Let's Talk About It

Is Swarthmore a model for improving our national conversation?

ON A SUNNY MONDAY IN APRIL, OPPOSITE THE doors of Parrish Hall, a group called Students for Peace and Justice in Palestine (SPJP) erected a 10-foot tall fence covered in black plastic. With a narrow opening at its center, topped with barbed wire, it mimicked an Israeli checkpoint. People who wanted to experience the mock checkpoint were stopped and searched by students wearing t-shirts labeled “IDF” or “International Observer.” Some were allowed through; others were arbitrarily refused entrance. The first part of a series of events and discussions called “Three Days in Palestine,” it was intended to raise awareness of the plight of Palestinians in Israel and the occupied territories. Not surprisingly, it also provoked a host of reactions, some of them quite negative. Yet, postings on the student online Daily Gazette—where campus debates seem to be aired these days—were mostly respectful and thoughtful.

ON A SUNNY MONDAY IN APRIL, OPPOSITE THE doors of Parrish Hall, a group called Students for Peace and Justice in Palestine (SPJP) erected a 10-foot tall fence covered in black plastic. With a narrow opening at its center, topped with barbed wire, it mimicked an Israeli checkpoint. People who wanted to experience the mock checkpoint were stopped and searched by students wearing t-shirts labeled “IDF” or “International Observer.” Some were allowed through; others were arbitrarily refused entrance. The first part of a series of events and discussions called “Three Days in Palestine,” it was intended to raise awareness of the plight of Palestinians in Israel and the occupied territories. Not surprisingly, it also provoked a host of reactions, some of them quite negative. Yet, postings on the student online Daily Gazette—where campus debates seem to be aired these days—were mostly respectful and thoughtful.

“[I]t was decided among many present at discussions within the Jewish community that we wanted to respect the protest of the wall,” wrote one student. “To have a counter protest or provide information separately from SPJP’s event was thought to be an encroachment of another group’s space.”

Another student wrote: “I might not support your opinion on the issue, but I would certainly defend your right to express it on campus and would criticize anyone who would strip you of that right.”

This kind of open-mindedness is sorely lacking in national discourse these days. In federal, state, and local politics; schools; places of worship; the media—even within families—debates on policy, morality, and ethics have devolved into an uncivil war between the right and the left. Attempts at earnest dialogue are too often met with suspicion and drowned out by clamorous rhetoric and vilification. Opposing viewpoints are shouted down or mocked. Threats of violence are made by some and silently condoned by others. Rather than being a rich asset of democracy, differences of opinion are a source of bitter division.

At one point in the three-day spate of Daily Gazette comments, an anonymous parent blasted Swarthmore for, among other things, allowing “extremism” on campus. Stephanie Appiah ’10 responded: “We’re still getting roadblocks in the conversation, because so much time is spent insulting people who post questions instead of constructively answering their concerns. The point of [these] comments is not to ‘win’ or to make the previous commenter look stupid. It’s to broaden the conversation, but that doesn’t seem to be happening.”

Swarthmore has long prided itself on being a community willing to engage with controversial questions in a civil manner. It’s been part of the College’s institutional identity since its founding in 1864: abolition, women’s suffrage, pacifism, communism, free speech, wars, civil rights, gay rights, women’s liberation, apartheid, a woman’s right to choose abortion, and a host of other complex issues, including the Arab-Israeli conflict, have been the focus of campus activism and debate. New campus groups are constantly forming to address local, national, and international issues. Classroom discussions turn into late-night debates in the dorms. Fiery letters in The Phoenix, provocative posters on Parrish Hall bulletin boards, and impassioned comments in The Daily Gazette have all been a training ground for generations of Swarthmoreans honing their skills at persuasion, dissent, and discourse.

“Student activism is very important on campus,” says Natalie Litton ’12. “At Swarthmore, arguing is the norm. But unlike what’s going on in the world outside the bubble of Swarthmore, we have a little cushioning. When it gets too contentious, a dean will say, ‘Calm down, and let’s have a discussion.’”

Darryl Smaw, associate dean for multicultural affairs, did indeed send an e-mail to the student body the day after the SPJP’s wall went up. He wrote: “I hope that you will take this time to engage one another in a form of respectful, civil dialogue that has, as its main purpose, a desire to listen earnestly and hear the multiple sides of an issue. I also hope that as you talk to each other, you will engage less in debating the ‘pros’ and ‘cons’ and instead open yourself to an honest dialogue about the complexities of this issue from each perspective.”

Even those who graduated from Swarthmore decades ago can hear in Smaw’s words the echoes of past deans exhorting tolerance for diverse viewpoints. If there is one unifying theme that defines the “Swarthmore experience,” it may be this: Along with acquiring knowledge through scholarship, we also absorb the value of civil discourse.

“CIVIL DISCOURSE” ESSENTIALLY MEANS ENGAGEMENT IN CONVERSATIONS intended to enhance understanding. What it actually looks and sounds like can vary according to a person’s background, culture, and personal style as well as the wider social and political context, says Lee Smithey, assistant professor of sociology and coordinator of the Peace and Conflict Studies Program. For some, civil discourse might be dispassionate, measured speech and polite listening. For others, it might mean contributing to public debate through public demonstration.

Smithey, whose work focuses on the conflict in Northern Ireland, says one measure of the civility of discourse is the extent to which it enhances, or at least preserves, the possibility of further constructive dialogue and cooperation. “We can also ask ourselves whether we are open to persuasion and compromise even as we speak with conviction.” He also proposes that civil discourse includes “being able to be honest about my position even when an issue makes me so angry that my throat clenches up and tears roll down my face. And ideally, in a civil dialogue, we have space to change our positions without being considered inauthentic.”

That last point resonates with Litton. “Swarthmore is a comfortable place to think. You don’t need to show up in class or seminar with a fully developed position. You just have to be ready to discuss whatever stage your opinion is in at that moment.” There’s a certain acceptance and expectation that students are still figuring things out and that complex issues aren’t black or white, yes or no, moral or immoral.

“Acknowledging complexity—the gray areas—creates more civility and more curiosity,” she says. “Professors and other students genuinely want to know why you think a certain way about an issue.”

Economist Dean Baker ’80, who taught at two large universities early in his career, remembers being taken aback when his students constantly asked him, “Will this be on the exam?”

“That never happened at Swarthmore,” he recalls. “We were actually trying to learn the material because it was valuable. Asking that question implied that you wouldn’t know for yourself what was important—that you’d need someone to tell you what to think. In philosophy class with Richie Schuldenfrei [professor emeritus of philosophy], he would harass you if he thought you were saying something just to be agreeable. He wanted us to think for ourselves, not parrot back what we thought he wanted us to think.”

When Julie Schwendiman Crockett ’99 started the group Swarthmore Students Advocating Life, she had difficulty identifying a faculty member who was openly pro-life to serve as the group’s adviser.

“The faculty restrain themselves from voicing their opinions on issues, which I think is a good thing,” she says, “because it gives students space to decide about issues for themselves.”

She was also impressed by how the administration modeled open-mindedness. She and members of the group went to see then-dean of students Robert “Bob” Gross ’62 to consult with him about a pro-life event on campus. “As we left, he told us, ‘Thank you for keeping the rest of us from becoming mushy-minded liberals.’ ”

SWARTHMORE'S OPERATING ASSUMPTION HAS BEEN that exposing young people to diverse perspectives will help them become not only more knowledgeable and informed but also more tolerant and empathic. Of course, it doesn’t always work out that way. There are plenty of examples of disagreement being expressed in hostile and hurtful ways.

Kevin Kuehlwein ’83, a cognitive psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania’s medical school, remembers during his junior year, when the Gay/Lesbian Union asked students to wear jeans on a certain day to show their support. That day, someone set a pair of jeans on fire, which led to a storm of letters in The Phoenix in support of and against homosexuality.

On a small campus like Swarthmore’s, students are quick to speak out against what they perceive as intolerance, says Joyce Tompkins, Protestant religious adviser and interfaith coordinator. During Coming Out Week in 2009, anonymous chalkings appeared on Magill Walk condemning homosexuality by quoting from Scripture. “Students from both campus Christian groups—Swarthmore Progressive Christians and Swarthmore Christian Fellowship—were upset that someone apparently Christian had done something so hateful,” says Tompkins. “Their solution was to go and chalk other Scripture passages that basically said, ‘God is loving and welcomes you as you are.’”

“You can’t force anyone to be open-minded,” says Kuehlwein. “For there to be civil discourse, people need to be willing to show a certain amount of respect for others; realize that reasonable people can have differing opinions; and realize that it’s a good idea to listen. Although it didn’t happen all the time, there was an overall feeling that the community supported that level of communication.”

RACISM HAS LONG BEEN A CONTROVERSIAL TOPIC on campus. In 1990, following diversity trainings in the dorms by student facilitators—some were led more skillfully than others—notes were posted in Parrish Parlors next to paintings of college founders and presidents, asking, “How come there ain’t no brothers and sisters on these walls?” A note on a mirror read: “Is this mirror the only way you are represented on these walls?”

Weeks of intense, but relatively civil, campuswide discussions about diversity and affirmative action followed. But then an anonymous letter in The Phoenix right before winter break changed the tone: “This issue is entirely ridiculous. When will you minorities (blacks) stop feeling sorry for yourselves and shut up? … What about us Caucasians who could not go to certain schools or attend summer programs because such places offered only minority scholarships? Where is our culture? Do you expect us to throw it out the window?”

The hostility escalated a few weeks into the next semester, when a student’s painting of Malcolm X, which had been hanging in the hallway of Parrish, was slashed and left on the floor with a length of rope. Days later, most of the College’s African-American students walked out of a Collection organized by Student Council to air the issue.

Then–Assistant Dean Joseph Mason, who was director of the Black Cultural Center, wrote in the May 1991 Bulletin: “Racially divisive attitudes are a reality in our society, and Swarthmore—despite its ideals—is not exempt from such pain and ugliness…. The challenge ahead is to use our intelligence and academic prowess to deal with these attitudes in constructive rather than destructive ways.”

A COMMUNITY ETHIC THAT VALUES DIVERSITY, an administration that promotes (and enforces) tolerance, and an academic standard that acknowledges complexity and requires critical thinking weigh the scale in favor of civil discourse. Yet, there are many other factors that affect the process. Negative emotions such as fear, anger, and anxiety limit our cognitive capacity. When we experience these negative moods and emotions, our brains actually lose the ability to think rationally and process information properly, says Etsuko Hoshino-Browne, assistant professor of psychology. “Feeling anger, a person may become intolerant and close-minded to other political views,” she says, “while at the same time he or she might feel even more strongly that his or her own group is moral, superior, or correct—and that the other group is wrong, immoral or even less than fully human.”

Although it may be difficult to convince people to value open-mindedness, it is possible to make people aware that it’s their choice whether or not to be open-minded. Hoshino-Browne studies and teaches the psychology of prejudice, and she says that even though it’s human nature to become defensive when we encounter something we don’t agree with, we have tremendous cognitive control over whether or not we suppress our defensiveness and stay open-minded.

But why would a person choose the uncertainty of open-mindedness over the more comfortable position of absolute certainty? Hoshino-Browne contends that everyone has experienced both sides of prejudice—victim and perpetrator. She models for students how to examine their sometimes hidden prejudices by sharing her personal experiences of judging others negatively based on their group affiliation and profession. “Because we are motivated to believe that we are fair-minded and egalitarian, we often become defensive when we face our own, deep-seated prejudices,” she says. “We can reduce prejudice by cultivating empathy and the ability to entertain others’ perspectives. Numerous studies find that these two factors correlate strongly with one another, and intuitively, these factors should be conducive to open-mindedness in high-conflict situations.”

Without the ability to entertain another person’s perspective, it becomes easy to objectify and demonize those who hold different beliefs—or who look different, act differently, or have different life experiences. As America’s political divisions widen, it’s become easier to dismiss the other side as “those right-wing nuts” or “those unpatriotic liberals” (and worse). And because most people’s social networks act as a kind of echo chamber, such verbal potshots tend to go unchallenged.

Litton became aware of this when Sarah Palin’s book, Going Rogue, came out last fall. Her liberal friends sent around a slew of e-mails making cracks about the former Alaskan governor’s book. Litton was about to chime in, but then stopped herself. She realized that in all fairness, she should read the book before she judged it.

Litton went to McCabe Library to check out Palin’s book. The student at the circulation desk gave her a confused look. “He knew I’d just been elected president of the Young Democrats,” Litton explains. “He couldn’t believe I’d want to read Palin’s book!” The responses she got walking around campus with the book amazed her. “People were shocked that I was reading it.” But it was only by reading Going Rogue that Litton felt she’d earned the right to criticize it.

MUCH OF THE POLITICAL POSTURING going on right now in American politics plays to emotions rather than fact, says Kuehlwein, a political liberal. “Swarthmore imbued us with a respect for the fact that truth is complicated and intellectual rigor is important. But what passes for political debate these days is often a very manipulative framing of the terms. For example: Death Panels. Socialized Medicine. Tax Relief. The facts are superseded by the emotional valence of the terms.” People become afraid, and then, says Kuehlwein, they engage in destructive behaviors like labeling, over-generalizing, catastrophizing, and bullying, which further constrict their thinking and openness to other people’s views and experiences.

The late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan once said, “Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not his own facts.” As a student, Russ Ferrell ’54, watched the Army-McCarthy hearings with great dismay with fellow students on a television at a local pizza joint during the honors exam period. To Ferrell, having the backbone to stand up for the facts is a vital part of civil discourse. “At Swarthmore, we had to have the facts,” he says. “That was the whole point of education.”

Ferrell, a retired professor of systems and industrial engineering at the University of Arizona—and a self-described political radical—says it’s very difficult to stay civil with people who insist that the world is a certain way and ignore the facts, or who make up facts to fit their world view. A practicing Quaker, he believes it’s important to confront people—nonviolently, of course—who may have gotten their facts wrong.

But Matthew Schenk ’95, a founder of the Swarthmore Conservative Union, points out that having the facts and being open-minded won’t necessarily turn a person into a liberal. “Swarthmore made me a critical thinker and helped me analyze problems from multiple angles,” he says. “I also learned to separate the personal from the political—I could radically disagree with people and still be good friends with them. But Swarthmore didn’t change my views on gay rights, economic policy, or abortion.”

It certainly didn’t turn him into a liberal or a Democrat. Schenk’s company, HSP Direct, raises money for conservative groups, including Sarah Palin’s political action committee. In the lobby of his office, FOX News plays on the television throughout the day.

“Just because I have opinions I strongly believe in doesn’t mean I’m not open-minded,” says Schenk. “I don’t support gay marriage, but I don’t think gay people are evil. You can’t paint anyone of any group in broad stripes. And I hope, meeting me, people realize that conservatives can’t be placed into a narrow box of greedy warmongers.”

It was different for Hillary Abbott Thompson ’99, now a graduate student in political science at Boston College. She was among a handful of conservative activists on campus in the late 1990s, and she also became close friends with the leaders of the Young Democrats. Thompson spent countless hours debating social, political, and economic policies with them. After Swarthmore, she discovered that other conservatives considered her to be a liberal because of her pro-gay and pro-choice positions. “Swarthmore made me an open-minded, militant moderate,” she says with a laugh. A registered independent, she voted for Obama.

On the other end of the political spectrum, Dean Baker ’80, co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research and a self-identified progressive, recently collaborated on an op-ed piece with Kevin Hassett ’83, who works at the conservative American Enterprise Institute. “I try to be open-minded and evaluate ideas without prejudice,” Baker says. “I’ve learned to listen to what conservatives are saying rather than just dismissing them all as extremists. Even though Kevin and I are ordinarily on the opposite sides of many issues, there are areas where he makes points I can agree with.”

Outside the bubble of Swarthmore, in the maelstrom of Fox News versus CNN, the national conversation is marinating in bitter sound bites and wild conspiracy theories. The skills of civil discourse are sorely lacking, and Americans seem to have lost the ability to consider both sides of an issue. Hillary Thompson likes to think that the country is still capable of engaging in mutually respectful dialogue. “I don’t know if it’s really possible,” she admits, “but it was possible at Swarthmore.”

Laura Markowitz '85 (right) is a writer and contributing producer for Arizona Public Media, Tucson’s NPR and PBS affiliates, and chairs the Swarthmore College Tucson Connection.

Laura Markowitz '85 (right) is a writer and contributing producer for Arizona Public Media, Tucson’s NPR and PBS affiliates, and chairs the Swarthmore College Tucson Connection.

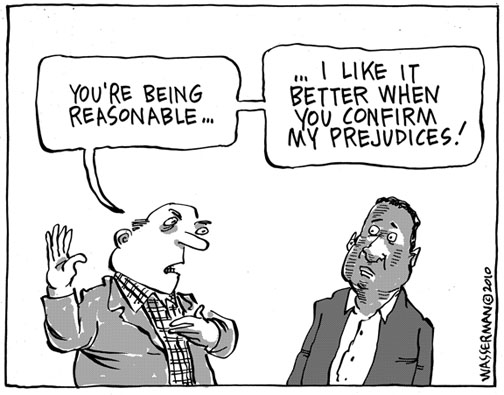

Dan Wasserman ’71 (left) has been a cartoonist for The Boston Globe since 1985. A former employee at The Washington Star, his work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, The Economist and The Wall Street Journal and is syndicated to about 40 newspapers internationally. He has published two cartoon collections. Read his blog at www.boston.com/wasserman.

Dan Wasserman ’71 (left) has been a cartoonist for The Boston Globe since 1985. A former employee at The Washington Star, his work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, The Economist and The Wall Street Journal and is syndicated to about 40 newspapers internationally. He has published two cartoon collections. Read his blog at www.boston.com/wasserman.

Email This Page

Email This Page

July 9th, 2010 1:43 pm

Very insightful article that shows how Swarthmores students can learn and grow from diversity and tolerance

September 1st, 2010 12:33 pm

Great article. Swarthmore students should always value diversity and tolerance. It is the only way for the country given the polarisation that has taken place these days.