Reducing Gun Violence is Author Kennedy’s Aim

David Kennedy spoke intently and eloquently to a large audience at Swarthmore in April. He elicited questions from police officers, Quaker activists, and students alike. Photo by Stuart Watson

David Kennedy ’80, H ’11, Don’t Shoot: One Man, A Street Fellowship, and the End of Violence in Inner-City America, Bloomsbury USA, 2011.

David Kennedy ’80 describes his extra-ordinary book as a work of “experimental nonfiction.” Some people refer to it as a memoir. I call it an “autobiography of public policy.” Kennedy, a well-known and highly respected academic criminologist, tells the story of both his scholarship and his practical efforts to end gun violence in American cities. It is an unusually forthright book, intensely personal, and compelling in its message and conviction.

Kennedy is the director of the Center for Crime Prevention at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City and co-chair of the National Network for Safe Communities. He has spent the bulk of his career at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, beginning as a writer and becoming increasingly involved in research and public policy. His earlier book, Deterrence and Crime Prevention: Reconsidering the Prospect of Sanction, was called “a landmark rethinking of public policy” and “a primer on 21st-century policing.” He has traveled the scholar’s route.

But Kennedy is also on a mission. He brings a moral indignation to gun violence and its heartbreaking consequences, felt inequitably by residents of the inner city and by young men of color. His intent is not just to study gun violence but also to find solutions to end it.

Kennedy and his research team engaged thoroughly in fieldwork in inner-city Boston, gathering perspectives on violence from police, community members, and those directly involved in perpetuating violence. Kennedy’s conclusion?

Different segments of the community whose lives most directly intersect with gun violence fundamentally, unnecessarily, and tragically misunderstand and mistrust each other. Police believe that inner-city residents are indifferent to gun violence in their neighborhoods, because they appear not to react negatively and do not cooperate with police in bringing criminals to justice. Residents believe that police are indifferent to violence in their neighborhoods, because police, and the governments that employ them, do not commit the resources to solve the problem. Perpetrators of gun violence—mainly male youth in gang and drug-market–related incidents—live in a street community that has its own norms of respect and retaliation. They think the police act out of racism and animosity, and believe that their own neighborhoods accept the situation. Each community is wrong about the other, failing to recognize their common ground: Nobody wants gun violence.

Kennedy advocates the simple but complicated solution of having police and communities stand together, simultaneously warning youth that, when violence occurs, a united community and police force will react with immediate consequences. The warning includes information about how youth might make difference choices. For this kind of cross-community effort, police must admit their limitations and acknowledge that inner-city residents have good reason to perceive racism; residents must set aside their grievances and become engaged; youth must understand consequences and be offered support to resist pressures of the street. The focus is singular: to eliminate deaths from gun violence. As for other problems surrounding gun violence—especially the drug market and the dynamics of economic inequality—Kennedy says, yes, but we can actually solve this one problem without simultaneously having to solve the others. His intent is to stop the killing.

In 1996, Kennedy’s model became the centerpiece of Boston’s “Operation Ceasefire,” which led to a 60 percent drop in the rate of gun violence. He describes how the model, which he took to several other cities, has sometimes succeeded phenomenally but also how organizational politics can prevent the process from unfold-ing fully. He names names and tells tales.

A key to Kennedy’s success in changing the way the country thinks about preventing urban violence is that he is an excellent ethnographer. A keen observer and listener, he carefully considers all respondents’ points of view and works for solutions that include and benefit them all. His work is contextualized by the research and theory he knows so well, while he brings a profound emotional commitment and sense of urgency to a problem that is literally a matter of life and death.

Kennedy’s work serves as a model to Swarthmore students, as was borne out during his visit to campus in April. He listened to and spoke with Chester residents concerned about gun violence; visited a prison with Swarthmore’s Politics of Punishment class; and taught students from two seminars who had read his book as part of their semester’s coursework.

Swarthmore students are explicitly encouraged to use their knowledge, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills in the context of a deep sense of ethical concern and a commitment to positive social change.Don’t Shoot provides an exceptionally vivid and personal account of a scholar-practitioner doing just that.

—Joy Charlton,

professor of sociology and executive director of the Lang Center for Civic and Social Responsibility

Listen to Kennedy’s campus talk here

BOOKS

Heli Meltsner ’60, The Poorhouses of Massachusetts: A Cultural and Architectural History, McFarland, 2012. In this study, the author examines both the way in which the architecture of poorhouses reflected and shaped the treatment of the poor and the rise and fall of these institutions.

Heli Meltsner ’60, The Poorhouses of Massachusetts: A Cultural and Architectural History, McFarland, 2012. In this study, the author examines both the way in which the architecture of poorhouses reflected and shaped the treatment of the poor and the rise and fall of these institutions.

Palmer Brown ’41, Something for Christmas, The New York Review, 2011. After being out of print for 45 years, this book, in which a mouse tries to find a Christmas present for his mother—was republished by the New York Review Children’s Collection.

Barbara Newborg ’41, Walter Kempner and the Rice Diet: Challenging Conventional Wisdom, Carolina Academic Press, 2011. Basing this compilation on her 40 years as the chief medical associate of celebrated kidney and heart specialist Walter Kempner, the author documents Kempner’s work and unconventional research at Duke University.

Tony Holtzman ’55, The Railroad, Cloud Splitter Press, 2012. Picking up where Axton Landing left off, The Railroad is the second book in the Adirondack Trilogy, which follows the Carter family during the late 1800s as they try to cope with the changes that the creation of a railroad will bring.

Atala Dorothy Toy ’63, Nature Spirits, Spirit Guides, and Ghosts: How to Talk with and Photograph Beings of Other Realms, Quest Books, 2012. Toy provides anecdotes that feature mystical encounters and explanations of those experiences.

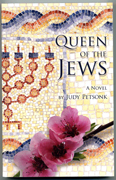

Judy Petsonk ’66, Queen of the Jews, CreateSpace, 2012. In this novel, Petsonk brings to life one of themost overlooked, female rulers of Judea—Queen Salome Alexandra—in a vivid portrayal that focuses on her relationship with her husband and her people, who called her Shalom-Zion, the peace of Zion.

Susan Jo Russell ’68, We Are Not Entirely Abandoned, Finishing Line Press, 2012. Against the backdrop of World War II, Russell’s poems present a link to the past, whether personal or through the letters of WWII wives, to show us that the title of the chapbook is not a wish, but a truth she has come to hold.

Connecting Arithmetic to Algebra, Heinemann Press, 2012, co-authored by Russell, demonstrates the computational strategies that underlie both arithmetic and algebra. This teacher’s guide is designed to help educators shape their instruction so that students are better prepared for future mathematics.

W.D. Ehrhart ’73, Dead on a High Hill: Essays on War, Literature, and Living, 2002-2012, McFarland, 2012. These 25 essays, written by Ehrhart within the past decade, range in subject matter from war to mountain gorillas to teaching poetry.

Padma Kaimal ’79, Scattered Goddesses: Travels with the Yoginis, Association for Asian Studies, Inc., 2012. After thoroughly researching 19 sculptures of goddesses from 10th century South India, the author follows the export and purchase of these items through private collectors and public museums, discovering that collecting and scattering are the same activity from different viewpoints.

Bruce Weinstein ’82, Ethical Intelligence: Five Principles for Untangling Your Toughest Problems at Work and Beyond, New World Library, 2011. Weinstein explores how ethical intelligence—the correct application of emotional intelligence—helps interpersonal relationships and offers tools to improve your ethics IQ. The book won a 2011 Silver Medal Book of the Year Award from Foreword Magazine.

Hannah Brown ’84, If I Could Tell You, Vantage Point Books, 2012. In this novel, four women, all facing the challenges of coping with autistic children, are brought together by their support group.

Diana Furchtgott-Roth ’79, Womens’ Figures: An Illustrated Guide to the Economic Progress of Women in America, AEI Press, 2012. Challenging misconceptions about women’s progress, the author illustrates how women are succeeding in closing the divide between themselves and their male counterparts in terms of education, profession, and earnings.

Diana Furchtgott-Roth ’79, Womens’ Figures: An Illustrated Guide to the Economic Progress of Women in America, AEI Press, 2012. Challenging misconceptions about women’s progress, the author illustrates how women are succeeding in closing the divide between themselves and their male counterparts in terms of education, profession, and earnings.

Heather Shumaker ’91, It’s OK Not to Share and other Renegade Rules for Raising Competent and Compassionate Kids, Tarcher/Penguin, 2012. By garnering evidence from child psychiatrists, pediatricians, educators, and her own experience, Shumaker provides a list of rules for acceptable behaviors during playtime, and most of them are not what you would expect!

Fletcher Wortmann ’09, Triggered: A Memoir of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Thomas Dune Books, 2012. Written from the perspective of the sufferer, this memoir gives a deeply personal account of the author’s journey through diagnosis, understanding, and coping with “pure-O” OCD.

Email This Page

Email This Page