Q&A with Professor of Religion Steven Hopkins

For his most recent work, Professor of Religion Steven Hopkins communed with the 14th century poet and philosopher Veṅkaṭanātha. But there’s no question about who takes top billing.

“I don’t even compare to this fellow in terms being a logician, a philosopher, a religious commentator, and also an incredible poet in three different South Indian languages,” says Hopkins, who also coordinates the Asian Studies program. “But in my own way, I’m trying to reflect both the work of a poet and the work of a scholar, in the same book.”

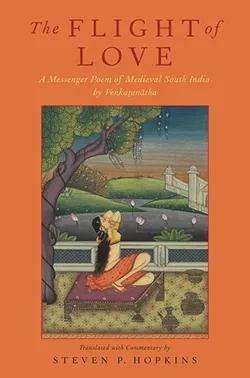

With The Flight of Love: A Messenger Poem of Medieval South India by Venkatanatha (2016, Oxford University Press), Hopkins combines philosophical scholarship with a deep dive into Sanskrit texts, in the tradition of South Asian literary scholarship.

It’s the third in a trilogy of books on this medieval South Indian saint-poet, after Singing the Body of God: The Hymns of Vedāntadeśika in Their South Indian Tradition and An Ornament for the Jewels: Love Poems for the Lord of Gods by Vedāntadeśika. The latter was awarded the 2010 South Asia Council of the Association of Asian Studies A.K. Ramanujan Book Prize for Translation.

“That was kind of a surprise to me, actually — a wonderful surprise,” says Hopkins, who briefly studied with Ramanujan, the late South Indian folklorist-linguist.

Hopkins recently answered questions about The Flight of Love, the challenges and joys of translating the work of a master poet-philosopher, and what he hopes that readers will take from his work.

How does this book differ from the first two of the trilogy?

The first was mostly discursive, a monograph, and the second mostly focused on translations of poems in three different languages composed in honor of the Hindu god Vishnu in a single South Indian temple shrine. This book focuses on a single Sanskrit poem, a “messenger poem” or sandeśa-kāvya, entirely in the mode of love that reads at times like a secular love poem. It’s like the Biblical Song of Songs in Sanskrit. The book combines verse translation with notes and a thematic commentary at the end, which is my own sort of contemporary take on things, where I also talk about the poem as interpreted by scholastic theologians in the poet-saint’s religious tradition from the 18th to the 20th centuries.

Which of its themes do you think will resonate with readers?

I’d say the connection between landscape and human emotion. Human bodies and love and the way nature, in a sense, mirrors our emotions, vivid South Indian themes. So the book is filled with this idea of the natural world as being alive, in an animate way, and also responding to human emotions. Also, the idea of nature as a living thing, very much inhabited by gods and demons and spirits — our bodies responding to the aliveness of nature, and nature responding to our bodies, our grief, joy, love and loss. Much of it is about lament and love-in-separation, universal things.

What was your biggest challenge in the translation process?

What I’ve tried to do in all my work is to really bring out the splendors of ancient South Indian languages into modern, contemporary English verse. For this book, what I’ve tried to do is both bring a compelling example of medieval lyrical Sanskrit to life and do the work of the scholar through the notes. So, in a way, it’s kind of two-fold, the poet is foregrounded, but there’s the scholar working in the background. In this way I like to mirror Veṅkaṭanātha himself, the poet-saint and philosopher. I really encourage the reader to appreciate the lyrical beauty and power of the Sanskrit through a vivid and rhythmic American English that is alive in the ear and in the eye on the page.

What do you love most about what you do?

It’s a precious and powerful thing to spend so many hours as a translator, communing with another voice from another time. And really trying to be loyal to that other voice, and at the same time creating poems in English. I think there’s a kind of ecstasy for me, an intellectual ecstasy, in communing on that level. But there’s also an alchemy, there’s a magic, when the English comes — it doesn’t replace the original, but it kind of moves alongside it, touching, caressing. For me translation is above all an act of love.