The Politics of Yesterday Girl

Essay by Isabelle Titcomb '22 for German Cinema Course

In the wake of the French New Wave and the rise of arthouse cinema, young German filmmakers sought to differentiate themselves from the older generation of filmmakers, who they blamed for their work under the Third Reich. In 1962, the young filmmakers wrote the “The Oberhausen Manifesto,” in which they claimed that the end of the Third Reich has presented the film industry with “new freedoms,” and that “The old film is dead. We believe in the new one.” (Rentschler, 202). However, the method by which these New German filmmakers would achieve a New German Cinema was left to be desired. While New German Cinema filmmakers tended to vary stylistically, they prioritized art and intellectualism over commercial success. Alexander Kluge was one of the twenty-six male filmmakers who signed the Manifesto. Kluge’s first feature film was Abschied von gestern (1966) also known as Yesterday Girl, which was based on his short story “Anita G.” The film is about Anita (Alexandra Kluge), a young Jewish woman from East Germany trying to find her way in West German society after being found guilty of petty theft. The film includes few intertitles, which are reminiscent of silent film and liken Yesterday Girl to the chamber dramas of the early twentieth century. One well-known chamber film, The Last Laugh (1924), asks, “One day you are preeminent, respected by all...a minister, a general, maybe even a prince. But, what will you be tomorrow?!” while Yesterday Girl asks, “Will yesterday come tomorrow?” Like the doorman in The Last Laugh, there is no place for Anita in society. Yesterday Girl is a departure from past German cinema due to its political underpinnings, but it stops short of feminism.

In portraying Anita, doubly marked by Otherness as both Jewish and a woman, Yesterday Girl tackles the burden of representation. Thomas Elsaesser points out the risk of fetishizing the token Jew in post-war cinema or bringing to life too much that it betrays the representation altogether. In his essay “New German Cinema and History: The Case of Alexander Kluge” Elsaesser posits that the absence of consequences of the Holocaust in New German Cinema is a necessary step in the mourning process. Unlike the standard mourning process, in which one may mourn the object, detach from the object, and let go, Germans are unable to mourn for their dead. Thus, they are situated in a new mourning step, termed “presence as parapraxis” (Elsaesser, 410). This presence as parapraxis manifested itself in efforts that resulted in “unexpected or unwanted” results (Ibid). The Holocaust is present in Kluge’s work, but rather than representing it directly, his work focused on what, better who, repressed it from the collective memory. Yesterday Girl is unique among Kluge’s work, as it deals with this parapraxis with heavy-handed irony and features a Jewish protagonist. This is not the case in his later films.

Anita is stuck in yesterday. Beaten down, again and again, Anita takes her losses with stride in an almost flippant and provisional manner; a one-night stand with a strange man means a night off the streets; a forged address on sales slips means a day’s wages; a short stay in prison means free healthcare. One scene juxtaposes still shots of Anita sleeping with a sped-up time-lapse of a cafeteria. They move so fast through time, they appear as blurs. Anita is not just figuratively stuck in the past, she is the past. Meanwhile, everyone else around her is desperately trying to keep the past from catching up to them; they fear that “yesterday will come tomorrow.”

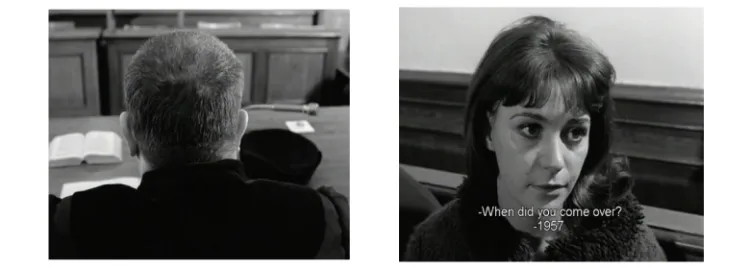

Anita’s existence reminds “ordinary” Germans of their guilt, so they treat her as if she were invisible, passing her on to be someone else’s problem. The narrative is markedly pessimistic, with the only reprieve being Anita’s unwavering spirit and unpredictability. At the beginning of the film, Anita is sitting in a near-empty courtroom, attending her court hearing; she has been accused of stealing a cardigan. For such a trivial offense, the judge (Hans Korte) treats her with such severity one would think she was being accused of murder, not petty theft. The scene’s opening shot is of the back of the judge’s domineering head. While Anita is shot from a high angle, the judge is shot from a low angle, making the power imbalance clear. Here, Yesterday Girl depicts Germany’s zero hour after the Second World War, during which Germany repressed the traumas of the past, including questions of complicity, guilt for Nazi war crimes, and the inability to mourn their dead. The judge, who operates within the same system that had once delivered Jewish people to their deaths under the Nazi regime, is one of the many Germans guilty of complicity. He becomes the picture of German arrogance, sitting on his pedestal looking down at Anita, when it is really him who should be taken to task. Thus, to admit Germany’s crimes is to admit his own, something he is obdurately unwilling to do. The judge dismisses Anita’s claim that her grandparents’ deaths in the Holocaust had anything to do with her present condition, saying “Are you saying something you couldn't have been aware of until 1943-44 has anything to do with your present situation? Then let’s leave it. It’s in the past.” Instead, the judge interrogates Anita about her own past and is baffled to hear that she fled to the West. Here, the shot/reverse shot is interrupted. Just as the judge has taken control of the conversation, he has done the same with the camera. Anita’s voice has become softer, overtaken by the booming voice of the judge. Anita explains that she fled because she “felt unsafe,” to which the judge scoffs and tells her “I don't believe that. In my experience, they don’t affect young people.” Later, he asks Anita twice if she felt guilty for taking the cardigan. The exchange is so ironic, it is almost comedic; the ex-Nazi judge asking the Jewish woman whether she felt guilty. Anita’s answer: “It just came over me.”

Yesterday Girl is not a feminist film, nor does it pretend to be. The absence of feminism in New German Cinema continued well into the 1970s. No women signed The Oberhausen Manifesto and men dominated the New German Cinema movement. In 1979, German women filmmakers drafted their own manifesto, “The Manifesto of Women Film Workers.” This manifesto called for political, social, and creative recognition. Kluge’s portrayal of Anita is problematic because it infantilizes her, demeans her, and fetishizes her. While Anita’s fetishization may serve as a political statement, it fails to challenge the parameters of fetishistic discourse on Jewish women.

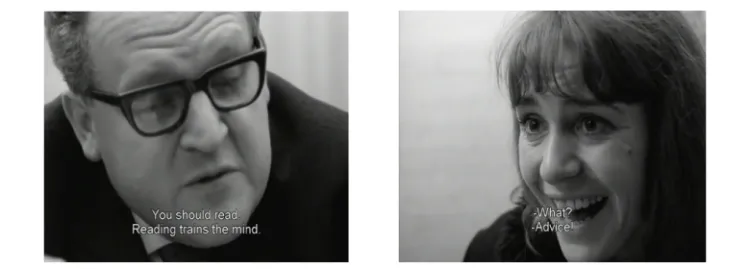

Anita’s life is circumscribed by men. They patronize her, claim they want to educate her and get her a job, have sex with her, but they never see or hear her. She is even spoken over by an unidentified male narrator. Upon seeking advice from a professor, he tells her “I want to do good for you. I want to educate you.” Like the courtroom scene, the professor is shot in a low-angle close-up, his body looking ever imposing in the center of the shot. Meanwhile, Anita appears smaller in the far right half of the shot. The shot compositions convey the professor’s power and Anita’s desperation. Anita begins telling him about a friend who is wanted by the police, but he interrupts and soliloquies about the intellectual benefits of reading. “You’re a good listener,” he tells Anita with a condescending smirk. He answers Anita’s pleas for help by philosophizing: “Well, that depends. Sometimes no advice is better than bad advice.” Similarly, an intertitle reads “If Pichota can’t help her, he at least wants to educate her.” He reads Anita Kafka’s The Trial— a fitting book given its Jewish protagonist is powerless in the face of severe bureaucracy— and he is short-tempered when she fails to understand it. Like the judge, we see the arrogant German epitomized in all men in her life, except, this time their arrogance manifests itself in the form of paternalism.

Yesterday Girl infantilizes and fetishizes Anita. The opening scene of the film shows Anita, amused and talking to herself while reading and eating. Later, she walks into a hotel lobby and switches her seat twice around the table, unperturbed by the judgemental stares she receives from the guests around her. Anita’s probation officer speaks to her as if she were speaking to a child, asking her “What is good?” To which Anita responds, “Whatever feels good.” Here, we learn Anita’s childish impulses primarily govern her choices. Anita continues to make choices based on her impulses throughout the film when she has an affair with her boss, when she buys a fur coat on her boss’s credit, and when she lies to Pichota (Günter Mack) about renting an apartment. An explanation of her infantile state may be that Anita is in a state of regression born out of trauma, a sort of arrested development. With no insight into her subjectivity, spectators are compelled to view Anita as a specimen; to watch as her life falls apart before our eyes. Her narrator contributes to the film’s ethnographic tone. In this way, we are Anita’s constant surveyors, studying and pathologizing her just like those around her. Spectators are not put into her shoes, for any attempt to identify with Anita would only lead to misunderstanding and a false sense of security. Rather, we are put into the shoes of the Germans who eye her with caution, waiting for her to either explode or, if we are fortunate enough, to absolve us of our sins against her.

In his essay 1962 “What Do the "Oberhauseners" Want?”, Kluge writes that “film should embrace social documentation, political questions, educational concerns, and filmic innovations” (Kluge, 203). Yesterday Girl combines aspects from the French New Wave and Italian neorealism, the product being a social realist, almost ethnographic study of postwar German society. Kluge is not afraid to underscore the irony of Germany’s parapraxis. Yesterday Girl’s final intertitle reads: “We are to blame for everything but if everyone knew, we would have Paradise on Earth.” That is to say, if Germany could face its demons, society would be better off. Anita is made a victim of Germany again, but this time it is more pernicious. They victimize her through paternalistic drivel and uncomfortable stares. In the end, Anita’s stasis of mind reaches its limits. She breaks down in tears and must be restrained by a nurse. Similarly, the collective delayed trauma caught up with Germany in the 1970s, resulting in explosions of domestic terrorism carried out mostly by students. Therefore, Yesterday Girl was ahead of its time in pointing out the irony of Germany’s collective repression of the Holocaust but fails to be progressive on gender.

Citations

Elsaesser, Thomas. “New German Cinema and History: The Case of Alexander Kluge” German Cinema Book, edited by Tim Bergfelder, Eric Carter, Deniz Göktürk, and Claudia Sandberg. British Film Institute, 2020, 407-417.

Kluge, Alexander. “What Do the "Oberhauseners" Want?” German Essays on Film, edited by Alison Guenther-Pal and Richard McCormick. Bloomsbury Academic & Professional, 2004, 203-205.

Rentschler, Eric. “The Oberhausen Manifesto.” German Essays on Film, edited by Alison Guenther-Pal and Richard McCormick. Bloomsbury Academic & Professional, 2004, 201-202.

Rentschler, Eric. “The Manifesto of Women Film Workers.” German Essays on Film, edited by Alison Guenther-Pal and Richard McCormick. Bloomsbury Academic & Professional, 2004, 235-237.

Schlüpmann, Heide. “‘What Is Different Is Good’: Women and Femininity in the Films of Alexander Kluge.” Alexander Kluge: Raw Materials for the Imagination, edited by Tara Forrest, by Jamie Owen Daniel, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2012, pp. 72–92. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt46n2tx.7. Accessed 25 Jan. 2021.