Over 50? Welcome to the Age of Curiosity, Courage, and Passion

Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot ’66, The Third Chapter: Passion, Risk, and Adventure in the 25 Years After 50, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2009

The Third Chapter reminds me of conversations I have savored at Swarthmore. Like those, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot’s book invites new thinking about complex human issues, shares deep reflections about personal experience, invokes the findings of scholarly research, and applies intelligent analysis—all with graceful turns of phrase—concluding with a few suggestions on how to save the world.

The foundation of the book is a series of conversations the author shared with 40 individuals who are in the stage of life she calls the Third Chapter—the 25 Years After 50. Lawrence-Lightfoot spent two years traveling the United States, interviewing men and women in their 50s, 60s, and 70s who have entered this new life stage with curiosity, courage, and passion. Her book tells their stories, often in their own voices, offering interpretations of their experiences with reference to literature and developmental psychology as well as to sociological studies of aging and the life course. We hear the stories of individuals such as a corporate lawyer who becomes engaged with a community garden, a successful businesswoman whose Third Chapter takes her to Kosovo to work with children suffering the effects of war, a journalist and newspaper executive who begins to learn to play jazz piano at age 60, and the director of a major nonprofit who resigns to enter divinity school.

There are many reasons to recommend this book not only to readers who are in their own Third Chapter but also to those who are in earlier installments of their life stories. Lawrence-Lightfoot is correct that a stage of life between work and death is very new in human history. Adventuresome and creative individuals like those she interviewed are bringing to that new stage meanings that will shape the expectations and the experiences of all who will write their own Third Chapters in the future.

The author is a talented listener who draws from her interview partners not only accounts of their accomplishments but also of the journeys that preceded them. Like classic quest stories, these narratives recount fears, hesitations, obstacles, vulnerabilities, and ghosts from the past that must be recognized and overcome before the liberations and opportunities of a new life stage can be perceived and enjoyed. Among the greatest challenges described are the constraints that norms and stereotypes about aging place on living life to the full at any age. Lawrence-Lightfoot writes, “[this book] challenges the still-prevailing and anachronistic images of aging by documenting and revealing the ways in which the years between 50 and 75 may, in fact, be the most transformative and generative time in our lives….”

Even a book as abundant and rewarding as The Third Chapter cannot include everything without adding many more chapters of its own. We do not hear from individuals who are poor, or learn about the life course in other cultures, or see the ways that age peers in retirement communities may foster the creative adventures Lawrence-Lightfoot recounts. The author herself points out that the people she interviews all enjoy privileged status. They are comfortable (or more) economically and have both educational and occupational backgrounds that provide access to many resources and relationships that enhance their ability to take risks and be creative in a new stage of life. From my perspective as an anthropologist/gerontologist, I noted that although many of the individuals Lawrence-Lightfoot interviewed described their life transitions as “ethnographic” or “anthropological” excursions into unfamiliar territory, the author does not place her work in cross-cultural perspective. Doing this would not undermine her conclusions, but enhance them. The constraints of a strictly staged life course, with chronological markers at every sharply defined boundary, seem even more arbitrary if compared with cultures without these stages. From this point of view, the book title’s definition of Third Chapter as the “25 years after 50” is both a fitting reminder of American views about aging and somewhat at odds with the author’s admiration of individuals who have transcended chronologically defined expectations.

Lawrence-Lightfoot and the people she talks with focus mainly on individuals and the support they receive from significant people in their lives. Her reference to retirement communities contrasts the “segregation, isolation, and recreation” of early versions to the “yearning for lives of active engagement, purposefulness, and new learning” older people want now. My own research in retirement communities persuades me that they are very often the settings for just the kind of freedom from the constraint of age norms and opportunity for new learning that Lawrence-Lightfoot admires.

Like any good Swarthmorean, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot uses what she has learned as the basis for proposals about how to make the world a better place: We need to transform the parameters of our educational system to encompass lifelong learning and to reduce generational segregation. We need to innovate in the structure of work lives to increase opportunities for re-inventing ourselves, resting, and re-balancing work, love, family, community, and play. We need to open channels for the motivation and talent many Americans want to use in service to others during their Third Chapter.

Lawrence-Lightfoot’s book offers inspiration, guidance, and encouragement for fuller appreciation of the full lifespan to readers of any age.

—Jennie Keith

Centennial Professor Emerita of Anthropology and Provost Emerita

OTHER BOOKS, DVDs, and CDs

Carl Abbott ’66, How Cities Won the West, University of New Mexico Press, 2008. From the Gulf of Alaska to the Mississippi River and from the binational metropolis of San Diego-Tijuana to the Prairie Province capitals of Canada, the author explores the complex urban history of western Canada and the United States.

Dean Baker ’80, Plunder and Blunder: The Rise and Fall of the Bubble Economy, PoliPointPress, LLC, 2009. The author chronicles the growth and collapse of the stock and housing bubbles that he foresaw.

Jan (Burgess) Chozen Bays ’66, Mindful Eating: A Guide to Rediscovering a Healthy and Joyful Relationship With Food, Shambhala Publications Inc., 2009. This book offers suggestions on how focusing on the tastes, smells, thoughts, and feelings that arise at mealtimes can help people with eating disorders and other food issues. (CD included)

Jacqueline Carey ’77, It’s a Crime, Ballantine Books, 2008. This novel portrays the dire costs of today’s corporate culture of runaway greed in a fractured landscape filled with CEOs-turned-robber barons, privileged lives punctured by wretched excess, and personal relationships put to the ultimate test.

Peter Cohan ’79, You Can’t Order Change: Lessons From Jim McNerney’s Turnaround at Boeing, Portfolio, 2008. The author explores what sets the Boeing CEO apart from other CEOs.

William Cohen ’85, Embodied: Victorian Literature and the Senses, University of Minnesota Press, 2009. The author considers the meaning of sensory encounters in works by a variety of Victorian authors.

Kristin (Sims) Levine ’97, The Best Bad Luck I Ever Had, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 2009. In this historical novel, set in 1917 Alabama and inspired by the author’s family history, a friendship between a white farm boy and an African American city girl sends ripples through a rural town.

Theodor Nelson ’59, Geeks Bearing Gifts: How the Computer World Got This Way, Mindful Press, 2008. The inventor of “hypertext,” who anticipated and inspired the World Wide Web, takes a look at computer history in a series of short, punchy chapters.

Osha Neumann ’61, Up Against the Wall Motherf**cker, Seven Stories Press, 2008. The founding member of the ’60s anarchist group Motherfuckers, Neumann chronicles their activities, exploring the meaning of past rebellions for current rebels.

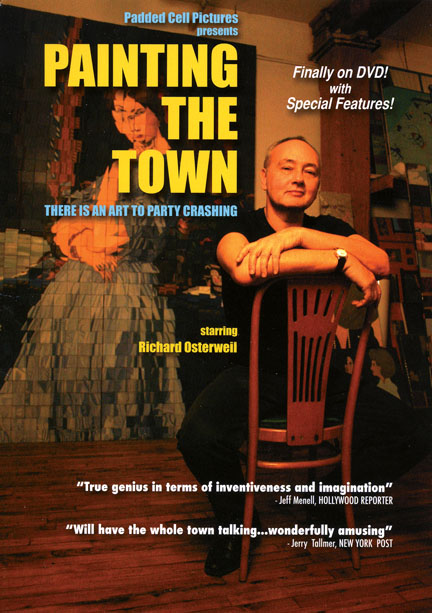

Richard Osterweil ’74 (star), Painting the Town: There is an Art to Party Crashing, Behar and Sackner, Padded Cell Pictures, 2008. The hit documentary features struggling painter, party-crasher, cabbie, and raconteur Osterweil, as he shares his outrageous efforts to experience how the other half lives.

Gillian Rogell ’68, At the Heart of Chamber Music: A Guide for the Player, the Coach—and the Music Lover, Musicalchemy, 2008. This first-of-its-kind chamber music DVD, featuring the Jupiter Quartet and Paul Katz, founding cellist of the Cleveland String Quartet, is aimed at helping young professional string players become good chamber music coaches.

Christine Shepardson ’94, Anti-Judaism and Christian Orthodoxy: Ephrem’s Hymns in Fourth-Century Syria, The Catholic University of America Press, 2008. This book investigates the anti-Jewish and anti-Judaizing rhetoric of Ephrem, a fourth-century poet and theologian from eastern Roman Syria.

Irene Silverblatt ’70 and Helene Silverblatt ’70 (co-editors and co-translators), Harvest of Blossoms: Poems From a Life Cut Short, by Selma Meerbaum-Eisinger, Northwestern University Press, 2008. A first English translation of these insightful poems brings to life a teenage Holocaust victim who moves readers with the riveting honesty and courage of her verses.

Amy Singer ’82, Charity in Islamic Societies, Cambridge University Press, 2008. The author demonstrates how historical circumstances, social status, gender, age, and other factors interacted with religious ideals to create a rich variety of charitable practices, from the beginnings of Islam to the present day.

Alexandra Michel and Stanton Wortham ’85, Bullish on Uncertainty: How Organizational Cultures Transform Participants, Cambridge University Press, 2009. This work shows how two successful investment banks trained their people and built their cultures in different ways, leading to strikingly different levels of success in today’s uncertain economic times.

Email This Page

Email This Page