Homage to the Past — Invitation to the Present

Craig Williamson creates a bridge across centuries with a new translation of Beowulf.

Professor of English Literature Craig Williamson was encouraged by members of a Lifelong Learning class to complete the translation of Beowulf that he had started years earlier.

Craig Williamson compares the act of translation to a kind of dance with a partner from a different world. Each partner’s rhythms and expectations are different, yet they share a sense of rhythm. Both possess a brain and legs, enabling them to process music, rhythm, and movement. And each dances a different dance, driven by common mental and physical impulses—a shared movement back and forth across a bridge between their worlds.

In August, Williamson published an acclaimed new translation of a work from a very different world—the Anglo-Saxon classic Beowulf and Other Old English Poems, released by the University of Pennsylvania Press.

Williamson loves language—his own and others. He writes poetry and is interested in the poetry of others. Now the Alfred H. and Peggi Bloom Professor of English Literature, he has taught at the College for 40 years.

In the mid-1960s, as a graduate student at Harvard, Williamson believed that modern English literature was his calling. Almost half a century later, he is a well-known scholar of medieval literature who regularly and happily transports himself back more than 1,000 years to Anglo-Saxon England, reading, teaching, translating, and even bringing to life in song and chants the works of Old English poets. [watch: Williamson sings Beowulf.]

So what steered Williamson from modern to medieval?

The answer is actually easier than most solutions to the Anglo-Saxon riddles on which he spends much of his time: Drafted in 1966 to fight in the Vietnam War, Williamson, a conscientious objector, went instead to Tanzania and performed alternate service with the American Friends Service Committee. There, he became fascinated by African literary traditions—the stories, proverbs, and riddles that were then just beginning to transition from oral to written forms—in Swahili and English in East Africa, and French in the West.

Williamson returned from Africa with a new research interest: the bridge between oral and written literature in his own language.

“This meant I had to go back to the Anglo-Saxons and the language they wrote in. It was my first contact with Old English,” he says, later amending this statement by adding that his introduction to Old English style and themes had actually occurred years earlier, when he read the works of J.R.R. Tolkien. Not merely a novelist but a scholar and teacher of Anglo-Saxon literature, Tolkien opened the door to Old English literature for Williamson, weaving into his Middle Earth novels numerous riddles whose intricacies resemble those of Old English riddle poems—and characters that smack of those in Beowulf.

“Back in the 1930s,” Williamson says, “Tolkien wrote one of the most important articles about Beowulf, revealing it as a valuable literary work—a combination of epic and elegiac poem—rather than a mere linguistic exercise.” Williamson dedicated his new edition of Beowulf to Tolkien, among others.

When Williamson began to translate Beowulf from Old English in 2006, he found the degree of difficulty so time-consuming that he almost abandoned the project after the first 200 lines. Fortunately for Anglo-Saxon scholarship, he didn’t—although he did leave it untouched for a while.

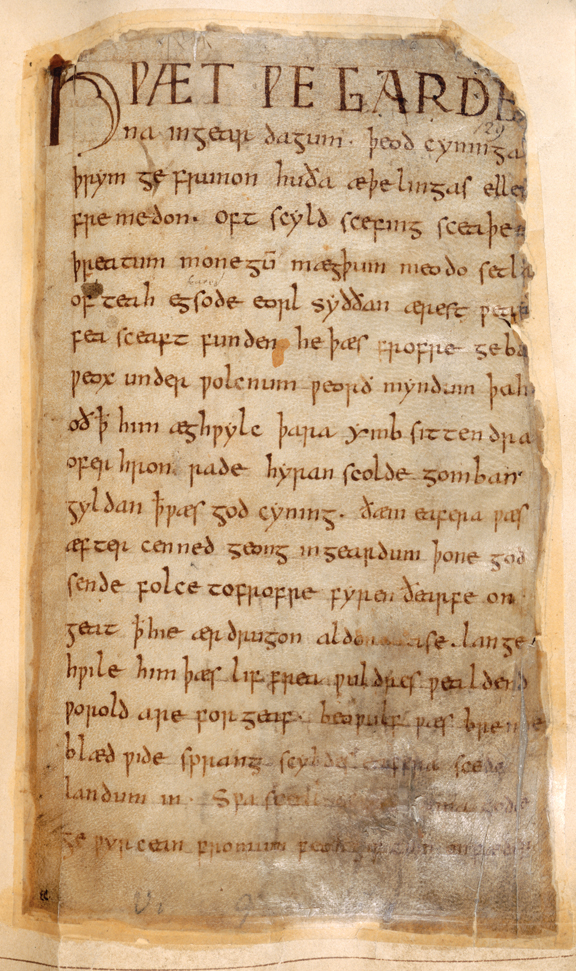

A fragment of the Beowulf poem from the British Library. Williamson reads Beowulf in his Chaucer and Medieval Literature seminars.

Not that Williamson wasn’t already an accomplished scholar and translator of Old English, the language spoken in England between ca. 500 and 1000 CE. After returning from Africa in the late 1960s, he again took up graduate research, this time at the University of Pennsylvania, where he worked on some of the Anglo-Saxon riddle-poems—riddles in the form of poems—preserved in a manuscript housed in Exeter Cathedral Library. This resulted in the 1977 publication of what is today considered the definitive edition of The Old English Riddles of ‘The Exeter Book.’ In 1982, Williamson’s translation and scholarly edition of all 90 extant Exeter riddles was published. Titled A Feast of Creatures: Anglo-Saxon Riddle-Songs, it was re-issued this year by the University of Pennsylvania Press.

But Beowulf—a book-length medieval poem of heroism, monsters, fratricide, power, treasure, and revenge—presented a more complex challenge. Estimated to have been written in the eighth century CE, Anglo-Saxon England’s best-known literary achievement challenges the translator with its complicated sentence structure, highly alliterative language, and densely packed imagery.

“Those first 200 lines took me almost a year, and since there are 3,182 lines in the poem, I reckoned it would take me about 15 years to finish it. So I kind of gave up on it,” Williamson says.

It took Swarthmore parent Thomas Koellhoffer (father of Jayne Koellhoffer ’07), who participated in Williamson’s 2007 Lifelong Learning course on the literature of J.R.R. Tolkien, to change the medievalist’s mind. An earlier Beowulf translation was one of several assigned readings for the course. Koellhoffer says he found Williamson’s command of Old English and Norse mythology impressive, particularly his animated and entertaining renderings of the poem in the original Old English. But, Koellhoffer adds, the accompanying translation was “somewhat ponderous and not so entertaining.” So when Williamson offered to read some passages from his own translation of the first 200 lines, Koellhoffer and his classmates were all ears.

“The entire class was awestruck by what we heard that night. When Craig finished his first reading, we erupted into spontaneous applause. His translation was accessible, engaging, and entertaining; it flowed beautifully and created pictures in the mind the way a good story is supposed to,” Koellhoffer says. When the reading ended, he flung the assigned Beowulf translation to the floor as a dramatic homage to Williamson’s prowess, the poetry of his words, and his infectious enthusiasm for his subject. The entire class encouraged their teacher to push on with his translation.

Williamson recalls: “The class members said to me, ‘You ask us to read a number of pages. Now, we ask you to read us a number of lines at each class.’ Although a little startled by the suggestion, he thought, ‘We have another five weeks in the course. I could give it a try.’”

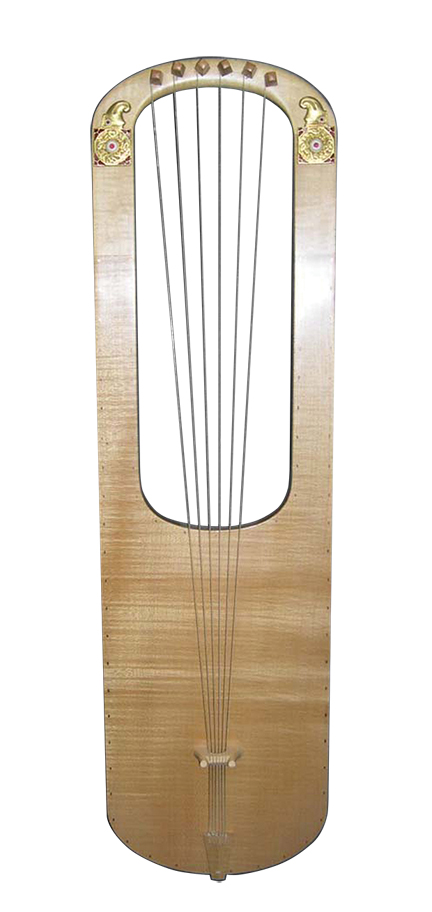

An eighth-century drawing of David composing the Psalms shows a lyre similar to what would have been played by minstrels performing Beowulf.

By the end of the five weeks, Williamson had completed another 200 lines, and he just kept going. “I’m really grateful to Tom and this class for urging me on,” he says.

The Beowulf translation took him five years. After completing all 3,182 lines, Williamson decided to include a number of additional poems in his new book—some related to Beowulf, others demonstrating different types of poetry, and some that he had wanted to read as an undergraduate. He introduces each poem with a brief essay. To ensure that the level and tone are appropriate for undergraduate and general readers, he also sought his students’ help.

“If there was something they didn’t understand, they asked me, and I made changes accordingly. Thanks are due to all my classes—young and old—for helping me find the right level for readers,” he says.

As for Koelhoffer, he remained a driving force: “My classmates and I continued to communicate with Craig about his progress long after the class ended,” he says. “And I bought a copy of the book as soon as it became available.”

The translator must know the language well enough to comprehend superficial and deeper meanings, “like the waters beneath the surface,” Williamson says, and combine both into a modern English that will reflect similar levels of meaning. “That’s difficult,” he says. “The more you’re able to read Old English and understand it without necessarily having to translate it in the life of your own mind, the closer you’re getting to going back in time and putting on the cloak of the Anglo-Saxon scop (poet or singer), to being there in the mead hall when the songs are being sung, to being a listener, possibly a singer in that fashion. Sometimes, it seemed as if I were channeling the voice of the Anglo-Saxon poet. Moving back and forth between my own English and the English of about 750 CE was like an intimate conversation between two poets, two languages, two cultures, carried on in a space that one critic calls ‘great time.’”

This lyre, which resembles the one in the drawing as well as another found in an Anglo-Saxon grave, was reconstructed for modern players by Messrs. Dolmetsch.

Williamson calls the translation an homage to the past and an invitation to the present. His students read Beowulf through the lens he has created, traveling back over the bridge of time that he has built. “It’s a thrill to see them reading the poem,” he says. “At the end of the poem, Beowulf’s body—his ‘bone-house’—lives on. The story has survived the passage of time and the transformations of telling for more than a thousand years. It will probably be recounted in some unimaginably beautiful and terrifying form after another thousand. I am pleased to be part of that endless retelling.”

Koellhoffer and his classmates may have been Williamson’s first and possibly most motivating reviewers, without whose encouragement the book might never have come to fruition, but they are by no means his only fans.

Senior Katharine Clark, an English literature and studio art major who read Beowulf as an assigned work for Williamson’s Senior Majors Colloquium, says: “Professor Williamson presents Beowulf in the context of other Anglo-Saxon poems, and his introductions make the English more accessible. His love for both the story and the language comes through, and that makes the poem come alive.”

And Benjamin Bagby, a performer of Beowulf and director of the medieval music ensemble Sequentia, who came to the College last year and delighted the campus community with a performance of Old English chanting, reviewed Williamson’s work: “These are renderings with bite and muscle, full of chewy sounds to delight any ear or voice, entering the mute reader’s eye and resounding within, at times filling a raucous hall, at times gently whispering into an interior fold of woe, of memory. In those resonant spaces, we hear again the scop’s voice.”

With the release of Beowulf, Williamson can lay claim to having translated and published a total of 6,000 lines of Anglo-Saxon verse. “I was kind of bereft when I was done,” he says. “I really didn’t want to be done.” So he got to thinking: “There are 30,000 lines extant of Old English poetry. Nobody has ever thought to translate them all, either into prose or poetry during the 150 years that this field of scholarship has existed. I’ve already translated 24,000 of them. It’s a fantastic project—making available every poem that every Anglo-Saxon poet ever wrote that we still have from beginning to end.” It will be about 1,500 pages, in several volumes.

Williamson is scheduled for a sabbatical next year. There’s little doubt as to how he’ll spend it.

Email This Page

Email This Page