Tragedy, Triumph, and a Boy’s Baseball Dreams

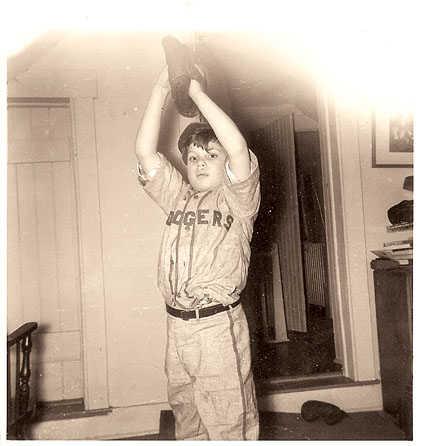

When I was a child in New York, my life—and, it seemed, my entire family’s life—revolved around the Brooklyn Dodgers. I had memorized the starting batting order, including their batting averages, which were updated every day in the newspaper. Each starting pitcher’s record and other statistics were easily recalled. I cut out articles, photos, box scores, and other minutiae from the newspapers and taped them to my wall. Each night, I slept in my Dodger uniform, to my mother’s great chagrin. But she shared my passion for the team and, in fact, may have fueled it even more than my father or older brother.

In summer, we rented a house in what was then rural northern New Jersey, where my days were filled with swimming, tennis, playing with my dog and—when he deigned to acknowledge my existence—baseball tosses and batting with my older brother, Peter Gessner ’61. But the soundtrack for all of these activities was broadcasts of Dodgers games on the radio. In those days, most games were played in the daytime and my mother, Doris Lindeman Gessner ’35, had arranged for a radio to be adapted for outdoor living by getting someone to exchange the regular power cord for a much longer one that was strung into the house through a window. Depending on how close the games were—and how engaging my own activities—I circled back near the radio at regular intervals. And, mother could always update me on the score and any highlights that I missed.

The height of this baseball fever in our household came in the early 1950s—a tremulous era for the Brooklyn Dodgers. This was a time of joys and tragedies for the teams that later became “the boys of summer” in Roger Kahn’s classic 1972 book of the same name. Brooklyn fans’ end-of-season disappointment was often assuaged by saying, “Wait ’til next year”—and after the famous (infamous to Dodger fans) 1951 playoff loss to the Giants, “next year” finally arrived with the delicious Brooklyn victory over the hated Yankees in 1955. But the sweetness of that first World Series triumph was shattered all too soon by the heartbreaking departure of the team for Los Angeles in 1958.

Living in Manhattan, it was curious that we were Dodgers fans at all. All my friends and relatives were Yankee fans, though there was the occasional odd Giant fan floating around. I think our affinity for Brooklyn had to do with my father’s identification with the underdog, the loser, and “dem Bums,” as we affectionately called the Dodgers, usually after a frustrating loss. (Only Dodger fans were allowed to use that phrase; never evil Yankee fans.) That was part of the attraction of the Dodgers—their contrast with the successful and triumphant perpetual winners up in Yankee Stadium. The Yanks, whose name alone suggested New England wealth and aristocracy, were decried by the comedian Joe E. Lewis, who famously declared, “Rooting for the Yankees is like rooting for U.S. Steel.” My liberal, academic father would have had a hard time rooting for U.S. Steel in those days, so rooting for “dem Bums” seemed more politically correct, long before that term had been invented.

A friend who lived in the Coney Island section of Brooklyn was a Yankee fan. When I first learned this about him, I remember being shocked at his lack of loyalty to his home borough. He explained that the Yankees were the winners, they were successful, and that was what he aspired to be. He wanted out of Brooklyn—a fast trip to Manhattan—and it was as if the Yankees were his ticket to ride.

Another powerful distinction between the Dodgers and the Yankees, at least in the early 1950s, was racial integration. Dodger great Jackie Robinson had broken the color bar in the big leagues in 1947, but it took the Yankees until 1955 to finally do the right thing. Even the Giants had acted much earlier by signing an African American in 1949. (The last major league team to integrate was the Boston Red Sox in 1959.)

When the Dodgers departed for the West Coast, I tried to continue rooting for them, but it just didn’t work. The New York Mets joined the National League in 1962, but they never really took the Dodgers’ place in my heart. I went through baseball withdrawal for a long time, until I finally settled in Chicago, where I could replay my childhood baseball rivalry.

Of course, I became a fan of the White Sox—the south-side, working-class team owned by an old Polish family (Comiskey). I learned to hate the Cubs—the lovably popular and wealthy north-side team owned by the patrician Wrigley family. During my years in Chicago, their rivalry was intense—reminiscent of that earlier Dodger-Yankee divide. You could not root for both teams. Each of the city’s two daily newspapers was clearly identified with one or the other. To a White Sox fan, a Cub loss was almost as good as a Sox win. (All across the country there are baseball fans who feel the same way about the Yankees—and love to see them lose.)

I returned to New York a few years ago and finally adopted the Mets as my team. My departure from Chicago preceded the 2005 White Sox World Series victory, so I missed out on that bit of excitement. My Yankee-hating has continued unabated as I also root for their arch rivals, the Red Sox. A particularly pleasurable day is when both the Mets and Red Sox win and the Yanks are defeated. To make it even sweeter, throw in a White Sox victory, a Cubs loss, and a Los Angeles Dodger win—but the latter doesn’t count much anymore although it still it provokes old and fond memories of a childhood loyalty to a beloved but heartbreaking team.

Stephen Gessner is an educational consultant living in Shelter Island, New York.

Email This Page

Email This Page