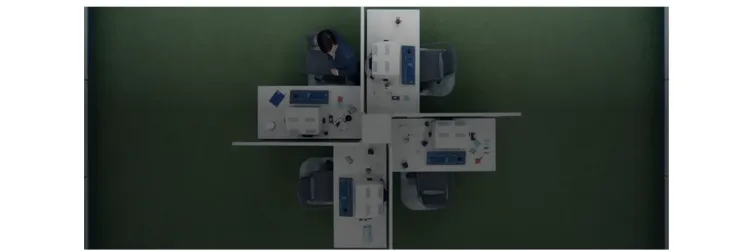

The architecture of the space–as well as how said architecture is framed by the camera–also creates meaning within the context of the episode. Namely, when Mark smuggles a book into his jacket pocket so that he can illegally read it, the camera sits in a bird’s eye view above the cubicles.

Still from Severance S1 E5: “The Grim Barbarity of Optics and Design”

First and foremost, the birds-eye shot evokes feelings of surveillance. It is no secret that Mark and the other employees are consciously being watched by their bosses. Also, from this view, the cubicles almost look like a puzzle or maze: a maze which traps the Lumon employees within their severed lifestyle. Like the exit of a maze, details about Lumon’s actual intentions are notably difficult to find–however, once found, they open up a massive bank of information.

After initially leaning on its theatrical roots, it is clear that TV within the horror genre has evolved into something more open to interpretation. Because of increased trust in the TV viewer, and especially with the advent of interactive transmedia texts that close the gap between the monstrous “other” and the TV audience, modern horror is scarier than ever. Now, producers are able to create more formally challenging texts with the understanding that viewers have the resources to decode them. As media consumers become increasingly comfortable in their consumption and technology continues to grow, so will the genre.

Appendix

S1E2 Scene Breakdowns: Severance and The Twilight Zone: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1ZIqIFkzbcQFIV8KltNK4swQbnuA1U5PNoMM…

Works Cited

Ackerley, Bethan. “Work-Life Balance?” New Scientist, vol. 253, no. 3375, 2022, p. 32. Science Direct, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0262-4079(22)00338-4. Accessed 3 April 2023.

Collier, Madeliene. ““Unknown, Unknown, Delaware, Unknown”: The Mind-Games of “Severance.”” New Review of Film & Television Studies, https://nrftsjournal.org/severance/.

Gerbner, George, and Larry Gross. “The Scary World of TV's Heavy Viewer.” Popular Culture: Mirror of American Life, Del Mar, CA, 1977, pp. 123 - 127. UPenn's George Gerbner Archive, https://web.asc.upenn.edu/gerbner/Asset.aspx?assetID=285.

Kraszewski, Jon. “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Twilight: Rod Serling's Challenge to 1960s' Television Production.” New Review of Film and Television Studies, 2008, pp. 343-364. Taylor & Francis Group, https://doi.org/10.1080/17400300802424899. Accessed 20 March 2023.

Serling, Rod, producer. The Twilight Zone. 1959. Paramount Plus.

Stiller, Ben, and Aoife McArdle, producers. Severance. 2022. Apple TV.