Too Important to Die

A Short Tale About How a Long-Buried Book Finally Saw the Light

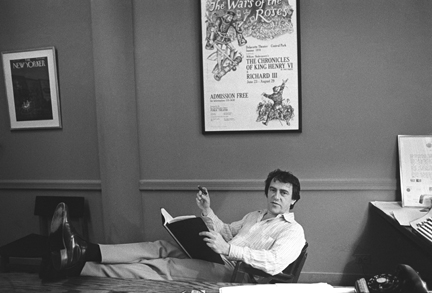

Before he died, famed producer Joseph Papp (above) stood in the way of the completion of Kenneth Turan’s oral history of the New York Shakespeare Festival and Public Theater. The book has now been published.

More than 23 years ago, I signed a contract with famed theater producer Joseph Papp to work on a definitive oral history of the New York Shakespeare Festival/Public Theater, the most significant not-for-profit theater group in the country. During the next 18 months, I interviewed close to 160 people and turned nearly 10,000 pages of transcript into a roughly 1,100-page manuscript. I considered it then—and still consider it today—to be the most significant and compelling work I’ve done in more than 40 years of journalism. The story of why something with so much to recommend it would take so many years to reach print is, in some ways, as dramatic and surprising as the book itself*.

In his years with the Shakespeare Festival and the parallel Public Theater, Joe made theater in America both accessible and essential. He’d produced landmark plays like Hair, A Chorus Line, That Championship Season, The Normal Heart, and Short Eyes—plays that people had to pay attention to because they transcended their moment in time.

Papp had been essential in launching the careers of actors like George C. Scott, Meryl Streep, Raul Julia, Kevin Kline, James Earl Jones, and Martin Sheen. He’d had towering disputes with everyone from New York City’s all-powerful bureaucrat Robert Moses to the very playwrights and actors he hired, but almost everyone ended up doing their best work for him. When he died, The New York Times, noting the more than 350 plays he’d brought to the stage, called him “one of the most influential producers in the history of the American theater.” He was larger than life just by being himself.

The book’s interviews were mesmerizing. I have strong memories of listening to Tommy Lee Jones calmly dissect what went wrong with True West while he meticulously brushed down a horse at his remote California ranch. I remember taking the train to Connecticut to spend long hours with David Rabe as he talked thoroughly and thoughtfully about his enormously complicated dealings with Joe. And I’m unlikely to forget flying to Scranton, Pa., to interview Jason Miller, who took me straight from the airport to a raucous social club that seemed right out of That Championship Season. When I tentatively commented on the resemblance, he grinned, shot me a look from his dark, intense eyes, and said, “Are you kidding? This is the play!”

And then there was Joe himself, who both disliked taking time to talk about the past when he could be working on some future project and recognized his obligation to do so. As the veteran of innumerable battles and clashes of will (“If I were estranged from all the people I had arguments with,” he told playwright Lawrence Kornfeld, “I’d have nobody to talk to.”), he was reticent about nothing he’d been through, no matter how upsetting the memory, once he sat down to talk.

The only exception to that were stories about the difficult poverty of his childhood, which, along with the youthful radicalism it led to, was critical in informing the decisions he made and the kinds of institutions he was determined to build. After one Saturday session in his Greenwich Village apartment talking about that painful period, Joe walked me to the door, looked at me, and said quietly: “I’m never talking about that again.” He didn’t just mean to me, he meant to anyone.

Working with Joe on a project of this scope was enormously exciting, but from time to time I also feared that—as had happened with others he’d worked closely with—a rift would develop between us. And once he read the manuscript, that is exactly what happened, with a vengeance. Disturbed and troubled, Joe refused to allow the book to be published.

Even two decades later, I’m not completely sure how the factors involved in that decision coalesced in Joe’s mind. In part, he was upset by some of the things the people he’d fallen out with said about him, but the reality is that I handed in an overly long and likely repetitive first draft, and with the usual give and take of the editing process, much of that material would not have made it into the final draft.

Equally important was a horrible accident of bad timing. At roughly the same time as the manuscript was completed, Joe learned that his son Tony had contracted AIDS and that he himself had been diagnosed with the prostate cancer that was to kill him three years later.

The book’s cancellation was devastating, not only because of the work put into the project but also because of how important I felt it was to tell Joe’s story. The blow was so severe that I had difficulty talking about what transpired for years after it happened.

Though I was, of course, angry, I found that my anger was never directed at Joe. He was simply being who I had discovered him to be during my research and interviews, and in my heart I could not fault him for that.

Finally, perhaps a dozen years after the fact, I sat down on the porch of a house on Vashon Island, Wash., and wrote a letter to Gail Merrifield Papp, Joe’s widow and collaborator—and a woman whose clear vision and integrity I had always admired and respected. This project, I said, was too important to die. Was there not some way we could bring it back to life?

Gail thought perhaps there was, and what followed was a series of meetings over several years during which we discussed the manuscript and its future. More than any other factor, it was Gail’s belief that brought the project back to life. I was so encouraged that—in a guest house on Kauai—I took a deep breath and reread what I’d written from front to back, something that had been too painful to do for all those years. The thoughts I had then led to more discussions with Gail and, finally, in 2006, to a month spent at the MacDowell Colony in New Hampshire where a new draft of the book was put together.

The isolation and total immersion of the MacDowell experience, the way self-imposed seclusion encourages you to go deeper than you thought possible into your own work, was critical to getting a new perspective on the manuscript.

Sitting all alone in my tiny cabin in the New Hampshire woods, I increasingly felt not the sense of personal aggrievement about this book that had been part of my life for too long, but rather the weight of history, the powerful responsibility I had to the people who had talked to me at such length. All alone in the woods, I sometimes found myself in tears at the thought of those people—Joe first among them—who had been painfully honest about the most significant events of their lives and counted on me to relay their last testament to the world.

Roughly 40 of the people whose voices are in this book—one out of every four—have died in the two decades since I did the interviews. No one else will hear their stories from their lips, and to read this book is to re-enter, as if by magic, a moment in history ripe for rediscovery and amazement.

*Free for All: Joe Papp, the Public, and the Greatest Theater Story Ever Told by Kenneth Turan and Joseph Papp (Doubleday, New York, 2009)

Email This Page

Email This Page