The Boy Who Swallowed a Star: Transformational Synthesis in Howl’s Moving Castle (2004)

Essay by Josephine Low '27 for Animation and Media Course

Metamorphosis is the heart of Hayao Miyazaki’s Howl’s Moving Castle (2004). It straddles geographic, cultural, and temporal boundaries as a cultural artifact: a film produced by a Japanese studio, adapted from British author Diana Wynne Jones’ 1986 novel of the same title, now reaching an international audience in subbed and dubbed translation. Howl’s Moving Castle often diverges from the original plot in favor of phantasmagoric, spectacle-driven imagery with magical realism enacting the characters’ internal psychology. Both the character’s bodies and the landscape surrounding them take on metaphorical resonance during these “dream sequences.” The form of Studio Ghibli animation mirrors its function, blurring the boundaries between physical bodies and abstracted landscapes. The flashback sequence in which Sophie enters Howl’s childhood memory of his pact with the fire demon Calcifer can be taken as a microcosm of Howl’s Moving Castle’s take on this aspect of Ghibli style as a whole. Howl gains the abstract power of the supernatural landscape by symbolically swallowing a star, in exchange for losing a piece of his humanity by sacrificing his heart; Calcifer loses his abstract power by allowing himself to be consumed, in exchange for gaining tangible physicality by possessing Howl’s heart. Sophie acts as an audience surrogate, bearing witness to the human-supernatural interaction enabled by the fluidity of animation.

The interaction between Howl and Calcifer is a reciprocal exchange in which each take on aspects of the other, with their in-universe supernatural or human qualities reflected by the way they are depicted in animation style. As animation scholar Rayna Denison describes in the essay “Anime’s Bodies,” the unions and transformations depicted in anime “challenge our conceptualizations of what it means to be human...because these bodies defamiliarize our concepts not just of animation’s cultural purposes and potential, but of humanity itself.” Initially, Howl and Calcifer are diametrically opposed in vertical composition (Fig. 1). Young Howl is bound to the solid mountains and grassy meadows of the physical world; the entity we later learn is Calcifer in abstracted star form floats through an incorporeal expanse of sky. Howl’s hands are already outstretched, implying his desire to transcend his original state and interact with the magical unknown. The inherent identity of a falling star similarly implies the potential of motion as gravity pulls it inexorably to the earth.

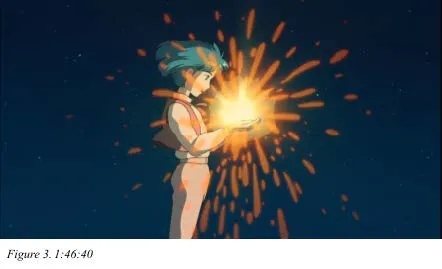

Although Howl is semi-realistically depicted as a human child, Calcifer’s star form is more indexical than iconic. The falling stars in Howl’s Moving Castle are not an accurate depiction of meteorites; rather, they evoke storybook illustrations, a child’s imagination, or the bright streaks or “starburst effect” seen when squinting at a light source too bright to focus upon. When Howl catches the star, the two contrasting modes of representation collide in the same mise-en-scène. An explosion of light obliterates clear boundaries of child and star, land and sky, realism and spectacle. In the next close-up frame, Howl holds the star in both hands, reestablishing the original separation between them (Fig. 3). Howl’s body imposes realistic laws of physics upon the abstract entity of the star by holding it aloft; the ever-shifting star illuminates him with unexplained light but does not burn. Howl visibly speaks, but it is unclear whether the star responds, still lacking a mouth or any identifiably expressive features. Howl then decides to eat the star (Fig. 4). This image is viscerally evocative; as the audience is immersed in the visual spectacle of abstract and realistic art and the auditory spectacle which will later be discussed, they are forced to reckon with a gesture of taste and touch. The depiction of Howl eating - bringing his hands to his face and swallowing — is physical and familiar, unlike the star he is eating. In the act of consumption, Howl’s physicality and the star’s abstraction are literally and metaphorically united on the picture-plane of the screen. As in their initial contact (Fig. 2), they become one body, both real and not-real. Howl’s mouth fuses with the center of the star, amorphous shapes of light extending outwards around him.

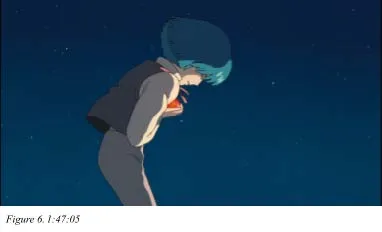

When he has fully swallowed it, the liminal state of transformation ends and Howl appears to return to his original human state. However, Howl’s physical body quickly revolts against his metaphysical union with the star. He clutches his chest and coughs as if experiencing heartburn (Fig. 5). The visceral shock of eating is emotionally extended by the depiction of a child in pain. Finally, Howl and the star re-separate into distinct entities, though both are changed (Fig. 6, Fig. 7).

After this supernatural encounter, arguably a kind of adolescence, Howl is no longer an innocent child. He has gained magic which gives him power over his world, which is animated elsewhere in the film in a style evocative of the star’s abstraction, and is closer to the character first introduced in the narrative as an adult. The star is now recognizable as Calcifer, who gains tangible form with defined boundaries, while still maintaining vestiges of his former abstraction in the volatile shape of fire. In addition to being partially bound by physics, Calcifer also gains semi-humanoid eyes. The temporary union and subsequent transformation of Howl and Calcifer not only recontextualizes the two character’s backstories, but the very rules of the diegetic world itself.

In this scene, Sophie becomes a vessel for the audience to project upon. Her presence as the protagonist enables the scene’s existence; the film continuously cuts between close-up shots of Howl and Calcifer and wide shots to emphasize their separation from the main storyline. In the constructed world of Howl’s memories, Sophie is physically separated from the action by a lake (Fig. 8). In the The Art of Howl's Moving Castle, an officially produced film companion, this body of water is described as “the black water of time,” which hints at its purpose as a metaphorical barrier. Sophie is separated from young Howl and Calcifer because she does not belong to their world; she is a visitor from the future. Her existence in the memory landscape is inherently unstable, which is demonstrated by the ground continuously shifting beneath her feet (Fig. 9). Once the pact between Howl and Calcifer is complete, the scene’s purpose in the narrative has been fulfilled, and Sophie collapses through the landscape of the world entirely. As she falls, the landscape and Howl and Calcifer’s bodies dissolve into an abstracted mass in a final act of metamorphosis, obliterating time in addition to matter (Fig. 7). She calls out to both characters by name, and they turn to acknowledge her in a subtle fourth-wall breaking reversal of roles: the observer becomes the observed. By bearing witness to this supernatural interaction, Sophie too is transformed: “I know how to help you now!” she calls out before being returned to the present.

The enduring cultural legacy of Howl’s Moving Castle lies in its ability to transcend boundaries. It follows established fantasy tropes, then unexpectedly subverts them. It plays with continuums as far ranging as morality, gender, culture, and production, using a combination of traditional hand-drawn animation and CGI technology. To borrow Denison’s language, the film’s bodies are continuously changing into truer versions of themselves. The relationship between animation and its implied audience may be compared to the mutually transformative relationships in Howl’s Moving Castle — the spectator transforms the film through their individual interpretation, and they are themselves changed by bearing witness to art.

Works Cited

Denison, Rayna. “Anime’s Bodies.” The Animation Studies Reader, edited by Nicola Dobson, Annabelle Honess Roe, Amy Ratelle, and Caroline Ruddell, Bloomsbury, 2019, 257-276.

Howl’s Moving Castle. Dir. Hayao Miyazaki. Toho, 2004. Max. Web. 3 October 2023.

Miyazaki, Hayao. The Art of Howl's Moving Castle. VIZ Media LLC, 2005.