Jude Sandy on directing "Selling Kabul"

An interview with Visiting Assistant Professor Sandy about directing a regional premiere at InterAct Theatre Company

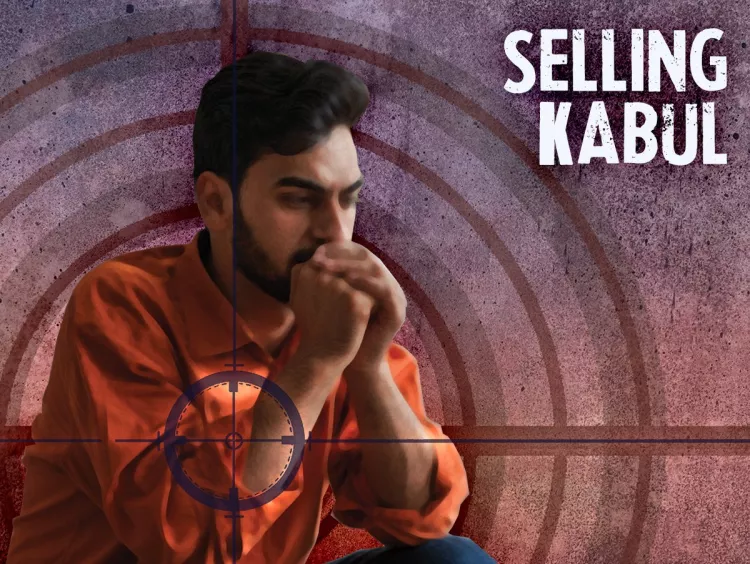

Publicity image from InterAct Theatre Company.

In “Selling Kabul”, Taroon, a former interpreter for the U.S. military, is hiding from the Taliban in his sister's apartment while he awaits the arrival of a promised American visa. But on the eve of his son's birth, he is determined to visit his wife and newborn child, putting his entire family in grave and immediate danger. Jude Sandy directs, and Swarthmore Costume Shop manager LeVonne Lindsay designs the costumes for this production.

SR: Hi Jude, thank you so much for sitting down with me to talk about “Selling Kabul”! First, I’d love it if you could tell me a little bit about the play.

JS: The play takes place on a fateful night in Kabul, Afghanistan during a period of American withdrawal and rising Taliban reprisals. An Afghan woman has been hiding her brother, who has worked as an interpreter for the American military, in her apartment for four months while he waits for a visa that was promised to move him and his family to the United States. And it's a critical night for them all, firstly because her brother’s wife has been forced to give birth without him, and secondly because the Taliban’s hunt for him has renewed with violent consequences, and they’re getting closer. She and her husband are doing everything they can to keep him safe, but things are spiraling dangerously out of their control. And what's incredible about the play - apart from it being a powerful drama about an Afghan family that speaks so vividly to everything that’s going on in the world right now - is that it so palpably demonstrates the human toll of big historical disruptions that many of us here at home tend to look upon theoretically.

It makes the cost of America’s withdrawal from Afghanistan profoundly relatable in terms of its great endangerment of the Afghan population and particularly the lives of thousands of people who actively embraced America’s presence and collaborated with our mission there. And at the very heart of the play is what people will do, both honorable and questionable, in order to save one another in the face of great menace and near impossible choices. All the characters work desperately to keep one another alive, keep their families together, and keep their loved ones safe. It's an incredible piece of theater. And it’s the last thing that I imagined that I would have the opportunity to direct!

SR: Oh, that’s interesting! Does this piece feel different for you than your usual artistic work?

JS: It is, and then it isn't, and I guess that's where the particular and the universal really get to play together. For me, as an artist, I'm always very interested in the politics of human relations, and the human relations within our larger politics. And so, in that regard, this play sits squarely within my set of concerns. There's something about the play that is very humble, and I think of myself as a humble theater maker; my interest is in getting to the bare essentials of the connections between human beings on stage. You know, I like spectacle as much as anyone else does. But primarily, I'm concerned with human beings being in relationship with one another and navigating how they find, or fail to find, belonging and community with one another. And then what the consequences of the navigation of that belonging are for people from different perspectives or needs, different value systems, identities and stations in life. So in that regard, this play makes perfect sense for me, right? It happens in the confines of one apartment over the course of a single night. We witness these characters in real time, grappling with real-life emergencies. And their relationship to the larger world and their very survival are so powerfully at stake for every single one of the characters.

One of the things we've been discovering, as we've been in rehearsal- and this was not immediately apparent to me on the page, but it has been a gift to discover- is that ultimately the play is about what love demands of us and what love makes possible. About the kinds of sacrifices people are willing to make for love, for family, for people who they feel belonging with. And of course, we're producing this play in this moment of such incredible tumult. I mean, there’ve recently been three devastating earthquakes in Afghanistan in a time of greatly reduced humanitarian aid to the country because of the Taliban takeover, not to mention what's happening in Israel and Palestine. It’s a sadly perfect moment to work on this play that addresses the fallout from large scale cataclysm, but which on the immediate scale is actually about people fighting for those they love. And how these extreme circumstances that are wrought by human violence can in some ways bring that love out even more powerfully. You know, as we remember the catastrophe of the American withdrawal from Afghanistan, or as we're watching the news now and hearing the testimony of people on both sides of the Israel/Palestine conflict who have lost family members, we feel with great immediacy how much love they hold for them, right? It becomes more apparent, more visceral. And that's so powerfully distilled in this play.

Sylvia Khoury, the playwright, was engaged in a work of prescience in writing this play in 2020 - the premiere was interrupted by the pandemic. To have written this play about the dangers of the Taliban’s empowerment over Afghan society and its people - and then for us to see what transpired in the intervening couple of years with the American withdrawal and the Taliban takeover- she was prophesying, she was warning us! So in that regard, I and almost anyone who has been watching the news can feel completely at home in the play. And at the same time, there's the sharp cultural specificity of the piece! (laughter) And in that sense, I've had to really rediscover humility as a director.

SR: Sure! Do you have people in the room to talk about the cultural specificity of Afghanistan?

JS: We do. We have a brilliant cultural consultant, Humaira Ghilzai, who has worked on this play as a consultant and dramaturg multiple times. Humaira brings a rich lived experience of Afghan culture, but also a deep understanding of this play and of theater, and what it means to try to reflect Afghan culture honestly in production. We've been fortunate to have that support, and InterAct Theatre Company’s artistic director, Seth Rozin, was adamant about securing that support for the project. We also have a cast of talented, sensitive and deeply informed actors. Awesta Zarif, who plays Afiya, was born in Kabul, and has played the role twice before. So she too brings a unique understanding of the needs of this particular work.

For me it's been a gift to venture into the world of this play - a world I didn’t previously know beyond what I read or watched in the news - because I've had to, as a director, be really clear about what I don't know or where I need someone else’s expertise. And it's been liberating as a collaborative artist to walk into a room and say, I don't know everything, to have to ask questions, rather than casting myself as someone coming in with answers. And to me, that's the most beautiful part of any collaboration, when we can all make discoveries and choices together. It's been joyful! It's how I try to work anyway, but in this case it's mandatory! Everyone in our production process must be seen as a full collaborator with full authority in the room. In that way, it feels like an ideal experience.

SR: When you have a show that has such emotionally intense material like this, what structures do you bring into the room to allow people to engage deeply, while staying emotionally safe?

JS: Yes! One of the things that I always insist upon, is that we do really devoted daily check-ins. And that includes everyone in the room: the actors, the stage manager and production assistant, the designers when they’re with us and any guests who come to watch us work while we’re in the rehearsal room. And there may be days when the check-in is five words or less, or merely a moment of breathing together. Because I have a background as an actor first, one of the things I've been clear about for myself, is that it's actually not necessarily realistic or healthy to think I can or should completely leave the rest of my life behind as I enter the work of telling a story. Nor is it as efficacious as we'd like to think it is, to pretend that we can banish the reality of our lives outside the room. It all comes in with us. And we're all better off if we have some small collective understanding of what is coming into the room with us from one day to the next, some acknowledgment of it all as valid in this space in which we each contribute so much heart and grit to make the work of theater happen. So we try to be diligent about check-ins. When I first started directing, there would be days when I forgot to do the check-in, and I would quickly see how the ensemble spirit we’d been working to build would fray, sometimes in barely perceptible but always consequential ways. And there are days when the check-in might take half an hour, even with a small cast; and it's easy to think, oh, this is taking too much time, you could have been staging something in this time. But that half hour determines the success or failure of the rest of our day.

Another thing we've been practicing in this particular production that I'm doing dedicatedly for the first time, is to do physical check-ins as well. To ask everyone to tell us, where am I comfortable being in physical contact today? It's another way that we get to map boundaries with one another, both physical and emotional, because the body is both, right? And that has been giving the actors actually a kind of freedom. Because we are all coming into each day with a renewed sense of information about one another, where we can exuberantly explore with one another and where our limits are.

And then at the end of the day, I try to remember to take a little moment together, because the material in this play is so fraught, and sometimes we end on material that feels heavy, and we need ways to relinquish some of it as we return to the world outside the rehearsal hall. We've been finding a practice organically of breathing together at the end of the day. With material like this, one of the things that I've been trying is to be a little more flexible with how we use time - to not police time as strictly as I might otherwise, because we need space to attend to some of the tender stuff that the play brings up. I try to come in with a very clear sense of our goals, and to communicate those goals so people can map for themselves how they will be moving through the day. And then I keep updating people regularly as things shift, because they always do, of course, and to include everyone in the decision making around how things shift. For example, I might ask people, what do they have the capacity to do today? You know, Is this too much? I want to foster trust with fellow artists. I want to encourage artists to work on their terms within the collective. And, and just to work gently first, easing towards the vigor and athleticism that’s integral to the work we do. And what I've been finding is that if we're working gently, which includes working gently with time, we actually have space to laugh. And that’s been critical. Because laughter is epiphany. And good theater is epiphany too. So we make space to laugh, and to tell stories. Sometimes we're on our break, and the 10 minutes are over, but one of us is telling a good story. You can’t interrupt that! Telling good stories is our work! So I'm like nope - we can take these next three minutes to finish hearing this great story. Because we need that deep knowing and trust and listening to one another, which is the belonging we’re building. To me, all of that belonging shows up on stage.

SR: Absolutely. It always does.

JS: It does! And I’m lucky to be working with a group of fiercely talented, conscientious and generous artists cultivating belonging together in the service of sharing this story with our community - like, they walk one another home at night! So, for me, it's all about being clear that I respect my colleagues, that I respect their needs as artists, and that I’m grateful for all they’re pouring into the work. That they aren't to be condescended to, as I think, has sometimes been a habit in our profession; to patronize or even coddle. That my work as a director is to communicate clear expectations and craft space for the fulfillment of collective ideation, and then trust that everyone will realize those expectations in the ways they are best able; and out of that we create something special. And for that I try as often as I can to thank my fellow artists. I find myself saying “thank you” more times in a single rehearsal than I probably do in a week or even a month outside of rehearsing. And that’s a great gift, the opportunity to say thank you! And for us to laugh- for us to laugh together.

SR: Beautiful. Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me, Jude. How can the Swarthmore community learn more about the show and get tickets?

JS: The show begins performances on Friday, Oct 27th, and tickets are on sale now at https://www.interacttheatre.org/selling-kabul!