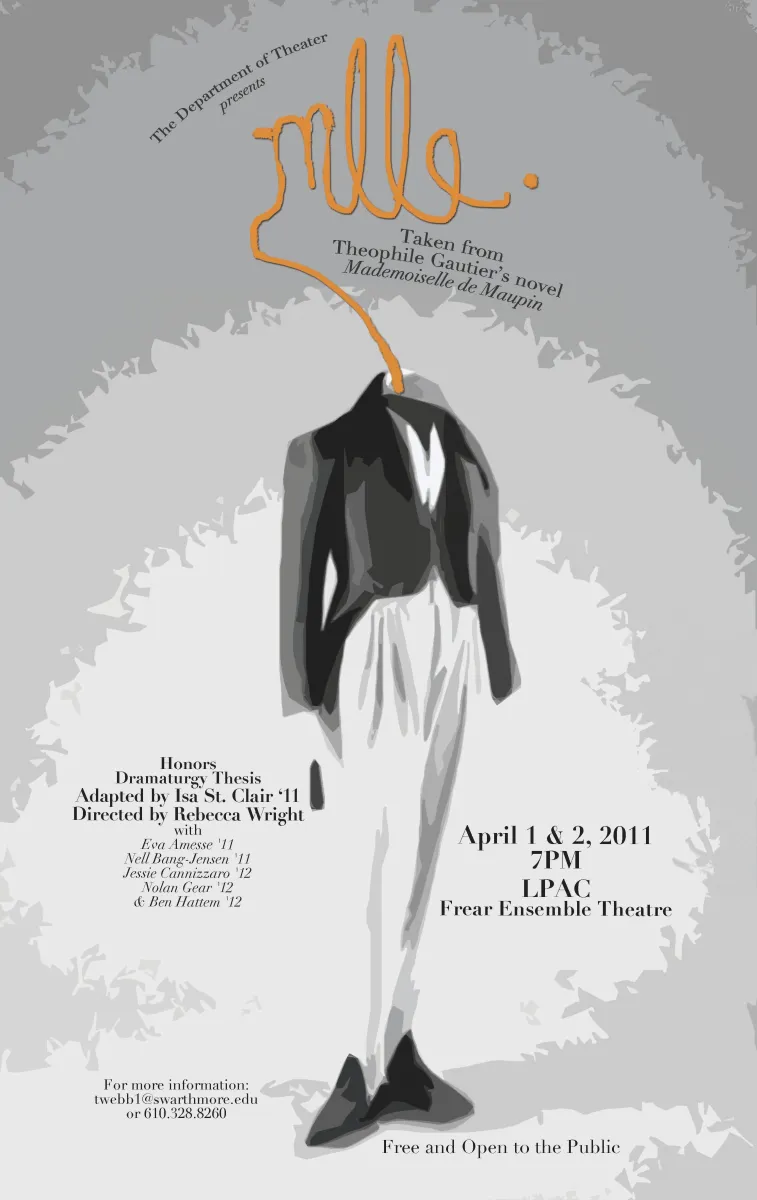

MLLE.

Honors Dramaturgy Thesis

HONORS DRAMATURGY THESIS (Isa St. Clair '11)

mlle., an adaptation of Theophile Gautier's 1834 novel Mademoiselle de Maupin, tells a story of disguise, desire, and a very tangled love triangle. The play explores gender, sexuality, Shakespeare, Romanticism, and the farce we all make of ourselves. Adapted by Isa St. Clair '11. Directed by Rebecca Wright, with Eva Amessé '11 (Ninon), Nell Bang-Jensen '11 (Rosette), Jessica Cannizzaro '12 (Theodore/Mademoiselle), Nolan Gear '12 (Nolan Gear) and Ben Hattem '12 (Silvio).

When Theophile Gautier published the novel Mademoiselle de Maupin in 1834, Paris flew into uproar. Polite society swiftly condemned the lascivious novel in public and eagerly devoured it in private. For though it was the height of the Romantic movement in France, no one had yet prodeced such an admixture of hedonism, romance, ars gratia artis, and a revolutionary treatment of gender and sexuality as Gautier did in Mademoiselle de Maupin. Throughout the novel, the multivalent characters discover and rediscover their own gender identities and sexual preferences/performances, displacing sexual norms and (self) constructed identities. As readers, we are never quite sure if we are seeing masks or faces, if we can access an essential truth regarding these characters and their desires, or if that truth exists at all.

The nimbus of controversy surrounding the novel persisted for decades; Mademoiselle de Maupin was the subject of an American lawsuit over its alleged obscenity as late as 1922. But its fame - or infamy - has waned in the intervening years. Indeed, the material that made the novel so shocking and forward-looking upon publication is no longer particularly progressive and actually somewhat problematic; Gautier was a revolutionary 1834, but is a little outmoded in 2011. If controversy stems from the piece today, it is because of the novel's outdated attitudes regarding "acceptable sexuality," its implicit reinforcement of the gender binary, and its inherent anxiety regarding issues and identities that have since gained a greater, though imperfect acceptance in today's world. In this play, I have tried to access these issues through the Romantic vocabulary (linguistically and ideologically) in which they were written; the result is a play in which the line between performance and reality, masks and faces, then and now, is hopefully even more tenuous than it was in 1834. ---Program Notes, Isa St. Clair '11 (April 2011)