Jewels of Potential: Swarthmore students have benefited mightily from building benefactors

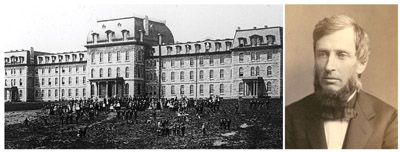

Trotter was originally known as the Science Hall. Built in 1882, with funds from Samuel Willets (pictured above), it was renamed in 1937, in honor of Spencer Trotter, professor of biology and geology.

A stroll across Swarthmore’s idyllic, 300-acre arboreal campus presents an ideal opportunity to meditate on generosity. Imagine the early 1850s, when the College was just a dream in the minds of a small group of Quakers. One of them—Edward Parrish—rode out on his horse from meeting to meeting across the mid-Atlantic region pitching the idea of a college to Hicksite Friends. He described it as a place where their sons and daughters could learn without being harassed for their pacifist views. Eventually, 2,000 “subscriptions” of $25 and more were purchased by the Quaker merchants and farmers, and that seed money built the building that became Swarthmore College. Edward Parrish went on to be elected Swarthmore’s first president. Today, that first building bears the name Parrish Hall.

When the fire of 1881 destroyed Parrish Hall, then-president Edward Magill raised money, once again through the sale of subscriptions. The College was able to rebuild and even pay off its $12,000 mortgage with the help of a $25,000 gift from Samuel Willets, Swarthmore College’s first major donor. “A check … signed upon his deathbed, completed the amount necessary to cover our loss by the great fire,” wrote Magill in Volume 1, Issue 1 of the Phoenix (so named after the fire). “The Alumni have also remembered their Alma Mater in her hour of need,” he added, by contributing $2,500 to rebuild the library collection.

Parrish has always been the heart of Swarthmore College. Around it sprouted new dormitories, classrooms, athletics facilities, libraries, arts and recreation facilities. Every one of those buildings—for that matter, every scholarship and every endowed chair—is rooted in a story of generosity. Some of Swarthmore’s benefactors chose to give anonymously, such as the donor of the decade-old Alice Paul residence hall. Others proudly put their names on their legacies. Eugene Lang ’38, the most generous donor in Swarthmore College’s history, built not only the Lang Music Building, but also the Lang Performing Arts Center and Lang Center for Civic and Social Responsibility, and endowed many chairs and scholarships.

First President Edward Parrish (bottom, right); his namesake building, circa early 1870s.

Many of the buildings on campus are named not for the donor but in someone else’s honor. Martin Laboratory, built in 1937, was named for Edward Martin, Class of 1878, who taught briefly at the College and served on its Board of Managers. A surgeon, he saved the life of Fred Kirby, founder of F.W. Woolworth five-and-dime stores. Kirby donated more than $1.8 million to the College—a huge sum in those days—and asked that the building be named for Martin.

Funds to build a gymnasium for women came from Mary Stevenson Wistar, who served as Swarthmore’s director of physical culture from 1893 to 1894. She was so dismayed at the lack of proper facilities for women that she returned to Swarthmore her year’s salary to start a fund for a gymnasium. (It was named Somerville Gym, after Mary Somerville, a famous 19th-century scientist.) Almost a century later, John and Marian Snyder Ware ’38 donated money to build Ware Pool. Marian was captain of the women’s swim team and wanted to give future students a chance to enjoy swimming as much as she did.

And today, treading in those early footsteps of Samuel Willetts and Fred Kirby, three of the College’s more recent donors have pledged their support for new, renovated, or repurposed buildings. In December 2012, Eugene Lang ’38 donated $50 million—the College’s largest gift ever—toward new engineering and science facilities. Two months later, Board Chairman Giles “Gil” Kemp ’72 and wife Barbara Guss Kemp gave $20 million to support key initiatives identified in the College’s 2011 Strategic Directions, including the renovation of Clothier Hall. In September, Quaker matchbox couple Salem Shuchman ’84 and Barbara Klock ’86 announced their lead gift for a $2.5-million challenge, matching every gift donated toward a new building that will support wellness, fitness, and theater. Currently under construction on the site of the former squash courts, the building’s name will be, appropriately, the Matchbox (see Page 9 for more details).

A residence hall that opened in 2004 was named for suffragist Alice Paul, Class of 1905. (For more on Paul, see Page 20.) The anonymous donor left the naming of the new dormitory to the students.

There are relatively few public displays of philanthropy on campus—few plaques on buildings, few visible markers to acknowledge the constant stream of generosity that created and continues to maintain and improve the College. You have to dig through yellowing files in the Friends Historical Library to learn about the people whose names grace the buildings.

Clothier, Wharton, Willets, Worth, Mertz, McCabe, Dana, Hallowell, Kohlberg, Lang, Clothier, Tarble, Kemp, Cornell, Sharples. This is the Swarthmore mantra falling from the lips of generations of students—those jewels of potential, the original raison d’être for Swarthmore. The buildings were a gift to them, to us, to learn, study, dream, invent, exercise, create, and flourish.

Today’s students are more diverse and international than those early Quakers could possibly have conceived. Yet, one hopes, they would be delighted to know that the seeds they generously sowed created a place of abundant intellectual inquiry, social engagement—and gratitude.

“People do so much at Swarthmore, but it’s less common to appreciate where we are,” says Jessica Schleider ’12, a former psychology major who, in 2009, helped to launch Gratitude Week on campus. “We can get caught up in the minutiae and forget to appreciate where we are right now.”

Email This Page

Email This Page