If You Seek His Monument, Just Look Around You

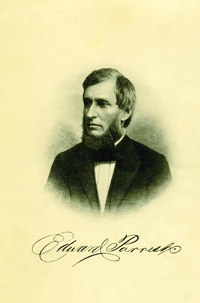

When the Board of Managers was created in December 1862, Edward Parrish’s name was at the top of the list. From the beginning, he had been part of the planning and the fundraising for the new college and, in 1865, was named Swarthmore’s first president.

list. From the beginning, he had been part of the planning and the fundraising for the new college and, in 1865, was named Swarthmore’s first president.

The College would not open for instruction until 1869, so Parrish’s initial years were spent planning, raising money, finding faculty, students, and whatever else needed to make Swarthmore a reality.

This was not his first foray into education. A pharmacist, he took an active role in the development of pharmacy education. He conducted a school in practical pharmacy for medical students at the University of Pennsylvania and later taught at the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy. He was president of the American Pharmaceutical Association, wrote scientific articles on pharmacy, and gave popular lectures on science at the Friends Social Lyceum and the Institute for Colored Youth in Philadelphia. He also wrote on the ethics of the profession of pharmacy, decrying the sale of suspect patent remedies by pharmacists.

The Parrish family also had a longstanding concern for abolition. His grandfather Isaac joined the Pennsylvania Abolition Society in the 1784, and his father Joseph and brother Dillwyn served long terms as presidents of the Abolition Society. Edward was involved in Abolition Society activities on behalf of African-American education. His niece Susan Parrish Wharton undertook settlement work in Philadelphia in the later 19th century and was largely responsible for bringing W.E.B. DuBois to Philadelphia to conduct his sociological study “The Philadelphia Negro.”

Susan Parrish Wharton and her mother, Susanna Dillwyn Wharton, Edward’s sister, would become founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in 1909. Edward served only one year as president after Swarthmore College opened in 1869, his exit probably occasioned by disagreements with the Board and other faculty on Parrish’s permissive attitude toward student discipline. He died in 1872 in what is now Oklahoma, where he had gone on behalf of the Religious Society of Friends to broker a peace among the Indian nations of the southern plains and between the tribes and the United States government.

At the laying of the cornerstone in 1866 of the building that would later be named Parrish Hall in recognition of his contributions, he expressed the thoughts of Swarthmore College’s founders: They expected a high grade of intellectual attainments from students and intended to create an institution “in which an education could be obtained equal to that of the best colleges in the land.”

Email This Page

Email This Page