A Healthy Decision?

Swarthmore Physicians, Pundits, Politicians, and Professors Share Thoughts on Health-Care Reform

A month after graduation you wouldn’t expect the second floor of Kohlberg Hall to be buzzing with activity. But on June 28, several economics professors were hunkered down in their offices, poised in anticipation.

A month after graduation you wouldn’t expect the second floor of Kohlberg Hall to be buzzing with activity. But on June 28, several economics professors were hunkered down in their offices, poised in anticipation.

It was nearing 10 a.m., the witching hour for the Supreme Court’s decision on whether or not the Affordable Care Act (ACA), popularly and somewhat derisively known as Obamacare, would live or die.

The media machine was in a race to be first out of the gate with the hot news.

Assistant Professor Erin Todd Bronchetti pulled up CNN and saw that the Roberts Court had struck down the health-care reform law. Her eyes were not sparkling with delight.

Then Bronchetti left her office to find Department Chair Ellen Magenheim smiling. “Ellen was happy, and I didn’t know why,” says Bronchetti, shaking her head.

“And I was wondering why Erin was looking so unhappy,” Magenheim counters. “I was following the SCOTUS [Supreme Court of the United States] blog,” which correctly reported the outcome, unlike CNN and Fox News.

As reality settled in, “People began reacting on the hallway,” recalls Magenheim. One colleague proclaimed how proud he was of his country. And though she wasn’t thrilled about the weakening of the law’s provision that would have required states to expand Medicaid to cover more needy Americans, “I knew overall it was good news. It was amazing to me how perilously close it was to not being upheld.”

Though it may not rank with John F. Kennedy’s assassination or 9/11 in do-you-remember-where-you-were-when-you-heard-the-news moments, for a certain segment of Americans, it ranks pretty high.

Alex Capron ’66, P’15, the Scott H. Bice Chair in Healthcare Law, Policy and Ethics at the University of Southern California, heard the news while attending a big bioethics conference in Rotterdam, The Netherlands. “When I said, ‘The Supreme Court just upheld the law,’ a huge cheer went up because the idea of universal health care is so fundamental in the rest of the world.”

Richter Professor of Political Science Carol Nackenoff, too, was in Europe on decision day, traveling by boat and bus to Dubrovnik, Croatia. “I kept waiting, but I didn’t hear about it until that night when I was sitting in a little café and pulled up the news feed.”

She accurately predicted that the court would reject the Obama administration’s claim that the clause of the Constitution that grants Congress the right to regulate commerce provided justification for the legislation. However, she expected the court to strike down the ACA by a narrow margin. Upholding the law by saying the mandate requiring Americans to obtain health insurance could fly under the tax clause was a bit of a surprise, as was the identity of the justice who zeroed in on that rationale.

legislation. However, she expected the court to strike down the ACA by a narrow margin. Upholding the law by saying the mandate requiring Americans to obtain health insurance could fly under the tax clause was a bit of a surprise, as was the identity of the justice who zeroed in on that rationale.

“It surprised me that Roberts was a key player,” says the expert in constitutional law. “But as a good chief justice, he is concerned with the perception of the court, which took a beating after the Citizens United decision [permitting corporate election spending]. If the ACA was struck down along straight party lines, it would have seemed partisan during an election year. The chief justice recognized that judicial restraint was a virtue here.”

During the six weeks after the decision, an array of policy wonks, pundits, physicians, politicians, and professors on and off campus shared with the Bulletin their reactions to the decision to uphold the law that is expected to extend medical coverage to 30 million more Americans by 2014. Some hail the ACA as significant as the Medicare law that President Lyndon B. Johnson signed 47 summers ago.

Let’s start with Michael Dukakis ’55, one-time Democratic nominee for president, former governor of Massachusetts, and a warhorse for decades in the fight to craft a better health-care system for the American people. These days, Dukakis is far from the madding crowd, in a modestly appointed corner office on the campus of Boston’s Northeastern University, where he’s taught for 21 years. This summer, he’s teaching a course on health-care law.

The Supreme Court’s decision surprised him, he says, “because I thought that the commerce clause was more than enough to justify the bill. I never anticipated the [ruling on] Medicaid [expansion], which really comes out of the blue. Not a single one of the courts of appeal, who disagreed on the subject of the individual mandate, raised the Medicaid question, which tells you something.”

While he finds that aspect of the decision troubling, he asserts, “It’s a landmark bill, no question about it. Remember, this is the fourth president who’s tried it and the only one who’s succeeded: Truman, who couldn’t get his essentially universal Medicare bill through; Nixon, who couldn’t get his bill through; Clinton who couldn’t get his bill through. This president [Obama] was able to make it happen.”

That’s a point that resonates with Rick Valelly ’75, Claude C. Smith ’14 Professor of Political Science, who teaches courses on national politics and elections. He takes a break from his sabbatical research to meet in his sunny office on the second floor of Trotter Hall.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, in fact, he says, considered universal health care in the New Deal days but declined to pursue it. When the ACA was passed by Congress in 2010, “the Democratic Party delivered on something it had wanted to do since 1935,” says Valelly. “It was a major turning point in the evolution of this country. Obama saw in the individual mandate the key that would pick the lock [on health-care reform].”

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, in fact, he says, considered universal health care in the New Deal days but declined to pursue it. When the ACA was passed by Congress in 2010, “the Democratic Party delivered on something it had wanted to do since 1935,” says Valelly. “It was a major turning point in the evolution of this country. Obama saw in the individual mandate the key that would pick the lock [on health-care reform].”

Sen. Carl Levin ’56 (D–Mich.), who followed Dukakis as chair of Students for Democratic Action at Swarthmore, also regards the ACA as “absolutely a landmark decision. It’s where we should have been like every other advanced economy long ago, which was making sure all had health care. We’ve paid a heavy price not just in terms of health but in terms of efficiency of the system, where millions of people who don’t have any health coverage use emergency rooms for nonemergency purposes.”

As for the part of the decision that allows states to decline Medicaid expansion, Levin says, “Those states that opt out are being foolish. I don’t know how those Republican governors can justify saying no to additional coverage for their people, when the federal government is paying for it [at the rate of 100 percent for 2014–2016 and 90 percent thereafter].”

Though Levin concedes that the mandate that all Americans must obtain health care or pay a penalty is not popular—56 percent of respondents to a March CBS poll opposed it—other aspects are cheered by a majority, he says. These include mandatory coverage of persons with pre-existing conditions, coverage of persons under age 26 on their parents’ plans, discounts that reduce the Medicare prescription drug coverage gap, and coverage of preventative diagnostics like mammograms. “Over time, the term Obamacare will translate into what I saw recently on a bumper sticker: Obama Cares,” Levin says.

Down the hall from Rick Valelly’s office in Trotter, his colleague Nackenoff is less convinced that the bill was monumental, though she does note that, “historically, health care has been one of the most difficult things to legislate in the United States. It brings out the rhetoric of class warfare—the haves and the have-nots.” Due to the polarizing nature of the subject, she’s concerned that a law that most individuals concede has serious flaws will not be improved any time soon. “For Obama, will trying to improve the law be a priority? It’s wise not to do so if he wants to be re-elected.”

What would have been monumental, Nackenoff, suggests, “is if the Supreme Court had struck it down.” That would have been an affront to the ability of Congress and the president to shape the laws of the nation, she feels.

Down Washington way, Diana Furchtgott-Roth ’79, an economist for the Reagan and both Bush administrations who’s now a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and frequent commentator on economic issues, voices her surprise at the decision.

“As a tax economist, it never seemed to me to be like a tax, and it wasn’t described as a tax in the bill. It was described as a penalty. Even now, after the Supreme Court decision, the White House is saying it’s not a tax.”

In her elegant English accent, she does not mince words: “I do not think it was a good decision.”

She explains that, due to the low tax penalty for noncompliers—$95 in 2014, $350 in 2015, $750 in 2016—compared to the high cost of insurance coverage—about $12,000 per year for a family—the law has no teeth. “The Supreme Court’s decision by calling it a tax makes it perfectly legal to pay and then not sign up for health insurance.”

She also contends that the Internal Revenue Service has limited power to enforce collection.

Due to these and other deficiencies, Furchtgott-Roth says, “I don’t think the law will stay intact. People are already chipping away at it. The law is unworkable and unequal. The well-off people are going to go outside”— and purchase concierge types of services creating a two-tier health system similar to the one she experienced as a child in Great Britain, she says.

Furchtgott-Roth has plenty of ideas on how to improve the ACA. “Get rid of the concept of the qualified benefit plan that has the mandatory mental health, drug abuse, contraception, and no co-pay per visit. Instead, allow any kind of health policy on the exchanges”—marketplaces, where people not covered through their employers would shop for health insurance at competitive rates. This linchpin of the ACA requires all states to set up exchanges by 2014.

One tweak to the ACA she hopes never to see is adoption of a single-payer system—medical care funded from a single, government-run plan—which she experienced in England. When her grandmother had a stroke on a Friday, she was told the doctor couldn’t see her until Tuesday. “I said, ‘Can’t I pay to have the doctor come in over the weekend?’ ” The answer was no. “Rationing that will go with a single-payer system is not going to go over with many people.”

But rationing is already alive, well, and kicking in our health system, claims physician/senator Joshua Green ’92, who held forth recently on the ACA from his home on Hawaii’s Big Island.

“We do ration care in America. Unfortunately, the rationing is based on wealth,” he says. “I would like to see a system where people get emergency and basic health care no matter what. I know Americans like choice. The question is, do we also choose to provide basic health care for everybody, which is the civilized thing to do? Doing so is good for the national psyche.”

Green has a unique perspective on reform, since he is not only an emergency-room physician and family practitioner but also chair of his state’s Senate Health Committee and medical director of the 800-member Hawaii Independent Physicians Association (HIPA).

“It’s tiring, but I decided to remain a full-time physician as well as a policy person—otherwise my credibility goes through the floor. I want to inform some of the policy concepts with my actual clinical experience.”

His state, which already covers 92 percent of its residents, is regarded as “the closest state in the country to having universal health care,” since anyone who works half time is covered by his or her employer, and the state offers health care that “is more affordable than any state in the country,” he says.

Hawaii also is a leader in cooperating with health insurers, he says, noting that HIPA partners with Blue Cross, which insures 75 percent of Hawaiians.

Hawaii is in the midst of setting up its health-insurance exchange, as required by the ACA. According to Green, regional exchanges—say Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Delaware constituting one region—rather than exchanges that are bound by state lines, will be essential to providing consumers more choice. “They’ll find better fits for themselves, and that should drive down costs.”

However, he cautions, “The Affordable Care Act will only work if we renew our commitment to primary care. We need to get family physicians and nurse practitioners into every community in America. If we don’t, the rest is just noise.”

Fortunately, he says, there are a lot of provisions for prevention, wellness, and primary care in the ACA. “Rather than having the expectation that people should spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on surgeries and advanced tests at the end of life, spend health dollars during the 40s and 50s to keep good health for the future.”

Green’s fellow West Coaster, USC’s bioethicist Alex Capron ’66, also feels that the emphasis on primary care and formation of provider groups that are patient centered are keys to health-reform success.

Capron notes that central Pennsylvania’s Geisinger Medical Center, a patient-centered system that was, along with the Mayo Clinic, considered a model for accountable-care organizations by the ACA architects, is a good example.

“Physicians there see that the work they’re doing leads to better results, which actually allows them to have more time with each patient, rather than the fee-for-service model where doctors see patients [briefly] and move ’em out.”

The ACA, Capron says, “also has the potential to mend one of the deficiencies in existing care, which is barriers to communication. From a medical-ethics point of view, we should have more encouragement for conversation, where physicians share more of their thinking with patients. More shared decision making is a central idea of bioethics.”

Ethics also is top of mind for Bruce Weinstein ’82, a New York-based ethics blogger at Bloomsberg Business Week and author who often appears on cable and network television as a commentator on ethics. A couple of years ago, in a discussion of health care on Fox Business’s Varney & Co., host Stuart Varney accused him of being a socialist.

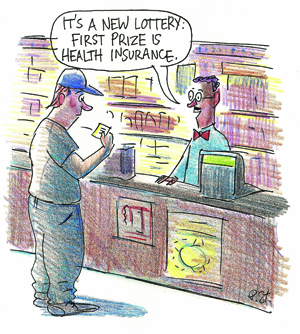

“It was an unethical attack, playing into the fear of an audience that doesn’t understand what the word means,” he says. “They’re forgetting that a lot of institutions in this country could be called socialist: road repair, libraries, public schools. Unless your ideal is to privatize everything and make sure we’re at the mercy of the free market … But the free market approach has not worked. Every year more and more Americans are uninsured—32 million in the ’90s, now up to 50 million. The free market is just not taking care of it.”

By spouting invectives like “socialism,” people are using language as a smokescreen, he says, “providing more heat than light.”

Clear language, however, has been lacking in the health-care debate, according to Weinstein. “The main problem with the law is that the president hasn’t done a good job of explaining what it means. I believe there should be no idea or law or policy so complicated that the essence cannot be simply presented.”

Clear language, however, has been lacking in the health-care debate, according to Weinstein. “The main problem with the law is that the president hasn’t done a good job of explaining what it means. I believe there should be no idea or law or policy so complicated that the essence cannot be simply presented.”

Nackenoff agrees that “the administration could do a better job, admit that this law has a lot of warts—it’s not a prince, it’s not quite a frog. The administstration has to sell the vision better than it’s doing.”

Dukakis gives that notion a nod. What the Democrats have, as Boss stated immortally in Cool Hand Luke, “is a failure to communicate.”

“The failure of the Democrats to [properly] frame the health-care issue bothers me,” he says. “It’s not about pre-existing conditions and keeping your kids on the policy until age 26. Those are interesting details. But it’s about whether or not working Americans and their families can afford decent health care. That’s the issue, but we haven’t been saying that. People think it’s another welfare program, that we’re taking money from you to give to one of those folks, right? It’s not that at all. If it really is about working people and their families and you don’t say that, don’t be surprised if working folks don’t vote for you.”

On the contrary, Valelly believes the clarity of the message is not the problem. “People think the president can change people’s minds. But if you take a look at people’s opinions on public policy after a presidential address, you’ll see little change. If there is any, it disappears within two weeks. So that’s a myth that if only the president could explain the message it will get through. Opinion will change once the law begins to phase in. It doesn’t fully phase in til 2016. In a decade, people will definitely be in favor of it.”

As for an eventual Medicare-for-all approach, which President Bill Clinton tried and failed to implement, Valelly is skeptical. “The Obama administration studied what went wrong with the Clinton plan and neutralized the opposition of the insurance companies [by inviting them in].”

Though the Medicare-for-all approach failed to gain traction in the past, Oliver Fein ’62, a professor of clinical medicine and clinical public health at Weill Medical College of Cornell University, still holds out hope for a single-payer option.

“I think the limitations that are inherent in the ACA will become apparent,” he predicts. “It’s calculated by the CBO [Congressional Budget Office] that 26 million people will remain uninsured in 2019. In that sense, it doesn’t bring us truly to universal coverage. Second, there are very inadequate means to control the cost of health care in the ACA. From my perspective, a single-payer approach, a situation in which Medicare was improved and expanded to cover everyone in this country—has the best chance to guarantee universal coverage and has the greatest potential to control costs. Overhead and profit for Medicare is 3 percent, whereas in private insurance it’s 20 to 30 percent.”

As chair of the New York Metro Chapter of Physicians for a National Health Program, for which he served as national president in 2009–10, Fein advocates actively for a national health program by discussing it at grand rounds, speaking to community and church groups and appearing on programs such as Democracy Now and The O’Reilly Factor.

He’s not shy about saying he doesn’t think the ACA will solve the health-care crisis in this country, though he champions the fact that “it’s the first time Congress has said there ought to be universal access to health care and that the federal government has some responsibility in guaranteeing that right. As Martin Luther King Jr. said, ‘The arc of history bends toward justice.’ Perhaps the ACA suggests that the arc of history bends toward universal access to health care.”

Email This Page

Email This Page