Academic Nirvana

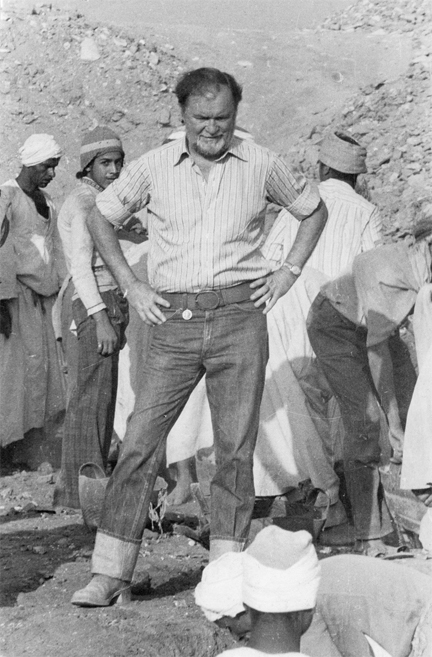

George Scanlon ’50 finds lifelong satisfaction and recognition in Islamic archaeology.

When George Scanlon first visited Egypt in 1948, he had no intention of becoming an archaeologist, much less spending the next 60 years of his life working there. Yet, for the past 35 years he has served as a professor of Islamic art and architecture at American University in Cairo (AUC) and is still going strong.

When George Scanlon first visited Egypt in 1948, he had no intention of becoming an archaeologist, much less spending the next 60 years of his life working there. Yet, for the past 35 years he has served as a professor of Islamic art and architecture at American University in Cairo (AUC) and is still going strong.

In 2009, he was the first non-Egyptian medieval archaeologist and scholar to be honored by the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA) in Egypt in recognition of his years of excavations in Nubia, an Egyptian region along the Nile, and Fustat, the first capital of Egypt under Arab rule, as well as for his publications related to these projects.

Thanks to Dean Everett Hunt, while still a Swarthmore student, Scanlon spent two years teaching at the Friends Boys School in Ramallah, on the West Bank, from where he visited Egypt.

“While I was in Ramallah and Jerusalem, which were very close at the time, I looked into the history of the area,” says Scanlon. “In Egypt, I did the same thing.” Those excursions sparked a lifelong interest in the Islamic world.

After graduating from the College with a degree in English literature and history, Scanlon served in the Navy during the Korean War.

Once discharged from the Navy, Scanlon pursued a master’s degree in oriental studies followed by a Ph.D., both at Princeton. His thesis on the Islamic “sciences of war” confirmed his determination to continue studying the Islamic world. He learned Arabic. While still a graduate student, Scanlon spent a year on the faculty of arts and sciences at the AUC. After returning to the United States to complete the Ph.D. in 1959, he went back to Cairo to direct the new American Research Center in Egypt (ARCE), which under his leadership became an important center of Islamic archaeology.

Scanlon’s work on excavation projects in Nubia and Fustat began in the 1960s, earning him recognition in the fields of Islamic art and art history. At an early excavation in Nubia, Scanlon and his colleagues unearthed fragments of Spanish lusterware and Chinese imports. “It was thrilling because we couldn’t have imagined finding both in one place,” he says. As a result of that dig, we determined that the technique of lustering had begun in Egypt about 100 years before the introduction of Islam in the seventh century and had come into its own in the Islamic period.”

At the same dig, he also found a collection of “torn-up bits of paper that you’d find in a wastepaper basket.” The fragments turned out to be early Islamic prayers—long Q’uranic quotations rolled up with amulets—which had more context than previous finds. “They dated to the 10th and 11th century, so we knew the Egyptians had a precursor to printing,” he says.

Scanlon also spent three seasons working in Nubia as part of the UNESCO campaign to salvage the archaeological sites threatened by the construction of the Aswan High Dam. As head of ARCE, Scanlon was approached by the director of the then–Egyptian Antiquities Service to assist with excavation and preservation efforts focusing on Islamic art and architecture in Fustat. “At that time, no foreigner had worked in the field of Islamic archaeology,” says Scanlon. “It had all been done through the Antiquities Service.” The first non-Egyptian to receive a concession to work in this field, Scanlon approached the task meticulously. “I applied the same kind of rigor that had been applied in Egyptology to Islamic and Coptic studies,” he explained.

Scanlon is still teaching and is currently researching a course on the pre-Islamic influences as they weigh on the buildings and objects produced after the triumph of the Arabic/Islamic conquest. Looking back, he says, “I’ve had years of academic nirvana.”

Email This Page

Email This Page