Andreas in 3-D

Manipulating the immutable is engineer/inventor/ceramicist’s motivating force.

Take a page out of his notebook. Any page. There will be drawings, you can be sure. And there will be words, printed in a neat, artistic hand. But while designs for a high-tech printer dominate the upper margins, the page’s bottom half features sketches of wood-kiln-fired clay tea cups modeled on millennial-old Japanese folk pottery. This spiral-bound notebook tracks the musings of the inventive mind of engineering major Andreas Bastian ’12 as he moves between two very different disciplines.

Take a page out of his notebook. Any page. There will be drawings, you can be sure. And there will be words, printed in a neat, artistic hand. But while designs for a high-tech printer dominate the upper margins, the page’s bottom half features sketches of wood-kiln-fired clay tea cups modeled on millennial-old Japanese folk pottery. This spiral-bound notebook tracks the musings of the inventive mind of engineering major Andreas Bastian ’12 as he moves between two very different disciplines.

“He’s always sketching something,” Matt Zucker, assistant professor of engineering, says of his spirited advisee. “He combines engineering with artistic creativity. It’s fun to look over his shoulder and see what’s going on in his notebook. Andy is a talented designer who has the ability to visualize structure and mechanics in 3-D. He’s particularly gifted at that.”

Bastian’s notebook is tangible evidence of two qualities Zucker ascribes to him: “creative and disciplined.”

Working out his ideas in the notebook, Bastian explores the dynamic between engineering, his major, and ceramics, his other passion.

Son of an astrophysicist father and a mother who kept a ceramics studio at their home in New Mexico, Bastian’s early memories reflect his current passions. While his father told him bedtime stories that featured charged-particle interactions, his mother taught him to draw and play with clay. They offered one mantra to their eldest son: “Do what makes you happy.”

“I love engineering for the problem solving, the understanding I gain, and my application of that knowledge,” Bastian says. “It’s an intellectual pursuit rather than an emotional one, which ceramics is for me. Ceramics is a collaboration with forces beyond your control, due to the unpredictability of the wood-firing process,” he says, his eyes lighting up. “I welcome surrendering control.”

The early-morning light streaming through the windows of Beardsley Hall’s third-floor ceramics studio has been Bastian’s boon companion since he began sneaking into the ceramics studio, trusty French press coffee pot by his side, his sophomore year. “I particularly liked working in the early morning because the studio was guaranteed to be completely deserted, which allows for uninterrupted focus,” he says.

“He understands that time is his friend, not his enemy but a resource,” says Syd Carpenter, professor of studio art and department chair. Carpenter, a ceramicist who has taught Bastian for three semesters, became aware of this early on, when she arrived in the studio at 7:45 a.m. to find he had been working well ahead of her—long enough to throw several pots.

Bastian is not the first engineering major Carpenter has seen in her classes. “Physics majors, too, are interested in the potter’s wheel. It’s an outlet for the visual part of their practice and a good marriage of the disciplines,” she explains.

“In the studio Andreas is one of a number of students doing outstanding work,” she adds. “He is a distinctive spark of ambition and imagination in this extraordinary group of makers. They’re glad he’s there, because he’s doing work on such a high level. He invents in the clay studio. I think, ‘How did he do that?’

“I call him amazing Andreas, because of his range and how he is able to make connections between multiple disciplines,” Carpenter continues. “This is what a college like this is for—for a mind like his to come here and make these connections between engineering, ceramics, design, folk art. He has the initiative to investigate not only the intellectual side but the tactile and practical side.”

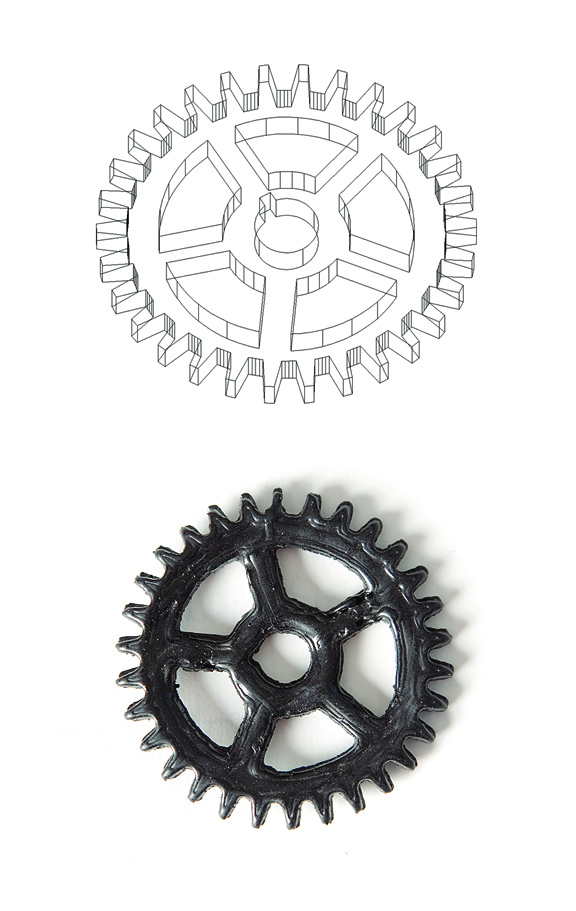

A CAD model of a gear (top) served as a test case for the 3-D printer built by Bastian. The wax version of the gear (bottom) was generated by the 3-D printer.

While Bastian discovered the ceramics studio his sophomore year, he also was learning about 3-D printing. According to Bastian, the technological advances promised by 3-D printing—the process of creating three-dimensional objects from a digital file using a materials printer—will change how many things are made.

“It’s like the invention of the cotton gin,” says Bastian, as he leans toward the 3-D printer he created and which operates in a lab in Hicks Hall. “It frees human capital for other things. Or the invention of the printing press. It killed the scribe industry, but people gained a lot of printing work. The same thing happens with 3-D printing. You still need someone to run the printer, make parts and materials.”

Almost anything can be created on 3-D printers, he explains. That includes food, jewelry, even prosthetic devices and artificial organs. Just this February, in Belgium, a 3-D printer used laser-fueled heat to melt metal powder in the shape of a jawbone; the exact replica was implanted in an elderly woman. “This is a whole new medium, an incredibly powerful tool for expression,” says Bastian, his words delivered rapid fire.

At Swarthmore, he says, interest in 3-D technology, which began garnering media attention in the early 2000s, is “starting to gain traction. A lot of my fellow engineering students were excited about 3-D printing, but a lot had never heard of it before coming here.”

The inspiration for designing his own 3-D printer struck “when I was sitting at McCabe [Library] working at the reserve desk.”

A grant from the Halpern Family Foundation Engineering Fund, established in 2007 by Michael Halpern ’68 and Christine Grant ’69, provided seed money for Bastian’s printer project. He worked on it last summer—sometimes for 90 hours a week—under the direction of Lynne Molter, engineering department chair, and Zucker, who provided a sounding board for Bastian’s design ideas.

“I’d say, ‘Show me something simpler—the KISS [Keep it simple, stupid] rule,” Zucker says. He also offered advice on the electronics and code part of the project. Trying to work out bugs meant, for Bastian, logging one 17-hour day, under highly caffeinated conditions, thanks to the French press.

“In the end, Andy found open-source software and made modifications to control his device,” Zucker says. “He picked up the technical know-how from the hobbyist 3-D printing community and was able to dig down and modify it for his own customized hardware.”

Bastian constructed a wax mold and cast a simple heat sink for his printer’s motor, making his project, he says, the first successful demonstration of an independently produced wax 3-D printer using selective laser sintering—a technique that uses a laser to fuse small objects into a 3-D shape. After he published his results on his website, a hobbyist wrote a story for Hackaday.com. From there, news spread through the blogosphere.

“It’s out there,” Zucker says of his student’s project. “People already are talking about it. It’s a pretty resounding success, though there are still some loose ends to tie up.”

Though Bastian has gained solid suggestions from fellow hobbyists online, he’s also traveled to New York City to connect informally with other 3-D aficionados. “I came back with ideas for my senior design project—and for the next prototype for this beast,” he says, gesturing toward the wood-and-plastic contraption.

His senior project involves processing plastic bottles into material to be used in an inexpensive 3-D printer that he assembled and is modifying.

While working out the kinks in that project early this spring, Bastian is contemplating his post-Swarthmore future. Plan A is getting his dream job—one that combines engineering and art—or spending a year doing ceramics.

As he sorts that out, Bastian’s mind turns to other matters. “Data visualization is one of my hobbies,” he says. Then there’s blacksmithing, molecular gastronomy, hunting wild mushrooms in the Crum Woods, and Ultimate Frisbee. And the logical next question is: How many interests do you have, Andreas?

“Too many.” He pauses. “A lot.”

Email This Page

Email This Page