Is It a Book? Is It an Artwork? Yes! It's Book Art (VIDEO)

McCabe Library’s Rare Book Room harbors a trove of whimsical artists’ books

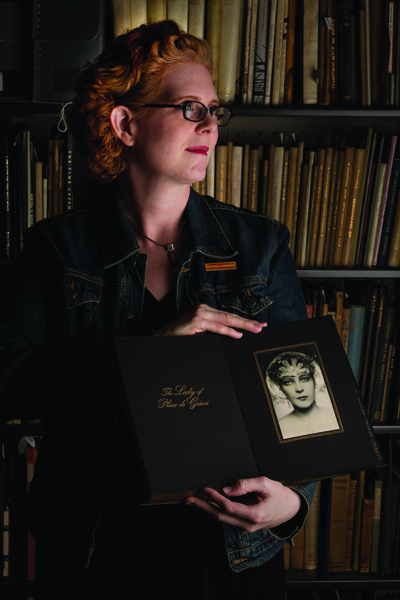

Curator of the book arts collection Anne Garrison enjoys showing visitors artists’ books, such as Maureen Cummins’ Femmes Fatales, a series of photographs of seductive yet dangerous women whose names, like “Dame Guillotine” and “The Bride of Nuremberg,” describe instruments of torture. Photos by Laurence Kesterson.

Swarthmore’s Rare Book Room exudes all the mystery of a treasure chamber. It’s really difficult to find,undefined behind a locked wooden door at the end of a short, dark hallway on the top floor of McCabe Library. You need permission to enter. Anne Garrison, the humanities and book-arts librarian and curator of the book-arts collection since 2004, is the genie who lets you in. Dimly lit, with few windows—to protect the fragile works from light damage—and smelling pleasantly of old paper, the Rare Book Room is a magical place filled with spellbinding books. Some are centuries old, others not so old. Some are in disguise or even shape-shifters.

A book titled Garden Library lies on a small, cluttered table. It has a bright cover onto which botanical illustrations and text on gardens and books have been pasted. It’s lovely to look at, but it’s when you open the book that the magic happens: A fountain of decorative paper strips—mostly white, some colored—containing lines of garden-related text, bursts out at you. Garden Library, published in 1996 in an edition of 10, is a mixed-media sculptural book by calligrapher and book artist Jan Owen. Swarthmore’s Book Arts and Private Press Collection currently comprises more than 6,000 items from almost 1,000 presses.

The task of defining book art or artists’ books is tricky, because their individual forms are each the product of the creator’s whimsy. Book artist Angela Lorenz describes them as works of contemporary art whose creation involves a number of processes. In its final form, each work usually presents a multilevel, multimedia object, access to which often requires a certain amount of effort from the “reader”—such as opening a box, undoing a fastener, or retrieving a page or note from a paper pocket. Sometimes, a text might be camouflaged by its intermingling with a completely different text.

According to Garrison, the best form of book art is when “form and content are completely cohesive and present one beautiful object.” Artists’ books are recognized as a form of art. They are typically hand bound or handmade, with an edition ranging from a few to just one. Reflecting solely the vision of their creators, they are unadulterated by either publishers or editors.

In her cozy office in a back corner of McCabe’s first floor, Garrison points to a potential new acquisition on her desk: Fresh Apple: Garden of Eden, a perfectly formed apple, crafted from pages of text pulped into papier-mâché, lies on torn-up paper strips in a small, wooden crate. The temptation to touch the silky-smooth surface of the apple, which is covered with printed text, is irresistible.

Maria G. Pisano’s O-livre twist, made from a children’s copy of Oliver Twist, pulped and used to make pages topped by a fragment of the book’s spine and held together by a bolt and wing nut.

“This is called an altered book, and it is actually made from a book,” says Garrison.

The collection, containing items predominantly from before the beginning of the 20th century, began its growth under the directorship of Charles Shaw, College librarian from 1927 to 1962, who started a collection of fine-press editions—books printed on a letterpress, with a focus on typography, using raised, inked, metal type.

The letterpress—invented in the mid-15th century by Johannes Gutenberg, a German printer and publisher—was widely used for printing books until the second half of the 20th century, when offset printing largely supplanted it. The role of the letterpress evolved toward serving the more handcrafted nature of artists’ books. The items in Shaw’s collection exemplify the long, rich history of private and fine presses.

As curator of the collection, whose reputation is widespread, Garrison enjoys interaction with researchers, teachers, and students from other Philadelphia-area colleges as well as with Swarthmore students.

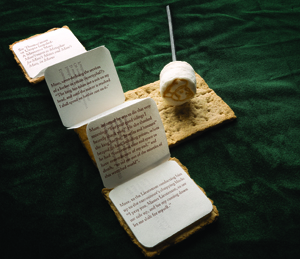

Angela Lorenz’s Sir Thomas’more or Utopia Impaled (2007) shows the ingredients used to make a s’more: Two Graham crackers made from yellow cloth unfold to reveal texts dedicated to More’s gallows humor and to the foul language for which he was known.

Faculty members and students from both the University of the Arts, which offers a master’s program in book arts, and the University of Pennsylvania, which offers a book-arts class, visit the McCabe collection.

“Even though they teach it, our collection is much stronger than theirs,” Garrison says. “I select material to show them, and they use it as inspiration or to get ideas, to study bindings, or obtain answers to graphics or typography questions.”

Swarthmore students can enjoy the collection by signing up for an annual spring-semester book-arts course offered by the College’s art department. Taught by Mary Phelan, an associate professor at the University of the Arts, the course includes a visit to the Rare Book Room to see examples of works by famous book artists.

Garrison is pleased that the collection draws art aficionados from outside the College and that it is becoming increasingly well-known further afield.

“Our book-arts collection has quite a reputation nationally,” she says, mentioning several positive comments she received from participants at a San Francisco conference she attended in February, “and my goal is to make it much more visible. Swarthmore is getting a name in the field of book arts. It’s awesome. How could you not love it?”

For more information on the College’s artists’ book collection, contact Anne Garrison at agarris1@swarthmore.edu or search the collection on Tripod, the library’s database.

Email This Page

Email This Page