C’est l’Afrique!

Alumni couple discovers a new sense of themselves (and lots of dust) during an extended stay in West Africa

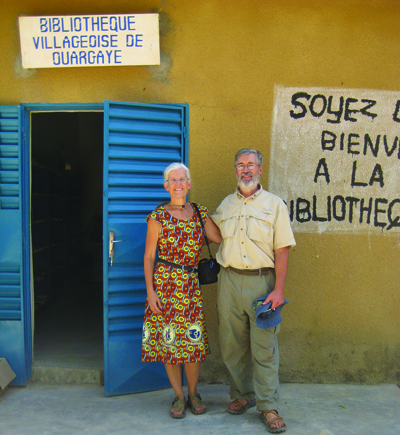

Emily Howe Wilson ’72 and husband Richard ’73 visited the public library they helped fund in the village of Ouargaye in Burkina Faso.

The first time we encountered Burkina Faso was in 2007—while visiting our son who was there with the Peace Corps. While there, we met Abga, an ecoguide with whom my wife Emily ’72 has since kept up via email (in French, Burkina Faso’s official language) and who adopted her as his mother. When we went back to visit Abga in 2009, as tourists instead of Peace Corps parents, we were again struck by the poverty—it’s among the 10 poorest countries in the world.

As Emily says, her “do-good” gene kicked in during the first visit. Social activism is something for which Swarthmore—with its Quaker heritage—is known. But it takes a while to really affect some of us—and get us off our duffs. She started looking for organizations to work with in 2007 and found the California-based Friends of African Village Libraries (FAVL). When we were finally able to make a sizable donation, FAVL used it to establish a new public library in the village of Ouargaye. (It’s FAVL’s 12th library in Burkina Faso; see FAVL.org.)

Last winter, with Emily finally retired from the Brown County Library in Green Bay, Wis., we had more free time. We decided to return to Burkina to visit Abga again, to see more wildlife and birds, and, frankly, to avoid winter in Wisconsin! I asked Emily to find us something to do there.

But c’est l’Afrique (this is Africa!). We wound up just spending three months mostly in Diapaga and W National Park, getting more familiar with Burkinabé culture and village life in Diapaga.

Our life in Diapaga was comfortable by Burkinabé standards. Abga had arranged a villa for us to use—three bedrooms, two baths, a kitchen, a caretaker, electricity, water, and so forth. But we still needed to adjust to the realities of a Fourth World nation. Everything in the house was covered in orange dust, as were we. Any passing vehicle, especially the always-overloaded trucks, would leave a cloud of dust, as the nearest pavement was 50 miles north. The electricity often went off, sometimes for only a few minutes, sometimes for hours. Water came from a chateau (water tower) out back that was filled via electric pump from a cistern below. If the municipal water system was functioning, a woman brought in six 55-gallon barrels, one at a time, on her donkey cart to fill the cistern. She transferred the water one bucket at a time.

The Wilsons observed the reroofing of huts with mats made from tall grass.

Of course we didn’t drink that water. We drank it bottled, available from the wholesaler, although it was often fini (sold out). When that happened, we’d try to find a store that still had some—a not-so-simple task. I think we bought out three different stores during our stay.

Shopping proved an interesting challenge. There are dozens of stores in the village, but it’s never clear just what they might be selling. An average-sized one (i.e., about 10 feet by 10 feet) might have Coke, canned tomato paste, soap, bagged macaroni, cigarette lighters, powdered milk, flip-flops, instant coffee, phone cards, Maggi (bouillon) cubes, and if we were lucky, water.

However, one doesn’t just go to a store and ask for water. That would be extremely rude! You have to greet the patron (proprietor) and ask “Ça va?” (“How’s it going?”)

The answer is always “Ça va.” (“Fine.”)

Then of course you inquire about the family. Always the answer is “Ça va.”—even if the proprietor’s wife just died.

After the pleasantries are completed, you can inquire about water. The answer is usually no; after all, only white foreigners drink the bottled water, and I could count my counterparts on one hand. But the patron would always have a suggestion of someplace else to try. We would head to the next store and repeat the process.

In Burkina Faso, life in the slow lane is sort of forced on you. Nothing happens midafternoon during the repos (think siesta). We didn’t feel like doing much then either, with temperatures of more than 100 degrees! Relationships are much more important than accomplishing anything—that’s why you have to greet everyone you know—and even some you don’t—with “Ça va?” And that’s why 9 a.m. means sometime between 10 and noon, or later.

With friend Abga (left) and his wife, Honorine, the Wilsons visited W National Park’s Point Triple, at the point on the Mékrou River where Burkina, Benin, and Niger meet. Point Triple is an archaeological site and one of the earliest metal-working sites in West Africa. A year ago, Abga’s association of ecoguides received permission to set it up as a tourist encampment.

Emily always said she doesn’t do nothing well—i.e., she has to keep busy. Well, that’s not how it works in Burkina, but she adapted quite well. We found it very nice to go to the maquis (café) across the street each afternoon for a cold drink—beer for her, Coca (Coke) for me. If we wanted a snack with the drinks, we’d bring it with us. Many maquis serve only drinks, but they’d provide a plate for us for our beignets. Of course, before ordering our drinks, we’d greet the patron with “Ça va?”

And anyone entering would greet us—and we him (yes, him; only men spend time in the maquis). I use the term “enter” loosely, since we didn’t really enter the place; the inside was a small room (about 6 feet by 6 feet) where the extra beverages were kept. The seating was out back under a hangar (straw shelter), slightly blocked from the dust of the road. But in Burkina you can drive anywhere there isn’t a building or tree, so people coming to the maquis would drive (or ride a motorcycle) right into the seating area, kicking up that ubiquitous orange dust.

You don’t spend time in a place like that without either adapting and adopting the lifestyle or going bonkers. We adapted and adopted.

We learned to go with the flow at the campement (bush camp) at Point Triple in W National Park, where our hut had water, but the electricity was turned on for only about three hours each evening, so this precluded cold beverages. Because of the wild animals, we were not allowed to walk far by ourselves (although in the heat we wouldn’t anyway). One afternoon we walked past some buffalo about 100 feet away without realizing it—until we encountered them just over a rise from us. Lions came out during the night; we never saw them, although they woke us with their roaring. And plans for “tomorrow” sometimes meant the day after … maybe. As we sat in the 100-plus-degree heat looking at birds and animals, we thought, “Folks in Green Bay wouldn’t believe this.” Sometimes I’m not sure we did either. But since our daughter is planning to teach in the adjoining country of Mali, we know we’ll be back in a year or two!

After our first visit to Burkina in 2007, we came back to Green Bay appalled by the poverty and determined to try to do something. This time we adapted and adopted and really began to grasp the importance of relationships. We were changed in a different way—acquiring a new understanding of ourselves—our limitations and our personalities. g

Richard ’73 and Emily Howe Wilson ’72, who met at Swarthmore in 1968, have lived in Emily’s native Wisconsin since 1974.

Email This Page

Email This Page

October 14th, 2013 2:20 pm

Hello, This is a great story about real people having a real impact in Burkina Faso. Please connect me to Richard and Emily. My organizations Trees for the Future does quite a bit of work in the region, and I'd love to see if we can support their work.

John Leary '00