Kamen Rider Black Sun: Tokusatsu’s Past, Present, and Future

Essay by Ben Rotko '25 for Television Studies Course

Introduction

Kamen Rider Black Sun (Amazon Prime Video 2022) was the second reboot series produced in the long-running Japanese tokusatsu franchise, Kamen Rider. Tokusatsu is a Japanese word that literally translates to “special filming.” Coined by Tsuburaya Eiji, the special effects mastermind behind Gojira and Ultraman, tokusatsu is both a genre and a mode of production that utilizes extensive special effects to produce live-action science-fiction media.1 It is usually characterized by transforming heroes, giant monsters, and giant robots. Unlike the mainline installments of the half-century-old franchise, which usually have a unique cast and premise and produce around 50 episodes a year, Black Sun is a reimagining of Kamen Rider Black (TBS 1987-1988), one of the franchise’s most popular and beloved installments. The show has higher production values compared to mainline entries, is less concerned with toy promotion, and features ten episodes with longer runtimes. To paraphrase Sophia Staite (2021), “it is impossible to summarize the plot of [a Kamen Rider season] both briefly and accurately” (4). That said, Wikipedia’s plot summary does a serviceable job of explaining the premise, better than the Prime Video description, so we will use that:

"In the year 2022, Japan has entered a socio-political crisis since the government declared a coexistence between humans and the Kaijins, altered humans that came to be half a century ago via a classified government experiment. Izumi Aoi (Hirasawa Kokoro), a young human rights activist seeking to end Kaijin discrimination, meets two men named Minami Kotaro (Nishijima Hidetoshi) and Akizuki Nobuhiko (Nakamura Tomoya), former members of the Gorgom movement that revere the dying Creation King. The clashing ideals between Kotaro and Nobuhiko will shatter their society’s status quo and determine the fate of all Kaijins."

Unlike the mainstream Kamen Rider seasons, Black Sun is explicitly geared at an adult audience, rather than the franchise’s usual target demographic of children and adolescents. Black Sun takes advantage of this to deepen its story and visual language. Through its visual hyperviolence and use of parallels to current and historical events, Kamen Rider Black Sun both enhances and interrogates the tokusatsu genre.

Part 1: Hyperviolence

Kamen Rider Black Sun is a hyperviolent show. “Hyperviolent” in this instance refers to a level of on-screen gore that is above and beyond the norm of violent media. “Gore” consists of blood and guts resulting from on-screen violence and mutilation, accompanied by equally grotesque sound design. Additionally, a key component of hyperviolent media is a commitment to anatomical accuracy. Bones break, organs bleed, and intestines rupture as we expect them to on an anatomically accurate being (typically human or humanoid). In doing so, hyperviolence rejects the superhuman durability seen in action and genre media. Consequently, hyperviolent media uses its excessive gore as a core stylistic and generic marker. As a stylistic mode, hyperviolence can be used for multiple effects. The Mortal Kombat series deploys hyperviolence as shock value in the form of its famous Fatalities, while The Boys uses hyperviolence to display the absurd power of its superhero characters and enhance its satire. Kamen Rider Black Sun uses hyperviolence for a different purpose: to accentuate the posthumanism of the tokusatsu genre. The Kamen Rider franchise is, as a whole, posthumanist. As Se Young Kim (2016) puts it, “A central theme throughout Kamen Rider and tokusatsu history is the tenuous boundary that separates Self and Other” (54). The first Kamen Rider was a human cyborg created by an evil organization that rebelled against his creators, and future installments in the series continue this trend. Black Sun is no different. The titular protagonist, Minami Kotaro, is a kaijin, a genetically-modified human able to transform into an animal-like form, moving “back and forth between humanity and an alternative, indeterminate hybrid identity” (Kim 55). The series’ primary antagonists and enemies are also kaijin. A key tenet of Kamen Rider is that “the enemy in front of you and you are actually the same” (Staite 2021, 3). This theme traces its origins to the yakeato generation of writers who forged the original Kamen Rider stories, who were deeply concerned with “violence and the meaning of justice” (Staite 2021, 2).2 Black Sun uses hyperviolence to strengthen this connection and literalize it to the audience.

Throughout Black Sun, kaijin are beaten, bloodied, mauled, stabbed, decapitated, and more. In “Episode 2,” Akizuki Nobuhiko, aka Kamen Rider Shadowmoon, kills the Anemone Kaijin (Kakei Miwako) in a particularly brutal manner. After charging her, Nobuhiko bites into her torso while gripping her upper body with one hand and her lower body with the other hand. Using the force of his bite as a fulcrum, he proceeds to rip her in half with such speed that her legs remain standing for a moment. Depending on one’s sensibilities, this may be epic, grotesque, or possibly both, but it gives the Anemone Kaijin a definable anatomy that reinforces her status as a living, breathing being. When kaijin bleed, their humanity is reinforced. In most tokusatsu, enemies explode when defeated, often leaving behind nothing in their wake. These rubber-suited monsters may be fully-realized, three-dimensional beings with hopes, dreams, flaws, and sins, per Staite’s assessment of the tokusatsu genre, but there is a limit to how “human” a suited character can be without clear flesh and bone. Occasionally, human characters who die will have visible wounds, but not only does this happen merely once or twice a season, but these human characters often disappear into light instead of leaving behind a corpse. Additionally, the tokusatsu genre makes extensive use of wide shots during fight scenes. In some action shows drawing from the wuxia tradition, such as Xena: Warrior Princess, fight scenes are chopped up in editing, often showing one move (like a kick or flip) over as many as five separate shots. Tokusatsu fights, especially in Black Sun, give the audience a full view of the characters’ bodies, allowing their physicality to be fully realized on-screen.

In Black Sun, character deaths, whether human or kaijin, are given physiological realism. Consider one of the show’s most brutal and visceral scenes, where, in “Episode 7,” Kotaro tries to kill the Creation King. The “god” of kaijin and the source of a material called Heat Heaven that can heal kaijin wounds, the Creation King is portrayed via a giant animatronic puppet. The Creation King stands out as a production object because, unlike most tokusatsu monsters, it moves, breathes, and groans in ways that are frankly unsettling. With most tokusatsu monsters, “the audience understands that it is observing human actors,” even though disbelief is suspended for the purpose of narrative fulfillment (Kim 2016, 54). However, the size and complexity of the puppet beguile this understanding and makes it all the more shocking when Kotaro brutally mauls the Creation King and rips its heart from its chest cavity. Remember, within Black Sun, kaijin are human, just modified humans. It is only through showing the anatomical humanity of the kaijin that the show can truly interrogate the questions of prejudice and nationalism that it wants to.3 Shows like the aforementioned, mostly bloodless Xena cannot convey humanity through injury the same way a hyperviolent show like Black Sun can. Afterward, the Creation King’s heart lays on the ground, still beating in time with the score’s kick drum, further conveying that the Creation King was a living, breathing, human being. The physicality of the puppet is further reinforced in “Final Episode,” when Nobuhiko sits on the Creation King’s “throne,” and the body of the puppet is seen haphazardly lying dead on the side. During the final fight, Nobuhiko uses his newfound psychic powers to toss Kotaro into the Creation King’s body. The booming “thud” that results from the impact reinforces the puppet’s physicality. Rather than being a CGI creature, or a prop built into the set or scenery, the Creation King is an independent being. Despite advances in CGI, audiences can usually tell when giant monsters are computer-generated, and the Creation King is palpably tactile.4

Later in that same episode, Kotaro attempts to finish off the Creation King but is instead forcibly assimilated by it and becomes the new Creation King. Now, having established its characters’ physicality, Black Sun subverts it by having Kotaro’s Creation King form be stiff and unmoving. Where the first Creation King breathed deeply, this new Creation King is almost robotic in its stillness. If it weren’t for very faint breathing, one would almost think it was a statue. When the new Creation King is killed, it turns to stone and collapses into dust and sand. Black Sun subverts itself, just once, which makes the moment more jarring and unsettling.

Throughout the series, various characters repeat the refrain “The value of kaijin and human lives outweighs that of the earth. There is no difference in how much it is worth, not even 1 gram.” When it is revealed that kaijin are humans, this statement is made deeply literal. But by showing kaijin as living, breathing, bleeding beings, the refrain is made even more literal. By firmly establishing the anatomical “alive-ness” of kaijin, Black Sun reinforces its own themes and the wider themes of the genre.

Part 2: Black Sun in Context

Kamen Rider Black Sun is a remarkably radical text. It talks about the taboo subject of Japanese war crimes during World War II, comments on the co-optation of radical movements by established power structures, and criticizes right-wing nationalism. At once radical, this is also metatextual. Se Young Kim (2016) outlines how the tokusatsu genre arose from anxieties in post-war Japan; “Wrestling with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, tokusatsu imagines a reinvigorated nation through images of super robots and cyborg heroes” (48). In that paper, Kim argues that Kamen Rider Fourze (Toei, TV Asahi, 2011-2012) “reveal[s] how the ressentiment of tokusatsu is decidedly humanist. In other words, because tokusatsu performs the fantastical rearmament of Japan, the mode also perpetuates the hegemony of humanism, which shares an uncomfortable proximity to the very source of trauma itself” (59).5 Kim says that Fourze repudiates the “dynamic of exclusion” inherent to humanism, as outlined by Akira Mizuta Lippit (Kim 2016, 59; Lippit 2000, 10). He also argues that Fourze rejects the memory of trauma played out in tokusatsu. Kamen Rider Black Sun, I argue, takes this a step further and confronts historical trauma and injustices head-on.

Black Sun takes the historical and ideological foundations of tokusatsu and makes them a part of its story. Anne Allison contends that in post-war Japan, tokusatsu “provided a vehicle for reliving the terrors of the war relieved of any guilt or responsibility” (Allison 2006, 45). Repressed “neonationalist warriorship” surfaced in tokusatsu narratives as the desire to acquire a “final weapon” (Allison 2006, 99-100; Kim 2016, 50-51). This final weapon was personified in figures like the Shōwa-era Kamen Riders (including Kamen Rider Black). Black Sun reflexively weaves this into its narrative. Kaijin originated as military experiments during the war, intended to be an undauntable, unstoppable citizen-soldier. The two kaijin that would become Kamen Riders, Kotaro and Nobuhiko, were created to be the strongest among the kaijin, literally the “final weapon” that Kim describes. In fact, Black Sun implies that the more armored Kamen Rider forms (in contrast to the locust kaijin forms they initially assume) are the true realization of the kaijin experiments’ intent: weapons of war. Kotaro and Nobuhiko are just the only two strong enough to assume those forms. To clarify, this is not a neo-imperial text; these experiments are depicted as unambiguously cruel, disgusting, abusive, inhumane, and horrifying. In fact, the kaijin experiments serve as an analog to the real-life Unit 731, a unit of the Japanese military during the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II which conducted lethal human experimentation estimated to have killed up to 300,000 people. After the war, American occupying forces helped cover up these crimes. Some small acknowledgments have been made of Unit 731 by the Japanese government, like when attempts to remove mentions of the unit from Japanese textbooks were struck down by the Supreme Court of Japan in 1997. However, it still remains a taboo topic, and no meaningful attempts at restitution have been made. Rather than reenacting trauma “solely from the perspective of the victim,” Black Sun turns the camera back on the Japanese government and engages with the reality that Japan was also an aggressor in the war, and also committed many heinous acts.

For a reboot of one of the most popular installments of one of the most iconic tokusatsu franchises to engage with this kind of subject matter head-on is already radical. For it to then explicitly disavow the current Japanese political establishment and depict its protagonists assassinating a clear analog for former prime minister Abe Shinzo is genuinely insane. First, on a visual level, Prime Minister Donami Shinichi (Lou Oshiba) just looks like Abe. On the left is actor Lou Oshiba, on the right is Abe, and below them is Donami as he appears in Black Sun and another photo of Abe. Pay particular attention to the way Oshida’s hair is styled for his role as Donami and how it strongly resembles Abe’s gelled middle part.

Additionally, just as Abe had concerning ties to the Unification Church, Donami also has ties to a religious group, the Gorgom Party. Both were assassinated because of their connections to that religious group, and the series aired a mere 16 weeks after the real-life Abe Shinzo was assassinated (McCurry 2023).6 Both Abe and Donami’s grandfathers were also Prime Ministers: just as Donami Michinosuke oversaw the kaijin experiments before becoming prime minister, Kishi Nobusuke, Abe’s grandfather, was the architect of Japan’s rule of Manchuria during the 1930s, the very region where many of the Unit 731 experiments occurred. When the kaijin experiments, which began in 1936, are revealed to the world in “Final Episode,” a signature with the title “Chief General Affairs Officer” is seen on one of the documents. “Chief General Affairs Officer” is also the title Kishi Nobusuke was given in 1936. The parallels to real-life continue. The Gorgom Party emerged as a kaijin rights group in the 1970s, at the same time as widespread student protests in Japan (Oguma 2018). The murderous anti-kaijin hate group in Black Sun resembles, in costuming and tactics, the far-right Zaitokukai, a hate group that targets Zainichi.7 The kaijin neighborhoods in Black Sun visually resemble Zainichi neighborhoods, and in “Final Episode,” the text drops the facade of analogy and openly shows virulent anti-immigrant demonstrations among a montage of right-wing nationalist backlash.

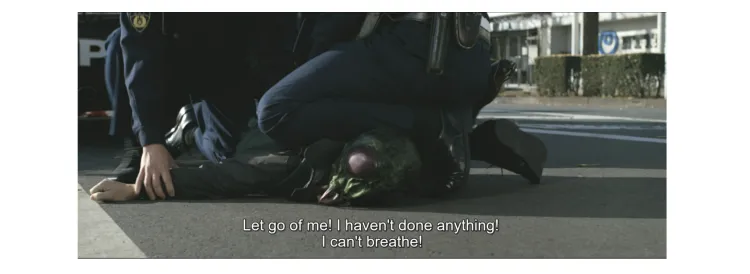

However, while Kamen Rider Black Sun openly rejects the neo-nationalist origins of the tokusatsu genre unique to the Japanese context, it also engages with wider global political trends. Beyond the text, these elements help the series bridge the gap with international audiences, as Kamen Rider Black Sun was released worldwide on commercial streaming platforms, something that does not usually happen for Kamen Rider media. “Episode 3” depicts clashes between kaijin rights demonstrators and anti-kaijin demonstrators. Flirting with the expository mode, Black Sun photographs these clashes in a manner resembling U.S. news coverage of protests. (In particular, the videographic footprint of the 2017 Charlottesville Unite the Right rally comes to mind.) Furthermore, Black Sun is unique in featuring two Black main characters: Oliver Johnson and his son Nick. Oliver Johnson joins the Gorgom activists in the 1970s, explicitly saying that he sympathizes with the kaijin’s struggle because of his own experiences with racism.8 Japanese nationalists perpetuate a narrative of Japanese ethnic homogeneity which, while not removed from reality, is exaggerated to promote a nationalist narrative at the expense of immigrants and indigenous groups like the Ainu (Jozuka 2019; Oguma 2020). By including Black characters, the show helps puncture this narrative. Oliver later becomes the minister of a Baptist church, evoking the many Baptist leaders of the Black freedom and civil rights movements in the United States, (including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.). In “Final Episode,” Black Sun depicts a kaijin being detained by the police in a manner reminiscent of a globally-famous police murder.

I believe the image speaks for itself.

Ultimately, Kamen Rider Black Sun is a radical anti-nationalist political manifesto ensconced in a tokusatsu show. It literalizes the contextual origins of the tokusatsu mode, and in doing so, exposes dark chapters in Japan’s past and present. After Donami’s assassination, his right-hand man becomes Prime Minister. Shrewder and less concerned with his personal goals than Donami, this new Prime Minister ignites a wave of far-right sentiment and open bigotry across the nation and openly calls for Japanese rearmament.9 Donami’s kaijin-trafficking schemes are discontinued, but the Gorgom Party is reorganized under the new prime minister. Once a radical movement, Gorgom has now become an arm of the establishment, fostering antagonism towards immigrants and foreigners to maintain control of the populace and distract people from the revelations about kaijin. Black Sun says that nationalism needs to be eradicated at the source and that removing one especially corrupt, despicable politician will not erase bigotry. This is a radical confrontation of tokusatsu’s origins.

Conclusion

Kamen Rider Black Sun was released as part of the Kamen Rider 50th Anniversary Project. In a year supposedly celebrating the history of Kamen Rider, Black Sun instead chooses to address the darker parts of that history. This is a subversive and radical act of television production. At the same time, the show uses a hyperviolent sensibility to give physicality and anatomy to its rubber-suited characters. They bleed, break, and cry out in pain, giving a visceral reality to the Kamen Rider series’ fundamental proposition that “the enemy in front of you and you are actually the same” (Staite 2021, 3). Kamen Rider Black Sun is at once a subversion and critique of the tokusatsu genre while also being an affirmation of what Kamen Rider stands for. Se Young Kim brilliantly explains how Kamen Rider Fourze “represents a radical break in the postwar ressentiment in the Japanese tokusatsu tradition” and that it “does not merely reject the history of atomic trauma in Japanese science fiction,” but “fully engages it.” However, he also says that Kamen Rider installments “have not followed in Fourze’s precedent” (Kim 2016, 64-65). This is unprovable, but Kamen Rider Black Sun reads as a response to Kim’s argument. It takes engaging with the history of trauma in tokusatsu to another level, ingraining the ressentiment of tokusatsu into the narrative’s diegetic backstory and using that as a springboard to critique the politics of that ressentiment in both a domestic and global context. It does this while still providing healthy doses of bloody, brutal action that elevate the franchise’s core themes. Kamen Rider Black Sun provides a blueprint for a radical reinvention of tokusatsu that looks to the future while reckoning with the genre’s past.

1 Japanese names written in the “conventional manner, with family names written first,” per Kim (2016).

2 The yakeato generation were children during World War II and “grew up amidst the burned-out ruins” (Staite 2021, 2).

3 Some Kamen Rider fans were turned off by the show’s gore, but the show has the highest age rating possible in all regions, so this gore is not unexpected and was also advertised in the show’s promotion. As a reboot intended for adult audiences, Black Sun is able to engage with these core tokusatsu themes on a visceral level.

4 That said, Black Sun does use CGI to convey physicality through hyperviolence, such as when the molded mouthpiece on Kotaro’s Kamen Rider helmet opens up to reveal a set of human-like teeth that he uses to bite the Creation King.

5 “Ressentiment” is a term commonly used by Nietzsche that refers to a “deep-seated resentment, frustration, and hostility accompanied by a sense of being powerless to express these feelings directly” (Merriam-Webster).

6 All 10 episodes of Kamen Rider Black Sun released at the same time on October 28th, 2022. Abe Shinzo was assassinated on July 8th, 2022. The production team surely had time to remove Donami’s assassination, but they chose not to.

7 Zainichi refers to people of Korean descent in Japan.

8 Oliver is, to the best of my knowledge, played by a Senegalese-Japanese actor, so whether he refers to racism experienced in Japan or somewhere else (such as the United States, as Oliver speaks English) is unclear. Either way, Black Sun is engaging with subject matter that tokusatsu has never dealt with before.

9 The new Prime Minister also happens to bear a resemblance to the current Japanese PM, Kishida Fumio, a disciple of Abe Shinzo. In 2022, Kishida increased Japan’s military spending by twenty percent (Reynolds 2022).

Works Cited

Abel, Jonathan E. “Masked Justice: Allegories of the Superhero in Cold War Japan.” Japan Forum, vol. 26, no. 2, 2014, pp. 187–208., https://doi.org/10.1080/09555803.2014.900512.

Allison, Anne. Millennial Monsters: Japanese Toys and the Global Imagination. University of California Press, 2006.

“Kamen Rider Black Sun.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 4 Nov. 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kamen_Rider_Black_Sun#Plot.

Kim, Se Young. “Human/Cyborg/Alien/Friend: Postwar Ressentiment in Japanese Science Fiction and Posthuman Ethics in Kamen Rider Fourze,” Cinema: Journal of Philosophy and the Moving Image 7 (2016): 48-66.

Lippit, Akira Mizuta. Electric Animal: Toward a Rhetoric of Wildlife. University of Minnesota Press, 2000.

McCurry, Justin. “How Shinzo Abe's Murder and His Ties to Moonies Blindsided Japanese Politics.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 10 Jan. 2023,

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jan/10/how-shinzo-abe-ties-to-mo….

Oguma, Eiji. “What Was and Is ‘1968’?: Japanese Experience in Global Perspective.” The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus, vol. 16, no. 11, ser. 6, 1 June 2018. 6,

https://apjjf.org/-Oguma-Eiji/5155/article.pdf. Accessed 29 Mar. 2023.

Oguma, Eiji. 「麻生発言」で考えた... なぜ「日本は単一民族の国」と思いたがるのか?. 5 Feb. 2020, http://mmdesign-jpn.la.coocan.jp/shoko/oguma15.htm.

“Ressentiment.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ressentiment. Accessed 28 Mar. 2023.

Reynolds, Isabel. “Japan Budget: Defense Spending Increased by 26% for 2023.” Bloomberg.com, Bloomberg, 23 Dec. 2022,

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-12-23/japan-begins-defense….

Staite, Sophia. “Kamen Rider: A Monstrous Hero.” M/C Journal, vol. 24, no. 5, 2021, https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.2834.

Steimer, Lauren. “From Wuxia to Xena: Translation and the Body Spectacle of Zoë Bell.” Discourse, vol. 31, no. 3, 2009, pp. 359–390., http://www.jstor.org/stable/41389824. Accessed 18 Mar. 2023.

Media Cited

The Boys. Kripke Enterprises, 2019- .

Gojira (Godzilla). Directed by Ishirō Honda, special effects by Eiji Tsuburaya, Toho, 1954.

Kamen Rider Black. Directed by Yoshiaki Kobayashi, Toei Company and Ishimori Productions, 1987-1988.

Kamen Rider Black Sun. Directed by Kazuya Shiraishi, Toei Company and Ishinomori Productions, 22 Oct. 2022. Amazon Prime Video, www.amazon.com/gp/video/detail/B0B8TDY67R.

Kamen Rider Fourze. Toei Company and Ishimori Productions, 2011.

Mortal Kombat. NetherRealm Studios, 1992.

Ultraman. Created by Eiji Tsuburaya and Tetsuo Kinjo, Tsuburaya Productions, 1966-1967

Xena: Warrior Princess. Directed by John Schulian and Robert Tapert, Renaissance